Impact on the West

Modern medicine is very close to Islamic medicine due to the

early transfers of Muslim medicine to the Christian West.[1]

Jacquart’s summarises the main translations of Islamic medical

works.[2]

The pioneer of such translations was

The

Islamic influence persisted in medicine as in other sciences for

the subsequent centuries, and this despite the humanists and

Classical inspired Renaissance writers, who rose in rebellion

against such Islamic influence, as will be examined in the final

part of this work, and as Whitty remarkably outlines.[9]

Specialist texts were heavily influenced by Islamic

writers-diagnosis from urine, or ocular surgery would be

examples.[10]

Islamic medicine made few contributions in relation to

particular new diseases like syphilis, or the new surgical

problem of dealing with gunshot wounds, but overall, the

majority of people in

A

major problem relating to this issue of transfer concerns the

assertion found amongst mainstream historians that the

translations from Arabic in the 12th century aimed at

the recovery of the Greek-Ancient learning. This is a gross

fallacy. The medieval Western translators, who were behind the

rise and renaissance of Western Christendom, and the authors of

the largest translation effort in history, from Arabic into

Latin

, in

the 12th-early 13th century, were not

interested in the Greek-Ancient material but in Muslim learning.

Whether Adelard of Bath, who talked of his Arab masters,[13]

or Daniel of Morley who compared Paris’ scholars to asses, and

who rushed back to Toledo

in Spain to dwell

amongst ‘Arab’ books,’[14]

or Gerard of Cremona who pitied the Latin for the poverty of

their learning compared to the Muslims,[15]

or Robert of Ketton, who speaks of ‘ the depths of the treasures

of the Arabs,’[16]

all sought Islamic learning. They thought very little of Ancient

learning. Raymond of Marseilles, for instance, in 1140, says

‘that students of astronomy were compelled to have recourse to

worthless writings going under the name of Ptolemy and therefore

blindly followed; that the heavens were never examined, and that

any phenomena not agreeing with such books were simply denied.’[17]

The same attitude was held in regard to medicine. Stephen of

Antioch who translated the Liber Regalis of Al-Madjusi,

even learned Arabic in order to advance from "the naked

beginnings of philosophy," and he proposed, if the favour of God

should permit, to go on from his study of the things of the body

to "things far higher, extending to the excellence of the soul,"

more specifically, "more famous things which the Arabic language

contains, the hidden secrets of philosophy."[18]

Perhaps he was thinking of works by Ibn Sina

, to

which his medical interests might have led him.[19]

For Stephen and for most of the translators from Arabic the idea

of Greek sources at this date was secondary, and the impact of

Just

as the intentions of the medieval scholars have been

misrepresented by modern historians, medieval and later Islamic

breakthroughs have also been misrepresented by these same

historians through wrong attributions. Vaccination, for

instance, wrongly attributed to Jenner (1749-1823). The method

of vaccination was known to the Ottoman Turks

long before Jenner,

under the name of Ashi (engrafting), which they had

inherited from old Turkic tribes; the nomads used to inoculating

their children with cowpox taken from the breast of cattle. This

kind of vaccination and other forms of variolation were

introduced into

A

similar problem of misattribution relates to the matter of

pulmonary circulation.

The Syrian medical scholar Ibn Al-Nafis (1210-1288)

described it in his Sharh al-Qanun, a Ms. which can be

found in a number of examples in

‘This was Galen's theory. It persisted unchanged and

unchallenged down to the Renaissance (by Vesalius-Columbus).’[38]

Which is false, for, as shown above, and as amply detailed in

his work referred to already, Ibn al-Nafis did challenge Galen

profusely, and built his theory in complete opposition to

Galen’s.

It

is worth ending this heading with the sort of confused and

confusing, contradictory statements in relation to the role and

impact of Islamic science, which are made by most historians.

Here the culprit is

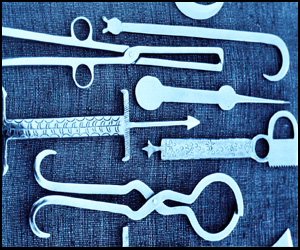

‘His

(Al-Zahrawi’s) surgical teaching, which was a distinct advance

on the surgery of the travelling mountebanks, retarded the

progress of surgery in the Latin

West, as it produced a

tendency to rely on the anatomical doctrines of Galen rather

than on actual dissections. The blame for this cannot be laid

entirely on Albucasis as the mental attitude of the scholastics

of Latin Europe was one

that leaned on the wisdom of the ancients, and thus it

was that Albucasis’ opinion of Galen’s anatomy was readily

assimilated by the West.’[39]

‘The

chief influence of Albucasis on the medical system of Europe was

that his lucidity and method of presentation awakened a

prepossession in favour of Arabic literature among the scholars

of the West: the methods of Albucasis eclipsed those of Galen

and maintained a dominant position in medical Europe for five

hundred years, i.e long after it had passed its usefulness. He,

however, helped to raise the status of surgery in Christian

Europe; in his book on fractures and luxations, he states that

‘this part of surgery has passed into the hands of vulgar and

uncultivated minds, for which reason it has fallen into

contempt.’ The surgery of Albucasis became firmly grafted on

[1]

See: D.

[2]

D. Jacquart: The Influence of Arabic medicine in the

Medieval West, in the Encyclopaedia (Rashed ed),

op cit, pp 963-84. Table pp: 981-84.

[3]

C. Burnett: The Introduction of Arabic Learning

; p. 23.

[4]

D.

[5]

C.H. Haskins: Studies, op cit, p. 131 fwd.

[6]

R.H. Major: A History of Medicine; op cit; p.

252.

[7]

Ibid.

[8]

For details on translations, see G.Sarton:

Introduction, op cit; Vol 2; pp. 167 ff.

[9]

C.J. M. Whitty: The Islamic Impact on Medicine; op cit.

[10]

For example, Anon: Here begyneth the seyuge of uryns

(

[11]

C.J. M. Whitty: the Islamic Impact on medicine; op cit;

p. 52.

[12]

N. Culpeper: A Physicall Directory, or, a Translation

of the

[13]

D. Metlitzki:

The Matter of Araby in Medieval England (Yale

University

Press, 1977),

p.13.

[14]

Daniels Von Morley Liber de naturis inferiorum et

superiorum; ed Sudhoff; p. 32; in D. Metlitzki:

The Matter; op cit; p. 60.

[15]

M.I. Shaikh: extract from ‘Penzance Manuscript; 'The

International Conference of Islamic Physicians’

Contribution to the History of Medicine

(International Institute of Islamic Medicine.) June

26-30, 1998; The International Convention Centre

[16]

H. of Carinthia: De essentiis; ed and tr C.

Burnett (

[17]

J.L. E. Dreyer: Mediaeval astronomy; in

Toward Modern

Science;

R.M. Palter ed (The Noonday Press; New York; 1961),

Vol 1, pp 235-256; p.243.

[18]

N. Daniel: The Arabs and Medieval Europe; op cit;

p. 264.

[19]

Ibid.

[20]

Ibid.

[21]

Chambers Compact: The Great Scientific Discoveries

(1991), pp

209-10.

[22]

F. Fernandez-Armesto: Millennium (A Touchstone

Book, Simon and Shuster; New York; 1995), pp. 275-6.

[23]

Ibid.

[24]

Ibid.

[25]

Ibid.

[26]

Chambers Compact: The Great Scientific Discoveries

; op cit;

pp 209-10.

[27]

F. Fernandez-Armesto: Millennium;

op cit; pp. 275-6.

[28]

A. Whipple : The Role; op cit; p. 48.

[29]

Ibid.

[30]

Ibid.

[31]

M. Meyerhof: Ibn Nafis et sa theorie sur la petite

circulation; ISIS 23. pp. 100-20.

[32]

The Sunday Times 9 June 1957. See also Journal of

History of Medicine, Vol 12 (1957), pp 248-283.

[33]

M. Meyerhof:

La Decouverte de la circulation pulmonaire par

Ibn an-Nafis; in Bulletin de l’Institut d’Egypte;

XVI pp. 33-46; Meyerhof, who en passant, does not fail

to acknowledge the pioneering achievement of Tatawi (at

p.34).

[34]

A.K. Chehade: Ibn an-Nafis et la decouverte de la

circulation pulmonaire (Paris and Damascus

; 1955).

[35]

L. G. Wilson: The problem of the discovery of the

pulmonary circulation; in Journal of History of

Medicine; vol 17;

(1962) pp 229-44.

[36]

F. Micheau: La Transmisison a l’Occident Chretien: Les

traductions medievales de l’Arabe au Latin

; in

Etats; Societes et Cultures; op cit; pp. 399-420;

pp. 417-8.

[38]

B. Mowry: From Galen's (b.130-d.200) Theory to William

Harvey's theory: A case study in the Rationality of

scientific theory; Studies in History and Philosophy

of Science; Vol 16; pp 49-82; at p. 51.

[39]

D.

[40]

Ibid; p. 88. |