Pharmacy and Pharmacology

From very early to comparatively late periods of the history of

drug-lore, Isaac explains, the preparation, action and uses of

drugs were closely associated, often indeed identified, with

witchcraft and divination.[1]

It is Islam, he pursues, which purged pharmacology of such

practices; Islamic pharmaceutical tradition, on the whole, being

rational, clean and practical.[2]

Isaac notes the saying of the Prophet: ‘li kulli da'in dawa'

(for every disease there is a remedy), is a religious

explanation: it is left to the physician, through his knowledge

and skill, to trace the right drug that God had created.[3]

Hamarneh also says that interest

in natural products and ecology was ‘a corollary to the Muslim

belief that God provides for the creatures He has created.’[4]

Hamarneh continues:

‘In Nature

God provides the right

medications for man's ailments, when and where they are most

needed. Natural medications are tokens of God's generous

attitude toward human beings, His ways of enriching their lives

and providing for their needs, a belief which prompted Muslim

naturalists, herbalists, pharmacists, and physicians to seek

remedies in nature.’[5]

Faith aside, the vast, borderless world of Islam stimulated

travel over very long

distances to procure certain plants or roots not to be found

nearer home, or to be obtained in more perfect condition than

from ordinary dealers.[6]

Ibn al-Baytar (1197-1248), thanks to his travels, managed

to accumulate a vast knowledge in the field.

His extensive travels began in 1216-7 in search and

collection of plants. In Bejaia

, in

Muslim pharmacists

discovered new and simple

drugs in their crude forms, and gave detailed descriptions of

their geographical source, physical properties, methods of

application, the pharmaceutical forms of the remedies used, and

the techniques employed in their manufacture.[12]

Some writers emphasised the botanical description of the

drugs; others their potency, their mode of operation, their

composition, and the forms which the medicaments took (that is

to say, preparations like pastes, solutions, tinctures, etc.),

and also synonyms for drugs, and other topics.[13]

Ibn Sahl (d. 869) was the first physician to initiate

pharmacopoeia, describing a large variety of drugs and remedies

for ailments.[14]

Ibn Sina

,

described no less than 700 preparations, their properties, mode

of action and their indications in his Canon.[15]

Such information can

also be found in works (generally bearing the title

Jami al-adwiya al-mufrada (Collection of Simples)

such as those of Ibn Samjun (d. 1002), al-Ghafiqui

(d.1165), Ibn Rumia (1142-1218) and others’ treatises on

simples; Ibn Rumia, for instance, introduces new methods of

investigating properties and uses of drugs.[16]

Al-Biruni

(d 1051), in his

Kitab al-Saydalah (Pharmacology), lists and describes the

properties of drugs, giving the technical terminology for

categories of drugs; the general theory of medicaments,

therapeutic properties of substances, etc.[17]

In the introduction to his Book of Drugs, Al-Biruni explains:

‘Everything that is absorbed, voluntarily or unconsciously, can

be divided first of all into foods and poisons. Remedies are

placed half way between these two. Foods receive their qualities

from active and passive forces, and primarily from their four

degrees, so that the body, in equilibrium, has the power to

transform nutriment into its own substance by complete digestion

and by assimilation, thus replacing what part of the diet has

been lost by disassimilation. That is the reason why the body

must act on food before it can derive any benefit from it. As

for poisons, they receive their qualities from the same forces

but at their highest degree, which is the fourth, in such a way

that they overpower the body and subject it to morbid and fatal

transformations…. As for drugs, they are placed between the two,

because they are corruptive with respect to food and curative

with respect to poisons. Their curative action can be wrought

only by skilful and scrupulous physicians. In addition, there

are the medicinal foods, half way between drugs and food, and

the toxic medicaments, half way between drugs and poisons.’[18]

Minerals had great significance as remedies among the Muslims.

Antimony is said to have been recommended for ophtalmia by the

Prophet himself, and turns up regularly in Arabic literature on

eye disease.[19]

In dermatology, we find early mention of ointments containing

sulphur and mercury.[20]

By the time of Al-Zahrawi the external use of these substances

was obviously a major concern of the Muslim physicians.[21]

In the oldest Muslim lapidary extant, by Utarid Ibn Mohammed

al-Hasib (9th century) Kitab manafi’ al-ahjar or

Kitab al-jawahir wa’l Ahjar (The Book of Virtues of Minerals

or the Book of Precious Stones and Minerals), the properties of

precious stones are described.[22]

Ibn Sina

in his Kitab al-Shifa

(the Book of Healing), devotes a section to mineralogy, which

includes stones and various chemicals.[23]

On vitriols, he says:

‘The

vitriols are composed of a salty principle, a sulfurous

principle and stone, and contain the virtue of some of the

fusible bodies (metals). Those of them which resemble qalqand

and qalqatar are formed from crude vitriols by partial

solution, the salty constituent alone dissolving, together with

whatever sulferity there may be. Coagulation follows, after a

virtue has been acquired from a metallic ore. Those that acquire

the virtue of iron become red of yellow, e.g. qalqatar,

while those which acquire the virtue of copper become green. It

is for these reasons that they are so easily prepared by means

of this art.’[24]

As

excellent organisers of knowledge, Levey points out, Muslim

writers directed their pharmacological texts along paths which

either seemed more promising or more useful to the apothecary

and medical practitioner.[25]

Ibn Massawayh (Junior) (d.1015), for instance, was to became

famous in the Latin

West for his

pharmacopoeia, which was divided into several sections, dealing

with correctives to medicines, simple purgative remedies,

composite medicines and lastly medicines as intended for each of

the specific individual diseases.[26]

The Muslims also appended to each name its synonyms in other

languages in order to arrive at as unambiguous a definition of

the drugs as possible.[27]

Ibn al-Baytar’s greater merit, for instance, was in the

systematisation of the discoveries made by Muslims in the Middle

Ages, and he was also concerned with finding the technical

equivalents between Arab, Berber, Greek, Latin, Persian and

Romance languages.[28]

Considering such materials, Dietrich concludes, shows

that the Muslim pharmacists did not, after all, compile their

material in as cavalier a manner as has sometimes been said of

them.[29]

Also, contrary to what is generally assumed, the Muslims largely

surpassed their predecessors in the field. First of all in their

numbers, Meyerhof

was able to trace about a hundred and ten writers who worked in

this field.[30]

The Muslims also added several hundred drugs to the stock of

medicaments known to the Greeks.[31]

Ibn Juljul (d.944), for instance, introduced a whole range of

new medical plants into therapeutics.[32]

Ibn Juljul was conscious of the fact that since the days of

Dioscorides medicine and botany had developed new items used for

medication which had come from the East, or were found in

Andalus. He produced a Supplement "on those drugs which

Dioscorides did not mention", containing around sixty items.[33]

Leclerc has calculated that the thirteenth century botanist Ibn

al-Baytar listed some 200 plants which were unknown to

Dioscorides;[34]

others cite an even larger figure approaching a thousand.[35]

All in all, and in quantity, the number of simples and compound

remedies rose under the Muslims to about 4,000 in the later

works, which is a considerable number compared to the mere

hundreds in the Greek works.[36]

More importantly, as with every science, the Muslims were not

merely followers of the Greek as scholarship tends to accuse

them of being. Ibn

Wafid (Abenguefith to his Latin

translators), the vizier

and director of the botanical garden of the princely house of

Toledo

,

and the author of the earliest pharmacopoeia treatise in the

Muslim West, for instance, bases himself on the ancients, but

takes into account the remedies he has himself seen used to good

effect in Spain.[37]

The same with Ibn Juljul, who used and respected the ‘Ancients’

but did not simply transmit the Greek learning; he made valuable

contributions to the practical knowledge and use of medicinal

plants, and was held in high respect by contemporary and later

scholars and physicians.[38]

As

pharmacology made progress, Levey points out, other sciences

advanced to keep up with it.[39]

In the early Muslim period, as he explains, pharmacology was the

mother of chemistry. In this way, the Muslims provided ample

information

regarding chemicals and their physical and chemical properties

and reactions.[40]

This process of elaboration was carried on by the scholars of

the Christian West until the breakthrough in chemistry a few

hundred years ago.[41]

Developments in Muslim chemistry including filtration,

distillation and crystallisation also had a decisive impact on

the rise and growth of modern pharmacy.[42]

Cosmetology is one area, little known, which benefited greatly

from progress in pharmacology. Al-Zahrawi, in the 19th

volume of his Al-Tasrif, considers cosmetics a definite

branch of medication (Adwiyat al-Zeenah). He looks at the

care and beautification of hair (mentioning hair dyes), skin,

teeth and other parts of the body. He has his solutions for

mouth hygiene, and bad breath for which he suggests cinnamon,

nutmeg, cardamom and chewing on coriander leaves. He also

includes methods for strengthening gums and bleaching the teeth.

He deals with body odours and fighting them with perfumes,

scented aromatics and incense, and included under-arm

deodorants, hair removing sticks and hand lotions. Al-Zahrawi

mentions the benefits of suntan lotions, describing their

ingredients in detail, and describes nasal sprays and hand

creams. Al-Zahrawi also suggests keeping clothes in an incense

filled room to make them carry a pleasant fragrance for the

wearer.[43]

Sahlan ibn Kaysan’s (d.990) Mukhtassar fi al-Adwiya

al-murakabba al-musta’mala fi akhbar al-amrad (Compounded

Drugs Used in Most Ailments) has chapters which deal with

myrobalan confections, electuaries, pills, aperients, pastilles,

powders, syrups, lohochs, and robs, gargles, collyria,

suppositories, pessaries, poultices, oils and lotions, buccal

medicines and dentifrices, and pomades.[44]

Many variations of this type of text were known.[45]

Likewise, those whose work led to perfumery and distillatory

operations learned to provide more suitable raw material for the

apothecary and physician.[46]

With pharmacology and its related sciences there naturally

developed experimentation. Muslim practioners experimented with

drugs in order to learn more about their effect on humans, often

using a single drug in the treatment of each ailment in order to

determine its precise effect.[47]

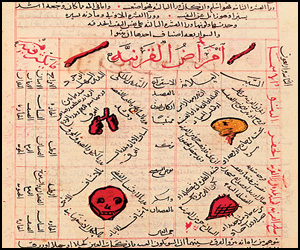

Experiments were reported in notebook collections of case

histories, sometimes known as al-Mujarrabat; whilst other

manuals included charts, diagrams, and tables that dealt with

drugs and diseases listing their causes and symptoms, their

seasonal prevalence, and the dosages of drugs administered.[48]

Others included mathematical calculations concerning the potency

of drugs and the recommended dosages according to age, sex, and

the severity of the sickness.[49]

Several physicians prescribed and compounded their own

medications, giving them specific names, from the recipes they

formulated themselves, often indicating the pharmacological

action that would result, a practice usually followed with

modern patented medicines.[50]

Al-Zahrawi’s (940-1013)

al-Tasrif, known in Latin

as liber servitoris

de praeparatione medicinarum simplicium, for instance,

describes chemical preparations, tablet making, filtering

extracts, and related pharmaceutical techniques.[51]

The

Islamic impact on the Christian West in the subject was quite

enormous, and this is highlighted by the briefest of outlines.

In terms of collections of recipes for medicines, the huge

corpus of Islamic pharmacology and plant learning influenced

these very heavily- indeed some of these works were almost

direct cribs from the original works of writers like Ibn

Massawayh.[52]

The Antidotarium of Ibn

Massawayh (d. 857) (Mesue) was plagiarised and copied

into books of medical recipes for six hundred years.[53]

Some of these Western works relying on Islamic

pharmacology are almost exclusively medical, for example, Andrew

Borde's The Breviarie of Health.[54]

Some are a mixture of medicines and handy hints on domestic

matters like how to scent gloves, or make marmalade, such as

Partridges bestseller The Huswives Closet and its sister

volume The Widowes Tresure.[55]

In a separate category were the herbals, books which combine

some botany with medicine.[56]

Herbals were possibly the most popular and long lived of them

all-the most famous of them, Culpeper's Herbal, is still

in print and can be obtained in any British bookseller to this

day, containing recipes which the Islamic writers of one

thousand years ago would recognise as their own.[57]

The impression that Islamic drugs dominated medical practice is

supported by examining customs records or apothecaries books.[58]

In the late 17th century, an edition was made of the

London Dispensatory. Its list of botanicals, simples, minerals,

compound drugs for external and internal uses, oils, pills,

cataplasms, etc, also highlights this Muslim influence.[59]

Subsequently, parts of the Latin

version of Ibn

al-Baytar’s Simplicia

were printed in 1758; whilst Ibn Sarabi and Ibn Massawaih

were studied and summarized for the use of European

pharmacopoeias until about 1830.[60]

Latin and German translations, and limited Spanish

version of Ibn Al-Baytar’s pharmaceutical compendium,

Kitab-ul-Jami fil Adwiyah al-Mufradah (Dictionary of Simple

Remedies and Food), were made before a complete translation

appeared in 1842.[61]

There is today a fairly adequate number of secondary sources

dealing with the history of Muslim pharmacy. Meyerhof has

written many works of great interest, which constitute major

sources of reference.[62]

Ulmann is another good source albeit he remains available in

German mainly;[63]

which is also the case for Meyer.[64]

Levey’s work in English on early Muslim pharmacy is excellent.[65]

Original Islamic manuscripts constitute the best source to know

more on the subject. However, these manuscripts remain to a

great extent untouched. Dietrich observes that approximately

a quarter of the extensive Muslim production is probably extant,

and very little of it printed, most of it in manuscript form in

libraries, especially those of the East.[66]

It is all the more crucial to access such sources, because, as

Levey insists, the impact of Muslim pharmacology lasted

into the 19th century in the West, and as a result of

its accumulation of data from over thousands of years’

experience, this may continue to lead to valuable facts today.[67]

Medicinal properties of botanical sources known by Muslim

physicians and apothecaries deserve greater attention than has

been possible hitherto.[68]

Some important medicinal plants have been explored as to their

physiologically active principles and chemical activity with

success, but more of this remains to be done, for some clues

leading to potentially valuable drugs may still be found in the

medical Islamic texts.[69]

Levey lists some of the works that deserve translation into

English:

-Al-Ansari (d. 1292): Al-Simat fi asma' al-Nabat (Special

Considerations on Names of Plants); (MS: Bibliotheque Nationale,

Paris, Arabe 3004).

-Ishaq B. Sulaiman: (903? 953?): Kitab al-Aghdhiya wa'l

adwiya (Book on Nutritives and Drugs); (MS. Munchen 809).

-Al-Tamimi (late 10th): Kitab al-Murshid ila jawahir

al-Aghdhiya waquiwa'l-mufradat min al-Adwiya (Guide Book on

Nutritives and the Properties of Simple Drugs); (MS Bibliotheque

National Arabe 2870).

-Ibn

Jazla (d. 1100): Minhaj al-bayan fima vasta' Miluhu'l-insan

(Manual of Explanation in What One Employs); (MS Leiden 1355; MS

Shebit Ali 2107).

-Al-Kuhin b.Attar: Minhaj al-Dukkan (Manual of the

Pharmacy

);

(MS Leiden 1360; MS Munchen 833.)[70]

[1]

H.D. Isaac: Arabic Medical Literature: in Religion;

M.J.L. Young et al ed; op cit; pp 342-64; p. 361.

[2]

Ibid.

[3]

Ibid.

[4]

S.K.

Hamarneh: The Life Sciences: in The Genius; J.R.

Hayes ed; op cit; p. 156.

[5]

Ibid.

[6]

H.D. Isaac: Arabic Medical Literature; op cit; p. 362.

[7]

L. Leclerc: Histoire; op cit; vol 2; p. 226.

[8]

Ibid.

[9]

J. Vernet and J. Samso: Development of Arabic Science in

[10]

Ibid.

[11]

[12]

S.K. Hamarneh: The Life Sciences; op cit; p. 156.

[13]

A Dietrich: Islamic

Sciences and the Medieval West, Pharmacology in

Islam and the Medieval West; I.K. Semaan;

ed (State University of New York, Albany; 1980), pp

50-63: p.50.

[14]

E.S. Kennedy: Al-Biruni

; in Dictionary of Scientific Biography; op cit;

vol 2; pp. 147-58; at p. 155.

[15]

Volume ii includes the names of simple drugs arranged in

alphabetical order.

[16]

Max Meyerhof. (1935 b) Esquisse d'Histoire de la

pharmacologie et de la botanique chez les Muslmans

d'Espagne', Al-Andalus

3; pp. 1-41.

[17]

E.S. Kennedy: Al-Biruni

; op cit; vol 2; pp. 147-58; at p. 155.

[18]

In R. Arnaldez-L.Massignon: Arabic Science; op cit; p.

419.

[19]

Browne, 1921; in R.P. Multhauf: The Origins of

Chemistry; op cit; p.217.

[20]

Friedman (1938) mentions both in connection with

al-Tabbari in R.P. Multhauf: The Origins of Chemistry;

op cit; p.217..

[21]

R.P. Multhauf:

The Origins of

Chemistry; op cit; p.217.

[22]

M. Levey: Early Arabic Pharmacology; op cit; p.

164.

[23]

R.J. Holmyard and D.C. Mandeville: Avicennae de

Congelatione et Conglutinatione lapidum; being

sections of the Kitab al-Shifa; pp. 39 ff.

[24]

M. Levey: Early Arabic Pharmacology; op cit; p.

165.

[25]

M. Levey: Influence of Arabic Pharmacology on Medieval

Europe; in Convegno Internationale:, op cit; pp.

431-44. p. 438.

[26]

G. Wiet et al: History; op cit; p. 663.

[27]

A Dietrich: Islamic

science; op cit; p.52.

[28]

E. Calvo: Ibn al-Baytar, in Encyclopaedia of the

History of Science (Selin ed), op cit; p.

404.

[29]

A Dietrich: Islamic

science; op cit; p.50.

[30]

M. Meyerhof in A

Dietrich: Islamic science; op cit; p.52.

[31]

Ibid.

[32]

L. Leclerc: Histoire de la Medecine;

in A.

Dietrich: Islamic sciences; op cit; p.55.

[33]

P. Johnstone: Ibn Juljul; in Islamic Culture

(1999), pp. 37-43; at. p.39.

[34]

Ibn al-Baytar

Kitab-ul-Jami fil Adwiyah al-Mufradah; in L.

Leclerc: Histoire de la Medicine Arabe; op cit;

vol 1; p. xi.

[35]

See J. Vernet and J. Samso: Development, op cit, pp

271-2, and N. Leclerc: Histoire; op cit; pp. 226

ff.

[36]

M. Levey: Early Arabic; op cit; p. 173.

[37]

G. Wiet et al: History; op cit; p

.659.

[38]

P Johnstone: Ibn Juljul; op cit; p. 42.

[39]

M. Levey: Early Arabic, op cit, p. 53.

[40]

Ibid, p. 173.

[41]

Ibid.

[42]

C.J.M. Whitty: The Impact of Islamic Medicine; op cit;

p. 49.

[43]

Mainly derived from the following sources:

-S.K Hamarneh and G. Sonnedecker: A Pharmaceutical

View of Albucassis Al-Zahrawi in Moorish

-M. Levey: Early Arabic, op cit.

[44]

M. Levey: Influence of Arabic Pharmacology on Medieval

Europe; op cit; p. 438.

[45]

P. Sbath and C.D. Avierinos: Deux Traites Medicaux

(Cairo

; 1953).

[46]

M. Levey: Early Arabic, op cit, p. 173.

[47]

S.K. Hamarneh:

The Life Sciences; op cit; p. 156.

[48]

Ibid.

[49]

Ibid; p. 156-7.

[50]

Ibid; p. 157.

[51]

See G. Sarton: Introduction; vol 1; op cit. p.

534.

[52]

J.C.M. Whitty: The Impact of Islamic Medicine; op cit;

p. 52.

[53]

Ibid; p. 49.

[54]

A. Borde: The

breviarie of health; wherin doth follow remedies, for

all manner of sickneses and diseases, the which may be

in man or woman (

[55]

J. Partridge: The tresurie of comodious conciets, and

hidden secrets, and may be called, the huswives closet,

of healthful provision; (

[56]

Herbals overlapped very considerably, and were usually

variations on a theme. An example is Anon: Here

begynneth a newe mater: the which is called an herbal

(

[57]

N. Culpeper: Culpeper's Complete Herbal;

Wordsworth, (

[58]

For example, R.S. Roberts: The Early History of the

Import of drugs into

[59]

M. Levey: Early Arabic, op cit, op cit; p. 177.

[60]

E. J. Jurji: The Course of Arabic.

p. 249.

[61]

For details, see N.L. Leclerc: Histoire de la

Medecine; vol 2; pp. 233-4.

[62]

M. Meyerhof: ‘Uber die Pharmacologie und Botanik des

Ahmad al-Ghafiqi', Archiv fur Geschichte der

Mathematik und Naturwissenschaft 13 (1930), pp.

65-74.

-M.Meyerhof: Esquisse d'histoire de la pharmacologie et

de la botanique chez les Musulmans d'Espagne',

al-Andalus 3, 1935: pp. 1-41.

[63]

M. Ullmann: Medizin in Islam (Leiden/Cologne,

1970).

"

" : Die Natur und Geheimwissenschaften im

Islam,

[64]

E. H. F. Meyer: Geschichte der Botanik, I-IV

(Konigsberg,1854-7).

[65]

M. Levey: Early

Arabic Pharmacology (E. J. Brill; Leiden, 1973).

[66]

A Dietrich: Islamic

science; op cit; p.52.

[67]

M. Levey: Influence of Arabic Pharmacology on Medieval

Europe; op cit; p. 431.

[68]

Ibid.

[69]

Ibid.

[70]

M. Levey: Early Arabic, op cit, pp 58-9. |