Hospitals

[1]

Whilst travelling in the Near East in the years

1183-5, Ibn Jubayr

noted one or more hospitals in

every city in the majority of the places he passed through,

which prompted him to say that hospitals were one of ‘the finest

proofs of the glory of Islam,' (and the madrasas another).[2]

Some twenty or so years before, in 1160, another

traveller, Benjamin of Tudela, found no fewer than sixty well

organized medical institutions in

Possibly the earliest hospital in Islam was a mobile

dispensary following the Islamic armies, dating from the time of

the Prophet, a tradition which remained throughout the centuries

of Islamic glory.[5]

The first known hospital in Islam was built in

More hospitals were erected, and by the 12th

century, the institution of the hospital in Islam had reached

very advanced standards as seen in these instances. In

In

In

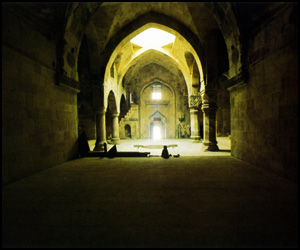

‘Within

a spacious quadrangular enclosure four buildings rose around a

courtyard adorned with arcades and cooled with fountains and

brooks. There were separate wards for diverse diseases and for

convalescents; laboratories, a dispensary, out-patient clinics,

diet kitchens, baths, a library, a chapel, a lecture hall, and

particularly pleasant accommodations for the insane. Treatment

was given gratis to men and women, rich and poor, slave and

free; and a sum of money was disbursed to each convalescent on

his departure, so that he need not at once return to work. The

sleepless were provided with soft music, professional

story-tellers, and perhaps books of history.’[22]

Major adds that the income devoted to this hospital

by the Mamluk rulers was the equivalent of $100,000 a year, and

that each patient received the equivalent of $12 (1954 value) on

their dismissal from the hospital.[23]

Pushmann acknowledges how the Muslims developed the

hospital institution on efficient lines.[24]

Muslim hospitals, indeed, were managed according to standards

that compare favourably with those of today. Nearly all

hospitals

had

separate wards for male and female patients, with different

wards for the different therapeutic branches, such as medicine,

surgery, orthopedics and eye diseases.[25] A separate ward or

pavilion, with barred windows, was used for the care of the

mentally ill, whilst a pharmacy, in the charge of a competent

and licensed pharmacist, was used for both the Out-Patient and

In-Patient services.[26]

Care for the patients was

not just during stay at hospital, but also after. At Al-Mansuri

of

Hospitals

were the perfect symbol of

universality of health care in Islam, and unlike their

successors elsewhere, they catered for the needs of all, rich

and poor alike, in urban and in rural areas, and freely. This

attitude derives directly from the Qura’nic text which imposes

upon the believer to give care and cure to every human

regardless of their rank in society, including slaves.[32]

For instance, Ibn Abi Usaybi'a speaks of an eminent Syrian

doctor of the 12th century, who, after examining the

sick in the hospital, went to court to treat the important

people.[33]

The constitution establishing the Al-Mansuri hospital in

Hospitals

were places of care and also of

learning and training. Hence, the leading figures of Islamic

medical science who worked as directors of hospitals also took

the lead in generalising the practice of studying patients and

preparing them for student presentation.[36]

At al-Nuri

‘And

one of those things which are more incumbent on the student of

this art, are that he should constantly attend the hospitals and

sick houses; pay unremitting attention to the conditions and

circumstances of their inmates, in company with the acute

professors of medicine; and enquire frequently as to the state

of the patients and symptoms apparent in them, bearing in mind

what he has read about these variations, and what they indicate

of good and evil.’[45]

As places of learning, the hospitals were also richly

endowed with libraries. Nur Eddin Zangi (r. 1146-1174)

constituted into waqf a large number of books on medicine for

the

Having looked briefly at the Islamic hospital, which

in its main features and operations, reflects the modern day

hospital, we can safely assert, that this institution was born

under Islam, and not under some previous civilisations,[53] which at no instance

shows one single advanced form of management or operation, or

state involvement, as was the case with the Islamic hospital.

Watts insists that we should remind ourselves that in earlier

times, in the world of

The best Islamic hospitals, Whitty says, were several

centuries in advance of European ones, although to what extent

they directly influenced European practice is difficult to

quantify.[55] Meyerhof, however,

makes an outline of the Islamic impact upon the Christian West

in this field, stressing the role of the crusades.[56] Western

hospitals, he notes, may well

have been imitations of such splendidly installed ‘Bimaristans’

as that of the contemporary Seljuk ruler Nur Eddin in

The hospital institution in its rise reflects the

glory of Islamic civilisation. In its collapse it also reflects

the collapse of the same civilisation. In 1258 the Mongol Hulagu conquered

[1] See A Issa Bey: Histoire des hopitaux en Islam; op cit.

[2]

Ibn Jubayr

: Travels, op cit,

Vol 3, p. 330.

[3]

Rabbi Benjamin of Tudela, Itinerary,

Vol. I (

[4]

R.H. Major: A History of Medicine; op cit; p.

260.

[5] A. Djebbar: Une Histoire; op cit; p. 319.

[6]

G. Wiet et al: History; op cit; p. 651.

[7]

E. Abu Leish: ‘Contribution of Islam to medicine' in

Islamic Perspective, op cit; pp. 15-44.

p 22.

[8]

F.S. Haddad in I.B. Syyed: Medicine and medical

education in Islamic history, in Islamic Perspectives;

op cit; pp 45-56, p. 48.

[9]

S.K. Hamarneh: Health Sciences in Early Islam, 2

vols, edited by M.A. Anees, vol I

(Noor Health Foundation and Zahra Publications,

1983), p. 101.

[10]

Al-Maqrizi: Khitat, vol 2, p 405.

[11]

S. Hamarneh: Health Sciences; op cit; p. 102.

[12]

S.K. Hamarneh: Health Sciences; op cit. p. 100.

[13]

Ibn Jubayr

: Rihlat, op cit,

pp 283-4.

[14]

S.K. Hamarneh: Health Sciences, op cit; p. 100.

[15]

Abd al-Wahid al-Marrakushi: Al-Mu’jib fi Talkhis

Akhbar al-Maghrib

, R. Dozy, ed (

[16]

Ibid.

[17]

Ibid.

[18]

Ibid.

[19]

E.T. Withington: Medical History From the Earliest

Times (1894); p. 166.

[20]

E.T. Withington: Medical; p. 166; D. Guthrie:

A History of Medicine; op cit; p. 96.

[21]

F.S. Haddad in I.B. Syyed: Medicine and medical

education; op cit; p. 48.

[22]

W. Durant: The Age of Faith; op cit; pp 330-1.

[23]

R.H. Major: A History of Medicine; op cit; p. 260

[24]

T. Puschmann: History of Medical Education

; English tr by E.H. Hare (

[25]

A. Whipple: The Role; op cit; p.81.

[26]

Ibid.

[27]

Al-Makrizi: Khitat, vol 2, op cit; p 405.

[28]

A. Whipple: The Role; op cit; p. 81.

[29]

I. B. Syed, Medicine, op cit, p. 45

[30]

S. Hamarneh: Health Science; op cit; pp 100 ff.

[31]

R.H. Major: A History of Medicine; op cit; p.

232.

[32]

Cited in A.Djebbar: Une Histoire; op cit; pp

318-9.

[33]

Ibn Abi Usaybi'a ‘Uyun, p. 628 in F. Micheau, The

Scientific Institutions, op cit, p. 1001.

[34] A. Isa Bey: Histoire des hopitaux; op cit; p. 151.

[35]

G.Sarton: Introduction, Vols I and ii in

particular.

[36]

I. B. Syed: Medicine, op cit, p. 45

[37]

Ibn Abbi Ussaybi'ah: ‘Uyun al-anba' fi

Tabaquat al-Attiba, edited by A. Mueller (Cairo

/Konigsberg; 1884,

reprint, 1965), vol 3, pp 256-7.

[38]

Ubn Abi Usaybia: Uyun al-Anba… (

[39]

A. Whipple: The Role; op cit; p.81.

[40]

Al-Makrizi, Al-Khitat, op cit, II, p. 406.

[41]

S.K. Hamarneh: Health Sciences; op cit; p. 99.

[42] A. Djebbar: Une Histoire; op cit; 319.

[43]

R.H. Major: A History of Medicine; op cit; p.

232.

[44]

G. Wiet et al: History; op cit; p. 653.

[45]

R.H. Major: A History of Medicine; op cit; p.

241.

[46] Y. Eche: Les Bibliotheques; op cit; p. 235.

[47]

Ibid.

[48]

Al-Safadi: Al-Wafi bi’l wafayat; Ms of Ahmad III;

[49]

Al-Makrizi: Al-Khitat; op cit; II; p. 407.

[50]

Al-Nuwayri: Nihaya; op cit; 30; r.

[51]

Al-Safadi: Al-Wafi bi’l wafayat;

op cit; XX; p. 162; r..

[52]

Ibid; p. 162; r..

[53]

As found in G. E. Gask and John Todd:

"The Origin of Hospitals

," in Science, Medicine (E A. Underwood, ed); op

cit; vol I; 1953.

[54]

S. Watts: Disease and Medicine; op cit; p. 49.

[55]

C.J.M. Whitty: The Impact of Islamic Medicine; op cit;

p. 48.

[56] M. Meyerhof: Science and medicine, op cit;

at pp 349-50.

[57]

Ibid.

[58]

Ibid.

[59]

Ibid.

[60]

C.J.M. Whitty: The Impact of Islamic Medicine; op cit;

p. 48.

[61]

Ibid.

[62]A.

Whipple: The Role ; op cit ; p. 86.

[63]

Ibid. |