Farming

|

On the Muslim role in agricultural

development, Cherbonneau holds:

`it

is admitted with difficulty that a nation in majority of nomads

could have had known any form of agricultural techniques other

than sowing wheat and barley. The misconceptions come from the

rarity of works on the subject… If we took the bother to open up

and consult the old manuscripts, so many views will be changed,

so many prejudices will be destroyed.’[1]

So

many prejudices, which can be easily found with many authors

such as Ashtor who says:

`The

numerous accounts of these activities do not point to

technological innovations within the irrigation system, which

the Muslim rulers had simply taken over from their predecessors.

The records in the writings of the Arabic historians show that

those who drained the swamps and dug the canals were the

Nabateans, not Arabs

.’

[2]

`The information which

the Arabic authors provide us in the methods of agricultural

work, besides the irrigation canals and engines, is rather

scanty. But collecting these records from various sources one is

inclined to conclude that the Arabs

did not improve the

methods of agricultural work. There is only slight evidence of

technological innovations in near eastern agriculture throughout

the Middle Ages, whereas the history of European agriculture is

the story of great changes and technological achievements.’[3]

This picture of

inept Muslim farmers, shared by the overwhelming majority of

historians is contradicted by historical evidence. In fact, an

Islamic agricultural revolution preceded its European

counterpart by at least six centuries, Muslims pioneering in

many areas that were later on to be identified with the European

agricultural revolution.[4]It

was also from Islam that many such pioneering elements were to

transfer to Western Christendom

as will be amply shown

in this section.

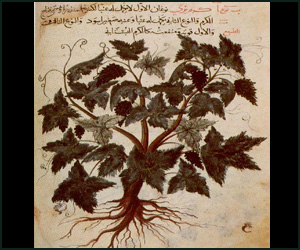

Before looking at such

impacts, it is worth making a brief outline of Islamic early

accomplishments in farming. Artz tells us that the great Islamic

cities of the Near East, North Africa, and Spain were all

supported by an elaborate agricultural system that included

extensive irrigation and an expert knowledge of agricultural

methods, which were the most advanced in the world.[5]

The Muslims knew how to fight insect pests, how to use

fertilizers, and they were experts at grafting trees and

crossing plants to produce new varieties, and by these means

areas that have since become lands of low agricultural

production were able, in early Islam to support huge

populations.[6]

Cereal yields in Egypt

according to Von Sivers

were around 10 for 1, yields, which will only be obtained in

Europe at the end of the 17th century.[7]

In Muslim Spain, such was the quality of product some wheat

could keep for a century in adequate storage conditions.[8]

In Sicily

,

agriculture remained in Muslim hands

under Norman rule, and was, according to Scott `carried

to the highest perfection.’[9]

There, every plant or tree, whose culture was known to be

profitable and which could adapt itself was to be found in the

gardens and plantations; records were kept of the crops produced

in each district; the methods of their disposition and the

prices they brought were noted on the public registers; the

breeds of horses, asses, and cattle were improved; and the

greatest care was taken of them; and food, which after

experiment was found to be the most nutritious, was adopted.[10]

Bolens, thus, concludes that Islamic

farming represented: `a culmination of a unique balance derived

from a deep love for nature… a relaxed way of life, ecological

balance, and the acquisition of knowledge of many `civilized

traditions.'[11]

Gardens

and gardening, for

pleasure, experimentation, or as subsidiary economic outlet,

used to form an integral part of Islamic life.

In Algiers, a visitor once

counted 20,000 gardens, and all around the city grew all sorts

of fruit trees; great varieties of flowers, and all sorts of

plants; fountains abounded, and in these gardens, on the lush

greenery, families used to come and find enjoyment and solace.[12]

In Spain, writers speak endlessly of the gardens and lieux de

plaisance of Seville

, Cordova and Valencia

, the last of which was called by one of them ``the scent bottle

of al-Andalus.’[13]

Market gardens, olive groves, and fruit orchards made some areas

of Spain—notably around Cordova, Granada, and Valencia—"garden

spots of the world." The Island of Majorca, won by the Muslims

in the 8th century, became under their husbandry `a

paradise of fruits and flowers, dominated by the date palm that

later gave its name to the capital.’[14]

The picture

that emerges, according to Watson

, is

that of `a large unified region which for three or four

centuries, and in places still longer, was unusually receptive

to all that was new,’[15]

and also was `unusually able to diffuse novelties;’ and more

crucially: `both to effect the initial transfer which introduced

an element into a region and to carry out the secondary

diffusion which changed rarities into commonplaces.’[16]To

accomplish this, attitudes, social structures, institutions, the

economy, infrastructure, science all played their part; and not

only in farming, but also in other spheres of the economy, and

outside the economy; all `touched by this capacity to absorb and

to transmit.’[17]

How Islamic civilisation diffused all such green science to the Christian West is what focus is on here

[1]

A. Cherbonneau:

Kitab al-Filaha of Abu Khayr al-Ichbili, in

Bulletin d’Etudes

Arabes, pp 130-44; at p. 130.

[2]

E. Ashtor: A Social; op cit; p. 46.

[3]

Ibid. p. 49.

[4]For

accounts on the Muslim agricultural revolution, see for

instance:

-A.M. Watson

: Agricultural Innovation in the Early Islamic World;

Cambridge University Press; 1983.

-A.M. Watson

: `The Arab Agricultural revolution and its diffusion,'

The Journal of Economic History 34 (1974): pp. 8-35.

-T. Fahd: Botany

and Agriculture

, in the Encyclopaedia (Rashed ed) pp 813-52.

[5]

F.B. Artz: The Mind;

op cit; pp. 149-50.

[6]

Ibid.

[7]

In P.Guichard: Mise en valeur du sol et production: De

la `revolution agricole’aux difficultes du bas Moyen

Age; In

Etats et Societes (J.C. Garcin et al edition); Vol

2; Presses Universitaires de France; p.2000; pp. 175-99;

at p. 184.

[8]

E. Levi Provencal: Histoire de l'Espagne Musulmane;

Vol III; Paris, Maisonneuve, 1953. p. 272.

[9]

S.P. Scott: History; op cit;

vol 3; p. 42.

[10]

Ibid.

[11]

L. Bolens: `Agriculture

’ in Encyclopaedia (H Selin ed); op cit;

pp 20-2, p. 22.

[12]

In G.Marcais: Les Jardins de l’Islam; in Melanges

d’Histoire et d’Archeologie de l’Occident Musulman;

2 Vols; Alger; 1957; pp 233-44; p. 241.

[13]

H. Peres: La Poesie Andaluse en Arabe Classique au

Xiem siecle; Paris; 1953; pp. 115ff.

[14]

W. Durant: The Age of faith; op cit; p. 298.

[15]

A. Watson

: Agricultural innovation, op cit, p.2

[16]

Ibid.

[17]

Ibid.

|