|

Introduction and Diffusion of New Crops

In the words of

Wickens, Spain received (apart from a legendary high culture),

and what she in turn transmitted to most of Europe, were all

manner of agricultural and fruit-growing processes, together

with a vast number of new plants, fruit and vegetables that we

all now take for granted.[1]

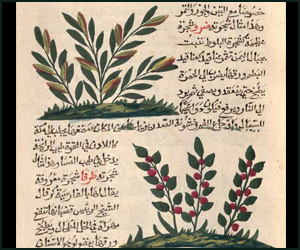

These new crops included sugar cane, rice, citrus fruit,

apricots, cotton, artichokes, aubergines, saffron... whilst

others, previously known, were developed further.[2]

To these can be added roses and peaches, strawberries, figs,

quinces, spinach, and asparagus, hemp, the mulberry and the silk

worm.[3]

Muslims also brought to that country rice, oranges, sugar

cane and cotton;[4]

sub-tropical crops such as bananas and sugar cane were grown on

the coastal parts of the country,[5]

many to be taken to the Spanish

colonies in the Americas

subsequently. Also owing to the Muslim influence, a silk

industry flourished, flax was cultivated and linen exported, and

esparto grass, which grew wild in the more arid parts, was

collected and turned into various types of articles.[6]

In Sicily

, Lowe holds, practically

all the distinguishing features of Sicilian husbandry were

introduced by the Muslims: citrus, cotton, carob, mulberry,

sugar cane, hemp, date palm, saffron... the list is endless.[7]

`It

would make a whole book, and not the least interesting,’ Carra

de Vaux

insists,

on the history of flowers, plants and

animals that had come from the Orient

, and which are used in agriculture, pharmacy, gardens, luxury

trade, and arts.'[8]

Carra de Vaux lists tulips (Turkish: tulpan,), hyacinths,

narcissi of Constantinople, Lilacs, jasmine of Arabia, and roses

of Shiraz and Ispahan; peaches of Persia, the prunes of Damascus

, and figs of Smyrne. Also listed are the sheep of `Barbary',

goats, Angora cats, Persian coqs; products used for dyeing.[9]

De Vaux then dwells on what he sees `one of the great glories'

of the Arab world: the pure blood Arab horse, stressing the Arab

care and expertise.[10]

Agents of such

diffusion were many and diverse. Muslim rulers, such as Abd

Errahman III (912-961), promoted the culture of the sugar cane,

rice, and the mulberry.[11]

The Yemeni

element, benefiting of

long learned know how and skills in their country of origin, as

they settled in Spain, brought with them their irrigation

techniques, laws and administration, and also new crops and

systems of more intensive land use.[12]

Watson

also speaks of thousands

of mostly unknown individuals from many levels of society who

moved plants over shorter or longer distances for many different

reasons. Whether `Great or humble, they unwillingly collaborated

in a vast undertaking that was to enlarge considerably the range

of useful plants available over a large part of the known world.

They also prepared the stage for still further migration of

these same plants in the early modern era.’[13]

Crucial to

such a diffusion was the frontier-less, unified land of Islam,

which allowed crops (rice, hard wheat, sugar-cane, watermelon,

spinach, lemons, citruses…) to be taken from India and Persia to

the Near East and North Africa, and to Europe. Many crops were

probably found on the Indian sub-continent, such as the province

of Sind, where the Muslims had a foot-hold.[14]

Oman may have been a halfway-house in which new plants were

acclimatised before being passed farther to the north and, of

course, further west.[15]

The eastern part of the Islamic world was thus `the gateway’

through which passed on their westward journey all the crops,

with the exception of the tropical ones, then across the

Maghreb, into Spain, and Sicily

,

and from one Mediterranean island to another.[16]

The

progress of a number of crops in their journey West can be

looked at. Chalots, first, which derive their name from Ascalon

(Cepa Ascalonia), and were imported during the crusades.[17]

Spinach was imported first to Spain, where it was largely

witnessed in the 11th century, from whence it was

diffused to the rest of Europe.[18]

It was one of the earliest such crops to be received into

Europe, but it did not appear until the 13th century when it

seems to have made rapid progress.[19]

Aubergines, which spread into Italy in the 14th

century, came from Muslim Spain.[20]Sorghum,

too, is mentioned in Italy by the late 12th and 13th

centuries, by which time it had arrived in the south of France.[21]

Sour oranges and lemons appear to have spread slowly

through parts of Italy and Spain in the 13th and 14th. Hard

wheat probably appeared in the 13th.[22]

The Romans had imported rice but had never grown it on a large

scale, and it was the Muslims who started growing it on

irrigated fields in Sicily

and Spain, whence it

came to the Pisan plain (1468) and Lombardy (1475).[23]

Other crops which the Muslims either introduced or intensified,

include the mulberry tree and saffron; the first was necessary

for silk worm husbandry and industry; the second, appreciated in

cooking, and also in the medical sciences.[24]

Greater

information on the passage of crops from Islam to Western

Christendom

,

and their impact on both farming and local manufacturing, can be

gleaned by looking at the particular instances of sugar and

cotton.

The

Muslims developed the cultivation of sugar on a large scale.[25]By

the 10thcentury sugar cane was cultivated all over

North Africa (as in other places east), from where, it crossed

into Spain.[26]There

it was cultivated and sugar produced according to all crafts of

the trade.[27]Then

the Muslims acclimated the crop in Sicily

.[28]The

name `massara’ which is given to sugar mills in Sicily is of

course of Arabic origin. Before the crusades, parts of the West,

thus, already had sugar production. Early in the crusades, the

Europeans took over regions where sugar was produced, such as

Tripoli, the first place where they came across the crop, and

where they enjoyed it with delight.[29]Other

Eastern regions where the crusaders came across the crop include

Tyre; Sidon; and Acre. William of Tyre speaks enthusiastically

of the great sugar plantations of Sur.[30]

When the Crusaders took possession of the country, they were

very careful to maintain production which brought them

considerable wealth, such as the Lord of Tyre, who enriched

himself thanks to his sugar plantations.[31]

The Syrians were great experts at refining the product through

an elaborate process to extract sugar.[32]The

Crusaders followed exactly the same processes and methods as the

Muslims, and adapted the same terminology in the manufacturing

process, using massara to describe their mills.[33]

At Tyre, this industry was so prosperous that Frederick II

asked for workers to be

sent to Palermo as the local Sicilians had lost the skills; the

request was made to the Marshall Ricardo Filangieri.[34]

At Acre itself, Muslim prisoners were used for the making of

sugar.[35]After

the fall of the Latin

states in the East, the

plantations and production of sugar were transferred to Cyprus.[36]The

land became covered with sugar cane plantations, especially

around Baffo and Limisso, under the direct control of the local

rulers themselves.[37]

The Cornaro, an illustrious Venetian family, possessed in the

Limisso region vast plantations, whilst the Knights of Rhodes

possessed vast farms on the Colossi lands.[38]Here,

again, it was Muslim craftsmen, Syrian specialists, who were

imported to Cyprus to advise on sugar production.[39]

Between the years 1400 and 1415, about 1,500 Muslims were

captured by the Cypriots from the Sultan of Egypt

;

the King of Cyprus refused to return these on the grounds that

they were essential for the cultivation of sugar cane.[40]

Muslim expertise also spread elsewhere. Marco Polo mentions

Egyptian technical consultants teaching their methods of sugar

refining to the Chinese

in the second half of

the 13th century.[41]

The

progress of cotton, Watson

observes, owes mainly to

the fact that wealthy people copied what had become the manner

of dress of many Egyptians.[42]

The fashion set by the rich was sufficiently widespread, and

hence the demand for cotton was great enough to induce some

landowners and peasants to experiment with its cultivation.[43]

Thus cotton moved from Egypt

farther west, across

North of Africa into Spain and to successive Mediterranean

islands.[44]

Manufacture of cotton was first introduced into Europe by the

Spanish

Muslims during the rule

of Abd Errahman III.[45]

One of the most valuable Spanish applications of cotton was in

the production of cotton paper.[46]

Xativa, as already noted, was the centre of the paper industry

in Spain. The adoption of cotton as a material for the

fabrication of this article of commerce is said to be due to

`the practical genius’ of the artisans of Xativa, who produced

great quantities of paper, much of which, in texture and finish

will compare not unfavourably with that obtained by the most

improved process of modern manufacture.[47]From

Spain, cotton manufacture spread across Europe between the 12th

to the 15th century as far as England

, particularly in the form of fustian, a cheap cotton cloth with

a linen warp, which derives its name from the Cairo

suburb of Fustat.[48]

The

dependency upon Islamic skills in these agro-industries is most

particularly obvious. Any loss of Muslim expertise in one part

of Western Christendom

drives the rulers to

urgently request for expertise from anywhere Muslims could be

found. Hence, in Sicily

,

following the upheavals that affected the island in the mid to

late 12th century,[49]

the skills of growing henna, indigo and refining sugar had

disappeared as Muslims took flight from the land they cultivated

and some left the island altogether. Frederick II

,

for instance, had to send to the Levant for `duos hominess qui

bene sciant facere zuccarum’ (two men who can manufacture

sugar).[50]

Similarly, in the Christian kingdom of Valencia

, it

seems that the farming of both cotton and sugar cane had

disappeared after conquest of the place from the Muslims in

1238, and following the dispersal of its Muslim population,

since Jaime II sent to Sicily for `duos sclavos sarracenos

quorum alter sit magistro cotonis et alter de cannamellis’ as

well as for the seeds of cotton and sugar cane.[51]

In Spain, the Muslims, until their expulsion in the early 17th

century, surely met the demands and needs of specialised crops,

and the effects suffered by Spanish

faming following such

expulsions are widely acknowledged.[52]

Understandably,

many crops (and techniques and skills associated with them),

that began their life in Europe, found their way to the European

colonies of Spain and Portugal

.

Silk production was taken from Grenada to Mexico by Hernan

Cortes, and was developed there by the Viceroy Antonio de

Mondoza, who himself came from Grenada.[53]

Many other sub-tropical crops such as bananas and sugar cane

grown on the coastal parts of Spain also found their way there.[54]

Pacey notes, that it was the organization of the sugar

plantations which was novel at this time, and both cultivation

methods and cane processing technology used by Europeans in

Madeira and later on the Caribbean islands had been acquired

from the Islamic world, and from Sicily

.[55]

Morocco

had an important sugar

industry during the 15th century, and the north

Moroccan

town of Ceuta was

invaded by the Portuguese in 1415, just a few years before the

colonization of Madeira began, and Morocco was probably one

source of information concerning sugar technology, such as cane

crushing mills.[56]The

plantations on Madeira proved to be highly lucrative, and

exports to Europe expanded fast. By 1493 there were eighty

`factory managers' responsible for sugar production on the

island.[57]

The Islamic direct

transfer of crops to Africa is enlightening in many respects.

The spread of Islam on the continent caused the converted to

begin to wear clothes-as religion enjoined, which in turn

stimulated the growth of cotton in many places to meet fast

rising demand.[58]It

was the Muslims who introduced sugar cane into Ethiopia, and who

made the East African island of Zanzibar famous for its high

quality sugar.[59]

Other crops were diffused by the Muslims on the continent in

medieval times as reported by both Muslim travellers and by the

Portuguese later in the 15thcentury.[60]

It is almost certain that in medieval times West Africa received

other than cotton and sugar cane, colocasia, bananas, plantains,

sour oranges and limes, Asiatic rice and varieties of sorghum,

which were all decisive in impact since the range of crops

previously available was extremely limited.[61]

Most of the crops were probably brought from the Maghrib over

the caravan routes which crossed the Sahara.[62]

There is also linguistic evidence pointing to a Muslim

introduction for a number of crops; the names of several of the

new crops in the languages of the interior of West Africa seem

to be derived from Arabic names.[63]

Mauny notes that before agriculture became established in this

region, gathering of wild fruit, leaves and roots were main

products for subsistence.[64]

Many of the indigenous crops also gave little nutrition

in relation to the amount of land or labour required.[65]The

transformation of modes of living following such transfers was,

thus, far reaching.

Finally, it is worth highlighting that the crops introduced by

the Muslims had major impact on the local economies to this very

day. It had been said, Sarton

,

insists, that the gardens and orchards of Spain were the best

part of her Islamic heritage,[66]whilst

Gabrieli notes that the crops which the Muslims introduced

remain up to the present day one of the foundations of the

Sicilian economy.[67]The

new plants also created many changes in consumption and land

use.[68]

These plants became

the sources of new fibres, foods, condiments, beverages,

medicines, narcotics, poisons, dyes, perfumes, cosmetics, and

fodder as well as ornamental objects.[69]

[1]

G.M. Wickens: What the West borrowed; op cit; at p. 125.

[2]

M. Watt: The

Influence; op cit pp 22-23.

[3]

F.B. Artz: The Mind; op cit; pp 149-50.

[4]

A. Pacey:

Technology

, op cit

p. 15.

[5]

E. Levi

Provencal: Histoire de

l'Espagne Musulmane;

op cit; p.283.

[6]

W. Montgomery Watt: The Influence, op cit, pp 22-3.

[7]

A. Lowe: The Barrier and the Bridge, Published by

G. Bles, London, 1972; p. 78.

[8]

Baron Carra de Vaux

: Les Penseurs de

l'Islam, op cit; vol 2,

at p. 306.

[9]

Ibid. pp 309-19.

[10]

Ibid. pp. 329-36.

[11]

J.W. Draper:

History; op cit; Vol II; p.386.

[12]

T. Glick: Irrigation. In A.

Watson

: Agricultural Innovation; op cit; p. 80

[13]

A.M. Watson

: Agricultural innovation; op cit; p.89-90.

[14]

Ibid. p.79-80.

[15]

Ibid.

[16]

Ibid. p.80.

[17]

J. Andre: l’Alimentation et la Cuisine a Rome;

Paris; 1961; p. 20.

[18]

M. Rodinson: Les Influences de la Civilisation Musulmane

sur la Civilisation Europeene Medievale dans le Domaine

de la Consommation et de la Distraction: l’Alimentation;

in Convegno Internationale: op cit;

pp. 479-99.

p.484.

[19]

Crescentiis bk vi 55; 103 in A. Watson

: agricultural; op cit;

pp. 81-3.

[20]

D. Bois: Les Plantes almentaires chez tous les peoples

et a travers les ages; vol1; Paris; p. 355.

[21]

Crescentis bk iii 7; V.Niccoli: Saggio storico; Turin;

1902; p. 189; J.J Hemardinquer: l’Introduction du Mais;

1963; pp. 450-1 in A.M.Watson

: Agricultural; op cit; p. 81-83

[22]G.

Alessio: Storia linguistica; 1958-9; pp. 263-5; M. Gual

Camarena:

Vocabulario del commercio medieval; Tarragona; 1968; p.

422; in A. Watson

: Agricultural; op cit;

pp 81-3.

[23]

R.J. Forbes: Studies, op cit, p. 49.

[24]

P.Guichard: Mise en valeur; op cit; p. 178.

[25]

W. Heyd: Histoire; op cit; p.684

[26]

R.Dozy: Le Calendrier de Cordoue de l’Annee 961;

Leyden; 1873; p. 25; 41; 91.

[27]

Ibn al-Awwam: Livre de l’Agriculture

; Trad Clement Mullet; Paris 1864.

I; 365 and ff; and preface; p. 26.

[28]

M. Amari: Storia dei Musulmani in Sicilia; op

cit; II; p. 445.

[29]

Alb. D’Aix; ed Bongars; p. 270. in W. Heyd: Histoire du

commerce; op cit; p.685.

[30]

Historia, XIII, 3; in medieval French translation in

Paulin Pari’s edit., vol I, p. 480. The Sur of William

of Tyre is Tyre. See also E. Dreesbach:

Der Orient

;

(Dissertation); Breslau; 1901; pp. 24-8.

[31]

Burchard in

W.Heyd: Histoire; op cit; p. 686.

[32]

Alb. D’Aix; ed Bongars; p. 270.

Jacques de Vitry; p. 1075; 1099. in W. Heyd: Histoire du

commerce; op cit; p.685.

[33]

Taf and Thom., II; p. 368; Strehkle, in W.Heyd:

Histoire;

p. 686.

[34]

Huillard-Breholles, Hist.Dipl. Friderici II; Vol 5; pars

1; p.574. in W.Heyd: Histoire; p. 686.

[35]

Michelant-Reinaud: Bibliotheque des Croisades;

IV; p. 126 in W. Heyd: Histoire; op cit; p. 686.

[36]

See Herquet: Konigsgetalten des hauses Lusignan;

Halle; 1881; pp 165-70.

[37]

Sanuto Diari; X; 106; Mas latrie: III; 27; 88 in W.Heyd:

Histoire; op cit;

p. 687.

[38]

Ibid.

[39]

E. Ashtor; 1981:

105 in J.L. Abu-Lughod: Before European Hegemony.p.246.

[40]

A. Watson

: Agricultural; op cit;

Note 20; p. 211.

[41]

J.L. Abu-Lughod:

Before European Hegemony.p.246.

[42]

A.M. Watson

: Agricultural innovation; op cit; p.102.

[43]

Ibid.

[44]

Ibid.

[45]

J.W. Draper:

History; op cit; Vol II; p.386.

[46]

Ibid.

[47]

S.P .Scott: History; op cit; vol ii;

P. 387.

[48]

T.K

Derry and T.I Williams: A Short History; op cit; P. 98.

[49]

See N. Daniel: The Arabs

; op cit; pp. 148 fwd; for the relentless depredations

suffered by the Muslims, and their forced emigration

from their lands and farms.

[50]

Historia diplomatica v 573; 575 in A. Watson

: Agricultural; op cit; Note 2; p. 185.

[51]

J.E. Martinez Ferrandon: Jaime II de Aragon; 2

vols; Barcelona

; 1948.

Vol II; pp. 19-20.

[52]

See for instance, H.C. Lea: The Moriscos of Spain;

Burt Franklin; New York; 1968 reprint; p.379; S.P.

Scott: History; op cit; vol 3; p. 320; S. Lane-Poole:

The Moors in Spain; Fisher Unwin; London; 1888.

pp.279-80.

[53]R

de Zayas: Les Morisques et le Racisme d'Etat; Les

Voies du Sud; Paris, 1992.

p.200.

[54]

E. Levi Provencal: Histoire, op cit, p.283.

[55]

A. Pacey:

Technology

in world

Civilization, op cit; p.100.

[56]

Ibid.

[57]

Ibid.

[58]

V. Monteil: Le Cotton chez les Noirs, in Bulletin du

Comite d’Etudes Historiques et Scientifiques de l’A.O.F.

IX (1926); pp. 585-684;

R.Mauny: Notes historiques autour des principales

plantes cultivess en Afrique occidendate; in Bulletin

de l’Institut Francais d’Afrique Noire; Xv (1953);

pp. 684-730;

pp. 698 ff.

[59]

A. Pacey: Technology

, op cit, p. 15.

[60]

A. Watson

: Agricultural; op cit; p. 81.

[61]

Ibid.

[62]

Ibid. p.82.

[63]

J.M. Dalziel: The Useful Plants of West Tropical

Africa; London; 1948; pp. 122; 305-6 etc.

[64]

R. Mauny: Tableau geographique de l’Ouest Africain au

Moyen Age; Dakar; 1961; pp. 228-33.

[65]

A.M. Watson

: Agricultural Innovation; op cit; pp 81-2.

[66]

G. Sarton

: The Appreciation; op cit;

p.131.

[67]

F. Gabrieli: Islam in the Mediterranean World; in The

Legacy of Islam: 2nd ed. Ed J. Schacht with C.E.

Bosworth. Oxford Clarendon Press, 1974. pp 63-104, at P.

76.

[68]

M. W. Dols: Herbs; in Dictionary of Middle Ages; op cit;

vol 6; pp. 184-7;

p. 186.

[69]

Ibid. at pp. 185-6. |