Urban Imperatives

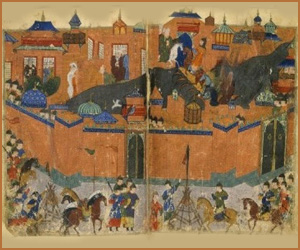

Fast urban growth in the

Islamic world today is symbol of, or synonymous with, chaos,

which is in sharp contrast with medieval Islam. Then, urban

growth proceeded alongside order, aesthetics, and inclusive of

basic amenities. Udovitch has noted how Islamic cities provided

economic opportunities, and with their mosques, madrasas,

churches, synagogues, schools, bathhouses, etc, contained all

that was needed for leading ‘a religious and cultured life.’[1]

Oldenbourg equally captures both comfort and fullness of Muslim

urban life including necessary amenities as well as social and

economic services.[2]

A picture common to the better known cities such as

The economic sustenance of the Islamic city was no

less crucial. Durant points out that cities and towns swelled

and hummed with transport, barter, and sale; pedlars cried their

wares to latticed windows; shops dangled their stock and

resounded with haggling; fairs, markets, and bazaars gathered

merchandise, merchants, buyers, and poets; caravans bound to

China

and India

, to Persia

, Syria

, and Egypt

; and ports like Baghdad

, Basra

, Aden, Cairo

, and Alexandria sent Arab merchantmen out to sea.[12] The workshops of

One of the dominant urban necessities is water

supply. And should one ponder briefly on the chaos prevailing in

the water supply of Middle Eastern and

In the Muslim West,

in Marrakech

, water was brought to the city for drinking and irrigation by mainly

subterranean canals from the mountains twenty miles to the

south.[44]

In

Baths

dominated the Islamic urban and

social landscape, and were found alongside numerous pools;

frequent washing part of religious duty for Muslims.[55] Hot baths were thus in

use in the Muslim world from the 7th century onwards.[56] The great cities of

the East possessed conduits of running water; and everywhere

could be found many pools and baths.[57]

The baths of Damascus

, meticulously constructed, were numerous; the historian, Ibn al-Asakir

pointing out that during his era, the second half of the 12th

century, there were forty public baths within Damascus, and

another seventeen in its suburbs.[58]

Two centuries before him, the geographer al-Muqaddasi, when in

the city, exclaimed:

‘There are no baths more beautiful, no fountains more

wonderful.’[59] In his time, water was

piped from the

The baths were built on the traditional plan: a

vestibule for undressing followed by a number of rooms, each of

which was hotter than the other serially, and finally a cooler

one for re-adjustment to the external temperature.[66] Writing early in the

14th century, the Egyptian Ibn al-Ukhuwwa describes

the bath as having three chambers:

‘The

first chamber is to cool and moisten, the second heats and

relaxes, the third heats and dries.’[67]

The baths and the supply tank had to be thoroughly

cleaned every day.[68]

Like most aspects of Islamic civilisation, baths had

an intricate link with the faith, while the medieval Christians

forbade washing as a heathen custom. Lane Poole notes:

‘The

monks and nuns boasted of their filthiness, insomuch that a lady

saint recorded with pride the fact that up to the age of sixty

she had never washed any part of her body, except the tips of

her fingers when she was going to take the mass. While dirt was

characteristic of Christian sanctity, the Muslims were careful

in the most minute particulars of cleanliness, and dared not

approach their God until their bodies were purified.’[69]

The elimination of Islam from

‘Of the scandal the sight of apartments devoted to ablution and luxury

caused every good Christian, as well as for the reason that

their use was always considered entirely superfluous in a

monastic institution.’[71]

Philip II (1527-1598) ordered the destruction of all

public baths on the ground that they were relics of infidelity.[72]

Recurrently measures were

passed that all baths, public and private were to be destroyed,

and that no one in future was to use them.[73]

As an earnest enforcement, all baths were forthwith destroyed,

commencing with those of the king.[74]

Everyone clean and neat gave

the suspicion of being a Muslim who regularly performed their

‘ablutions'.[75]

One, Bartolome Sanchez, appeared in the Toledo

Auto da fe of 1597 for

bathing, and although overcoming torture, he was finally brought

to confess and was punished with three years in the galleys, and

perpetual prison and confiscation.[76]

Michael Canete, a gardener, for washing himself in the fields

while at work, was tried in 1606: there was nothing else against

him but he was tortured.[77]

Marcais insists that it is entirely erroneous to

believe that the Muslims released their used waters, sewage, or

refuse to the street.[78]

This is another prevailing stereotype in most writing on Islamic

medieval cities. Sanitary regulations were, in fact, maintained

to a high degree, and a thorough system of drainage prevailed.

Seven centuries after the cities of Spain had been drained by a

system of great sewers, their streets kept free from rubbish,

and subjected to daily cleansing, Scott observes, Paris was

still worthy of its ancient appellation of Lutetia, "The Muddy;"

the way of the pedestrian was blocked by heaps of steaming offal

and garbage; and droves of swine, the only scavengers, roamed

unmolested through court-yard and thoroughfare.’[79]

Sewage systems under the city of

Central in the provision and

upkeep of all such works and structures were strictly Islamic,

religious endowments, waqfs. The provision of drinking

water, which as noted, was considered a meritorious action,

resulted in many individuals building qanats and constituting

them into waqfs, whether in a town, or a particular quarter of a

city.[86]

In

And once more, the role of the

Muhtasib, the State Inspector, comes to the fore. Drinking water

in the towns came under his general supervision, and if water

conduits were in a state of disrepair, it was his duty to have

them repaired, and under certain situations could order the

townspeople to do so, and if the source of drinking water was

fouled, he could order them to rectify the matter.[90]

Health and social issues, equally, in both their

foundation, management and upkeep, were the result of strictly

Islamic forms of organisation, especially religious endowments,

complemented by measures from the central authority. The latter

was heavily involved in the construction and setting up of

hospitals and hostels, for instance.[91]

One of the earliest hospitals was established in old

Order and security in the Islamic city, finally, were

early imperatives, too. All cities had a police force, in

[1]

A.L. Udovitch; Urbanism; op cit; p. 310.

[2]

Z. Oldenbourg: The Crusades; op cit; p. 476.

[3]

F.B. Artz: The Mind; op cit; pp.148-50.

[4]

Ibid.

[5]

Ibid.

[6]

Ibn Jubayr

: The Travels of Ibn Jubayr; translated from the original Arabic with

introduction and notes, by R.J. C. Broadhurst (Jonathan

cape, London, 1952), p. 256.

[7]

M.Lombard: The Golden; op cit; p. 140.

[8]

Ibid.

[9]

F.B. Artz: The Mind; op cit; pp. 148-50.

- I. R and L.L. al Faruqi: The Cultural Atlas of Islam

(Mc

Millan Publishing Company New York, 1986), p 319.

-W. Durant: The Age of Faith; op cit; p. 302.

-R. Hillenbrand: Cordova: The Dictionary of the

Middle Ages; op cit; vol 3; pp 598-601.

[10]

F.B. Artz: The Mind; op cit; pp. 148-50;-

al Faruqi: The Cultural Atlas, p 319;

W.Durant: The Age of Faith; op cit; p. 302;

R.Hillenbrand: Cordova; op cit.

[11]

Rawd al-Qirtas in T.Burckhardt: Fez City of Islam

(The Islamic Text Society; Cambridge; 1992), p.73.

[12]

W. Durant: The Age of Faith; op cit; p. 208.

[13]

C. Dawson: Medieval Essays (Sheed and Ward:

London;

1953), p. 220.

[14]

F.B. Artz: The Mind; op cit; pp. 148-50;

Al- Faruqi: The Cultural Atlas, p 319; W.

Durant: The Age of Faith; op cit; p.

302.R.Hillenbrand: Cordova; op cit.

[15]

F.F. Armesto: Millennium (A Touchstone Book; New

York; 1995), pp. 97-9.

[16]

Ibid.

[17]

Ibid.

[18]

J. Lassner:

[19]

Ibid; pp. 642-3.

[20]

T. Glick: Islamic and Christian; op cit; p. 111.

[21]

Ibid; p.115-6.

[22]

Ibid.

[23]

K.Sutton-S.E. Zaimeche (1992) ‘Water

resource problems

in

S.E Zaimeche (1991): ‘Feeding the population in semi arid

lands: An assessment of the conditions of three North

Africa

n countries:

[24]

I.M. Lapidus: Muslim Cities in the Later Middle Ages,

(Harvard University Press; Cambridge Mass; 1967), p.

69.

[25]

Ibid; p. 70.

[26]

D.R. Hill: A History of Engineering in Classical and

Medieval Times (Croom Helm; 1984), p. 31.

[27]J.

Lassner:

[28]

Ibid; pp. 643.

[29]

G. Wiet et al: History; op cit; p.317.

[30]

F.B. Artz: The Mind; op cit; 148-50.

[31]

A.A. Duri:

[32]

D.R. Hill: A History of Engineering; op cit; p.

31.

[33]

Ibid.

[34]

This was the arrangement in many cities such as Zaranj

in Sijistan, and Nisbin in northern

[35]

I.M. Lapidus:

[36]

Ibid.

[37]

Z. Oldenbourg: The Crusades; op cit; p. 476.

[38]

G. Wiet et al: History; op cit; at .p.316.

[39]

Al-Istakhri: Kitab Masalik wal-Mamlik; ed. De

Goeje (

[40]

Ibid; p. 140.

[41]

Ibid; p. 216.

[42]

Al-Yaqubi: Kitab al-Buldan; ed. De Goeje (

[43]

Al-Muqaddasi: Ahsan al-Taqasim; (De Goeje ed) op

cit; p. 74.

[44]

M. Brett: Marrakech

in Dictionary

of the Middle Ages; op cit; vol 8; pp 150-1.

[45]

H. Ferhat:

[46]

Ibid.

[47]

W. Spencer: the Urban Achievements in Islam: Some

Historical considerations; in Proceedings of the

First International Symposium for the History of Arabic

Science (

[48] G. Marcais: l’Urbanisme; op cit; p. 226.

[49]

Al-Bakri in G. Marcais: l’Urbanisme; op cit; p. 226.

[50]

J. Lehrman: Gardens

; Islam; in The

[51]

S. Lane-Poole: The Moors in

[52]

S.P. Scott: History; vol 3; op cit; p. 520.

[53]

Ibid; vol 2; p. 601.

[54]

A. Bir: The Book of Kitab al-Hiyal of Banu Musa Bin

Shakir (IRCICA; Istanbul; 1990).

[55]

Z. Oldenbourg: The Crusades; op cit; p. 476.

[56]

D.R. Hill: A History of Engineering; op cit; p.

44.

[57]

Z.

Oldenbourg: The Crusades; op cit; p. 476.

[58]

Referred to by Thierry Bianquis: Damas in Grandes

Villes Mediterraneenes; op cit; pp. 37-55; at

p. 46.

[59]

Al-Muqaddasi: Ahssan al-taqassim; op cit; p. 157.

[60]

Al-Istakhri: Kitab al-masalik wa’l Mamlik;

ed. M.G. al-Hini (

[61] T. Bianquis: Damas; op cit; p. 46.

[62]

Ibn Shadad: Al-Alaq al-Khatira; Ed D. Sourdel (

[63]

W. Spencer: the Urban Achievements; op cit; p. 259.

[64]

S.P. Scott: History; op cit; vol 3; pp

520-2.

[65]

S.M. Imamuddin: Muslim; op cit; p. 208.

[66]

Ibid; p. 209.

[67]

Ibn Al-Ukhuwwa: Ma’alim al-Qurba fi Ahkam al-Hisba;

ed R. Levy; Arabic text with abridged English

translation (Gibb Memorial Series) (London; New Series;

1938), pp. 149 ff.

[68]

D.R. Hill: A History of Engineering; op cit; p.

44.

[69]

S. Lane Poole: The Moors; op cit; pp. 135-6.

[70]

T.B. Irving: Dates, Names and Places: The end of Islamic

Spain; in

Revue d'Histoire Maghrebine; No 61-62 (1991); pp

77-93; p.85.

[71]

S.P. Scott: History; op cit; Vol II, p.261.

[72]

S. Lane Poole: The Moors; op cit; pp. 135-6.

[73] Luis del Marmol Carbajal: Rebelion y castigo de los Moriscos de Granada

(Bibliotheca de autores espanoles, Tom.

XXI). pp.

161-2.

[74]

H. C. Lea: A

History of the Inquisition

of

[75]

T.B. Irving: Dates, names and places; op cit; p.81.

[76]

H.C. Lea: The Moriscos of Spain; Burt Franklin;

[77] Ibid.

[78] G. Marcais: l’Urbanisme; op cit; p. 226.

[79]

S.P. Scott: History; op cit;

vol 3; pp 520-2.

[80]

Ibid; vol 1;

p. 613.

[81]

M. Acien Almansa and A. Vallejo Triano: Cordoue; op cit;

p. 126.

[82]

Z. Oldenbourg: The Crusades; op cit; p. 498.

[83] G. Marcais: l’Urbanisme; op cit; p. 227.

[84]

G. Wiet et al: History; op cit; p.318.

[85] G. Marcais: l’Urbanisme; op cit; p. 226.

[86]

A.K.S. Lambton: Ma’; in Encyclopaedia of Islam;

op cit; vol 5; new series; at p. 876.

[87] S. Denoix: Bilans in Grandes Villes; op cit; p. 294.

[88] A.K.S. Lambton: Ma’; op cit; p.

876.

[89] Abd al-Husyan Sipinta: Tarikhiya-yi awkaf-I Isfahan; 1967; p. 360 in

A.K.S. Lambton: Ma’; op cit; p. 876.

[90]

R. Levey: The Social Structure of Islam (

[91]

A.M. Edde:

[92]

A. Whipple: The Role of the Nestorians and Muslims in

the History of Medicine; facsimile of the original

book, produced in 1977 by microfilm-xerography by

University Microfilms International (Ann Arbor,

Michigan, U.S.A; 1977), p. 93; and A Issa Bey:

Histoire des hopitaux en Islam; Beirut; Dar ar ra’id

al’arabi; 1981; pp. 112-5.

[93]

A Issa Bey: Histoire; op cit; pp. 112-5.

[94]

S. Denoix: Bilans, in Grandes Villes Mediterraneenes;

op cit; p. 294.

[95]

Ibid.

[96]

A.M. Edde:

[97]

Ibid.

[98]

A. Whipple: The Role; op cit; p. 80.

[99]

Ibid.

[100]

Ibid; p. 81.

[101]

A.M. Edde:

[102]

Ibid.

[103]

S. Denoix: Bilans; op cit; p. 294.

[104] D. Behrens Abouseif; S. Denoix, J.C. Garcin: Cairo

: in Grandes Villes; op cit;

p. 194.

[105]

Ibid.

[106]

S. Denoix: Bilans; op cit; p. 287.

[107]

Ibid.

[108]

Ibid.

[109]

M. Sakly: Kairouan in Grandes Villes Mediterraneenes;

op cit; pp. 57-85; p. 73.

[110]

Ibid.

[111]

T. Glick: Islamic;

op cit; p. 115. S.P. Scott: History; op

cit.

[112]

M. Acien Almansa and A. Vallejo Triano: Cordoue; op cit;

pp 117-34; at p. 128. |