|

Farming

Techniques

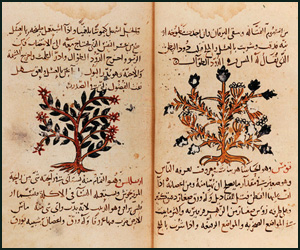

Muslim farmers

raised productivity mainly thanks to the introduction of higher

yielding new crops and better varieties of old crops, which made

possible more specialised land use, and more intensive rotation;

besides extending and improving irrigation, and spreading

cultivation into new or abandoned areas, and developing more

labour intensive techniques of farming.[1]

Again, old Eastern tradition, Yemeni

above all, is

responsible for improved soil management, `garden agriculture’,

which Glick notes, imposes the necessity of cultivating in such

a way as to preserve the maximum amount of moisture in the soil.[2]Which

hence adds the ecological dimension. Soil rehabilitation, Bolens

notes, was particularly cared for, and preserving the deep beds

of cropped land from erosion was `the golden rule of ecology,’

and was `subject to scrupulous laws.’[3]

Fertilisers were also used according to a well advanced

methodology;[4]soils

classified and enriched by various methods (other than by

fertiliser use), which included ploughing (normal and deep),

hoeing and digging.[5]The

rotation of crops, which in subsequent centuries was deemed a

crucial factor in the English agricultural revolution had a wide

practice, and together with new crops and better irrigation,

multiplied yields by three.[6]

This comes about through the joint knowledge of plants and

soils, the mastery of botanical and edaphic science.[7]Hence,

in Andalusia

,

well before the era of the English physiocrats of the 1800s,

Bolens says, this agricultural revolution was closely based on

high levels of knowledge of the life sciences and on a love of

nature which was the common gift of both the Islamic and the

Hebraic tradition.[8]

This

Islamic science

transferred straight to

its Christian successors. In Sicily

,

farming know how, in its wide variety, shows a direct Islamic

influence visible in the use of Arabic terminology. Notary acts

of the 14th-15th centuries related to

sugar farming and horticulture highlight the powerful Arabic

presence (in italic), terms such as catusu: Qadus (pipe

of cooked clay); Chaya: taya (hedge, or garden wall);

Fidenum: fideni (sugar cane field); Fiskia: fiskiya

(Reservoir); Margum: marja (inundated field); Noharia:

nuara (irrigated cottage garden); Sulfa: sulfa

(advance of credit granted to farmers); etc.[9]To

this day Malta and Gozo preserve such Islamic influence, the

more technical the jargon, the more purely Arabic the terms

become.[10]

The

Muslims alos brought new instruments that made it possible to

grow the new crops, which would otherwise have been impossible

with the typically classical agricultural methods.[11]And

this legacy is obvious in the technical jargon as well. To take

a glance at the philological correspondences alone, Serjeant

points out, -aretrum the plough is obviously related to

the Arabic root haratha, sulcus a furrow to the

word saliq, and iugum a yoke with ingerum

an acre (though less than an English acre) is evidently the same

word as South Arabian haig a yoke of oxen or, by

extension, an acre, the amount they can plough in a day.[12]

[1]

A. Watson

: Agricultural Innovation, op cit, pp 2-3.

[2]

T.F. Glick: Islamic

and Christian Spain; op cit; p. 75.

[3]

L. Bolens: Agriculture

, in Encyclopaedia (Selin ed), op cit,

pp. 20-2; at p. 22.

[4]

T. Glick: Islamic, op cit, p. 75.

[5]

Derived from A.M. Watson

: Agricultural, op cit, chapter 23.

[6]T.F.

Glick: Islamic and Christian Spain.

p. 78.

[7]

L. Bolens:

Agriculture

: in

Encyclopaedia (Selin ed); op cit;

p. 22:

[8]

Ibid.

[9]

H. Bresc: Les Jardins de Palerme; in Politique et

Societe; op cit; p. 81.

[10]

R. B. Serjeant: Agriculture

and

Horticulture; op cit; p. 536.

[11]

R.J. Forbes: Studies, op cit, p. 49.

[12]

R. B. Serjeant: Agriculture

and

Horticulture; op cit; p. 535. |