Water Lifting Devices

Transferring water to a particular level or over long distances,

for a diversity of purposes, such as irrigation, supplying water

to private and public places, or pumping water out of flooded

mines, has relied on a variety of water raising machines. These

machines have constituted matters of focus for Islamic

engineers. In relation to the latter cited problem, Al-Qazwini,

the 13th century geographer, speaks of a mine where

water was found at a depth of 20 cubits.[1]

To clear the water from the mine shaft a wheel was set on it and

it served to force it up to a tank placed at a higher level.

Here, the process was repeated and the water was pumped to a

second tank, from which by means of another wheel it was raised

to the surface.[2]

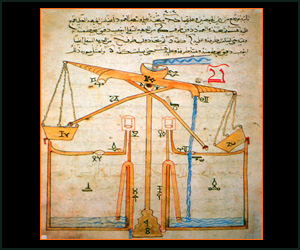

A number of water lifting devices were either improved or

developed by Muslim engineers, craftsmen, and users. These

include the shaduf or swape, the saqiya or chain

of pots, and the noria (a wheel driven by water) and pumps.

There is no room here to dwell on the description of these

devices beyond a couple of lines on their most central features.

The saqiya, for instance, is a chain of pots driven through a

pair of gear wheels by one or two animals harnessed to a draw

bar and walking around a circular track.[3]

The chain of pots could also be driven by a treadmill, mounted

on the same axle as the wheel carrying the chain of pots. The

crux of this machine is the gear, which has the function of

altering the motion from horizontal to vertical.[4]

There are plenty of references to the machine in the 10th

century works of Islamic geographers,[5]

and there is a full description of the machine in the 17

volume encyclopaedia written by Ibn Sida who died in 1066.[6]

In the farming manual by Ibn al-Awwam, there is another

description, which includes the interesting comment that the

pot-garland wheel should be made heavier than is usual in order

to make the machine operate more smoothly. This is a clear

indication that Ibn al-Awwam understood the principle of the

fly-wheel.[7]

The use of the saqiya was introduced to the

The noria is perhaps the most significant of the traditional

water raising machines, being driven by water, it is self acting

and requires the presence of neither man nor animal for its

operation. There are excellent, detailed descriptions of this

device, available in many works, such as Schioler’s, for

instance.[9]

Briefly, here, the noria is a large wheel driven by water. It is

mounted on a horizontal axle over a flowing stream so that the

water strikes the paddles that are set around its perimeter, and

the water is raised in pots attached to its rim or in bucket

like compartments set into the rim.[10]

The norias were widespread in the

Norias were widely used in Muslim Spain, too, at

Some Muslim engineers who designed or built such machines are

known to us. Al-Jazari was amongst them. His designs contradict

the generally established view amongst Western historians who

assert that his devices, like those of other Islamic engineers,

were mere fanciful creations with no practical purpose. His

treatise contradicts such widespread distortions.[19]

Not only, it is almost certain that he was involved in the

design and construction of public works, but his designs have

also incorporated techniques and components that are of

importance for the development of machine technology.[20]

One of his machines, a miniature water driven saqiya (category

V; ch 3), was provided with a model cow to give the impression

that this was the source of motive power, whilst the actual

power is provided in a lower, concealed chamber and consists of

a scoop wheel and two gear wheels.[21]

This system drives the vertical axle that passes up into the

main chamber, where two further gear wheels transmit the power

to the chain of pots wheel.[22]

Such devices, without the model cow, were in every day use,

al-Jazari’s model being a smaller version of a larger one, used

on the River Yazid in

Islamic history has also retained the name of a water wheel

constructer: Qaysar (fl 12th-13th

centuries) who is credited for building some gigantic wheels

adorning the Syrian landscape,[24]

especially on the Orontos river.

Water

raising devices are not

just important, as outlined so far, for their economic and

social roles, but are also important for another crucial reason.

Indeed, as Hill points out, they are of considerable

significance in the history of machine technology, since many of

the ideas and components incorporated in such water lifting

devices were to enter the vocabulary of European engineering at

a later date.[25]

In one of

Al-Jazari’s devices, for instance, we have the crank as part of

a machine, although manually operated cranks have been in use

for centuries.[26]

In another of his machines, listed as al-Jazari’s First Water

Raising Machine, the segmental gear plays an interesting part.[27]

A similar wheel first appeared in Europe in Giovani De’Dondi’s

astronomical clock, completed about 1365;[28]

but this type of gear was already known in the Islamic world

before the time of Al-Jazari, through al-Muradi (fl. 11th

century) of

Another type of wheel was also widely used in Islam, but to

provide power; water and wind playing a central role in

activating machinery in Islam.

[1]

Qazwini: Athar al-Bilad, in M.C. Lyons: Popular

Science; op cit; p. 52.

[2]

Ibid.

[3]

D.R. Hill: A History of Engineering; op cit; p.

135.

[4]

Ibid.

[5]

Such as Al-Muqaddasi: Ahsan al-Taqassim; op cit;

p. 208; Ibn Hawqal: Kitab Surat al-Ard; vol 2; p.

324.

[6]

E. Wiedemann and F. Hauser: Uber Vorrischtungen zum

Heben von Wasser in der islamischen Welt; Jahrbuch

des Vereins Deutscher Ingenieure; vol 8 (1918), pp.

121-54; p. 129.

[7]

Ibn Al-Awwam Libro; op cit; in T. Schioler: Roman and

Islamic Water

Lifting Wheels

(Odense

University Press; 1973), p. 30ff.

[8]

N. Smith: Man and Water

;

op cit; p. 20.

[9]

T. Schioler; op cit; pp. 37-8.

[10]

D.R. Hill: Hydraulic machines; in Encyclopaedia of

Islam; op cit; vol 5; under ma’a; p. 861.

[11]

G. Sarton:

Introduction;

op cit; vol 2; p. 623.

[12]

H. Suter: Die

Mathematiker und Astronomen der Araber und ihre Werke

(APA, Oriental

Press,

Amsterdam, 1982). p. 33.

[13]

Nasir Khusraw; p. 5. in G. Le Strange: Palestine

Under the

Moslems

(Alexander P. Watt; London; 1890), p.357.

[14]

Al-Dimashqi:

Kitab

nukhbat al-dahr fi ajaib al-barr wal bahr,

edited by A.F. Mehren; quarto, 375 p.

(St Petersburg; 1866).

[15]

D. Sourdel:

[16]

M. Sobernheim:

[17]

N. Smith: A History of Dams

;

op cit; pp 90-1.

[18]

Al-Idrisi: Description de l’Afrique du Nord et de

l’Espagne; Arabic text ed.

With French Tr by R. Dozy and M.J. de Goeje (Brill;

Leiden; 1866), p. 187 in Arabic, and 228 in French.

[19]

D.R. Hill: The Book of Knowledge, op cit.

[20]

D.R. Hill: A History of Engineering; op cit; p.

146.

[21]

D.R. Hill: Hydraulic machines; in Encyclopaedia of

Islam; op cit; vol 5; p. 861.

[22]

Ibid.

[23]

D.R. Hill: A History of Engineering; op cit; p.

148.

[24]

R.J. Forbes: Studies in Ancient Technology

; vol II, second revised edition (Leiden, E.J Brill,

1965), p. 114.

[25]

D.R. Hill: A History of Engineering; op cit; p.

129.

[26]

Ibid; p. 149.

[27]

Ibid; pp. 147-8.

[28]

S. A.Bedini and F.R. Maddison: Mechanical Universe, the

Astrarium of Giovanni de Dondi, Transactions of the

American Philosophical Society; New Series; vol 56

(1966).

[29]

D.R. Hill: A History of Engineering; op cit; p.

148.

[30]

Ibid; p. 149-52.

[31]

Ibid; p. 152. |