|

New Forms of Land Exploitation

Islam,

Watson

points out, freed the

countryside from many arrangements which were `economically

retrograde.’[1]

Equally, Lowe observes that Muslim rule in Sicily

was an improvement over

that of Byzantium

as the latifondi were

divided among freed serfs, and small holders, and agriculture

received the greatest impetus it had ever known.[2]

Thanks to a Muslim custom, uncultivated land became the property

of whoever first broke it, thus encouraging cultivation at the

expense of grazing.[3]

New modes of production brought more agricultural land and

labour, as well as their product, into the market place, and the

forces of competition thus released were intensified by laws

rewarding innovators.[4]

Immamudin quotes from the documents of the School of Arabic

Studies in Madrid the type of contract entered into by

cultivators and landlords for the bringing of waste land (what

would in Arabic be called mawat) under cultivation.[5]Immamudin

also cites examples of share cropping contracts (one would call

these muzara’ah, musaqah, etc. in Arabic) that bear close

resemblance to examples given in the standard Arabic law-books,

and such forms of contract as those studied by Serjeant, and

which too are applicable today.[6]

This

highlights the advanced Islamic conditions in comparison with

Europe, where, England

excepted, only began to

abolish the feudal system late in the 18th century.

The Muslim tax system contributed to such and other

improvements; low rates of taxation helped keep alive a class of

smaller, independent landowners and a relatively prosperous

peasantry.[7]

Prior to Islam, taxes crippled both effort and innovation,

pushing the tendency for large estates to dominate the

countryside and for the peasantry to be enserfed.

The

Muslims also introduced a legal corpus in irrigation to protect

individual rights, and applied lower rate of taxation for land

watered by the Noria than by hand, leading to the prevalence of

small holdings of share-croppers and free farmers, as opposed to

the latifundia of antiquity with their scores of slaves.[8]

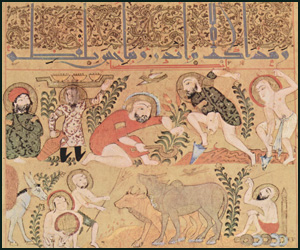

Experimental Farming and Botanical Gardens

It has been seen

above how Muslims managed to bring in new crops, adapt them and

diffuse them. They were able to do so mainly thanks to

experimental botanical

gardens. These were often in the charge of leading scientists

such as Ibn Bassal (fl 11th century) and Ibn Wafid

(b. 997-d. ca 1074). These

gardens, according to Watson

, were places `where business was mixed with pleasure, science

with art.’[9]And

these urges acted as strong stimuli for he adaptation of crops

from one place into another.

Abd Errahman I (rule began in 756), who was fond of flowers and

fruits, planted a beautiful garden in imitation of the Rusafah

Villa of Damascus

, a

summer country residence between Palmyra and the Euphrates

valley where he had lived for long with his grand father Hisham.[10]

Gradually, experimental gardens became part of a network which

linked together the agricultural and botanical activities of

distant regions, and so played a role of great importance in the

diffusion of useful plants. Only many centuries later did Europe

possess similar botanical gardens which acted as the same kind

of medium for plant diffusion.[11]

The earliest botanical gardens in Europe appear to have been

planted by Matthaeus Sylvaticus in Salerno

(c.1310) and by

Gualterius in Venice

(c.1330); other places

followed centuries later; Pisa

: in

1543; Padua, Parma and Florence in 1545; Bologna in 1568; Leyden

in 1577; Leipzig in 1580; Konigsberg in 1581; Paris (le Jardin

Royal du Louvre) in 1590; Oxford in 1621 etc.[12]

[1]

A. Watson

; Agricultural innovation, p. 115.

[2]

A.

Lowe: The Barrier; op cit; p. 78.

[3]

Ibid.

[4]

A. Watson

; Agricultural Innovation,

op cit; p. 115.

[5]

In R. B. Serjeant: Agriculture

and

Horticulture; op cit; p. 541.

[6]

Ibid.

[7]

A. Watson

: Agricultural innovation, p. 115.

[8]

Ibid. chapter 21; pp 114-6.

[9]

Ibid. chap 22.

[10]

S.M. Imamuddin: Muslim Spain; Leiden; E. J.

Brill; 1981. p.85.

[11]

A. Watson

: Agricultural innovation, op cit, chap 22.

[12]

See: A. Chiarugi: Le date di fondazione dei primi orti

botanici del mondo,’ Nuovo giornale botanico italiano

new ser. LX (1953) 785-839; A.W. Hill

: The History and function of botanical gardens;

Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden; II (1915)

185-240; 195 fwd; F. Philippi: Los jardines botanicos.

Santiago de Chile; 1878; etc. |