Construction Skills, Aesthetics, and Historical Misrepresentations

‘It is only necessary to go through

the literary and artistic works of the Arabs,’ [says Le Bon] ‘to

notice that they always sought to embellish nature. The

characteristic of Arabic art is imagination, the brilliant,

splendour, exuberance in decoration, fantasy in the details. A

race of poets- and poets doubled with artists. Having become

rich enough to achieve all their dreams, they bred those

fantastic palaces which seem to be sculptures of marbles

engraved with gold and precious metals. No other people has

possessed such marvels, and none will ever posses them. They

correspond to an age of youth and illusion gone for ever. It is

not this epoch of cold and utilitarian banality, which humanity

has now entered where they could be sought.’[1]

The same impression

conveyed by Talbot Rice:

‘The Period of Samarra’s supremacy (836-83), so far as art was

concerned, was one of the most brilliant in Islamic history; at

no time before had so much been built in so short a space of

time or had such elaborate decorations been devoted to so large

a number of houses as well as mosques and palaces. As one

wanders over this immense field of ruins one can but marvel at

the age which was responsible for such lavishness.’[2]

Madinat al-Zahra (in Cordova) is mesmerizing in

Scott’s words:

‘From a

royal villa,

There is a

specialised Western literature in praise of Islam’s construction

skills and aesthetic accomplishments seen in buildings such as

the Great Mosque

of Damascus

, The Dome of the Rock in

Mainstream Western literature dealing with Islamic

history and civilisation, however, offers a completely

different, derogatory picture, and tends to paint Muslims, some

dynasties, in particular, as wholly incapable of any

construction or architectural skills. The Seljuks

are amongst the dynasties that

have been brutalised by nearly all Western historians. Hence,

Ashtor, supposedly a leading expert on Islamic cultural, social

and economic history, devotes a considerable proportion of his

work lashing out at every aspect of the Seljuk history. In

relation to their (lack of) construction skills, he says, for

instance:

‘The

attentive reader of the Arabic chronicles of the Seljukid age

becomes aware of these facts at time and again he comes across

reports of bridges falling down and dams bursting. For often the

chronicler reveals that it was not simply the consequence of

negligence but of bad construction and ineffective repairs.’[6]

A general picture of Seljuk ineptness in the field is

shared by mainstream historians.[7]

Looking at historical evidence, however, once more,

fundamentally contradicts this picture. During the crusades, the

Seljuks

were always prompt to repair any

damaged structures, whether in time of peace or war, at

‘Such

monuments laugh out of court the notion that the Turks

were barbarians. Just as the

Seljuk rulers and viziers were among the most capable statesmen

in history, so the Seljuk architects were among the most

competent and courageous builders of an Age of Faith

distinguished by massive and audacious designs. The Persian

flair for ornament was checked by the heroic mood of the Seljuk

style; and the union of the two moods brought an architectural

outburst in Asia Minor, Iraq

, and Iran

, strangely contemporary with the Gothic flowering in France.’[17]

Also in praise of Seljuk achievements is Talbot Rice,

who says:

‘Though

every part of the Islamic world was responsible for the

production of works of art of every type, there seem, as we look

back today, to be certain especially outstanding arts that we

can associate with particular areas or ages; glass with Syria

, pottery and miniatures with Persia

, or metalwork with modern Mesopotamia, for example, and if we were to

follow up this line of thought it would be certainly

architecture and architectural decoration that we would

associate with the Seljuk of Rum. All over Asia Minor there

survive to this day a mass of mosques and madrasas in a very

distinctive style and boasting decorations either in carved

stone or tile work which are among the finest in all Islam.’[18]

Talbot Rice notes how the Seljuks

were the first to develop fine

buildings planned as caravanserais, some of which were of

considerable size, some almost palaces, and their architecture

of the finest sort.[19]

Other Islamic ethnic groups, Mamluks

and Berbers

, above all, are also presented by the majority of Western historians as

lacking in skills and care for aesthetics.[20] This, once more, is

contradicted by evidence. The Mamluk legacy, for instance,

continued to influence Islamic art up to the 20th

century.[21] In their time (mid 13th

century onward), they erected hundreds of religious and secular

edifices in

Berber accomplishments, which

will form a major part of discussion in the final part of this

work, although generally denied were equally obvious. They

can be seen in the 12th century, both in

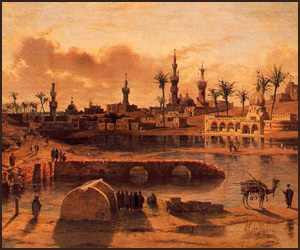

It is common to find in most Western literature a

countless amount of adverse assertions such as that Islamic

buildings hardly rose above one floor due to lack of engineering

skills, or that their interiors lacked in innovativeness, or

that they neglected their immediate surroundings. Instances

given under previous headings contradict this picture, and need

not be repeated. Briefly here, in relation to some such

arguments, evidence from

medieval Al-Fustat (old

[1] G Le Bon: La Civilisation; op cit; p. 402.

[2]

D. Talbot Rice: Islamic Art (Thames and Hudson;

London; 1979 ed), p. 97.

[3]

S.P. Scott: History; op cit;

vol 1; p. 630.

[4]

See for instance:

-K.A.C. Creswell: Early Muslim Architecture

, 2 Vols (1932-40).

-E. Male: Art et artistes du Moyen Age

(Paris 1927), pp. 30-88.

-G. Marcais: Manuel d’Art Musulman (Paris;

1926).

-G. Marcais:

l'Architecture

Musulmane

d'Occident, Paris 1954.

-H. Terrasse: L’Art hispano mauresque des

origins au 13em siecle (Paris; 1933).

[5]

K.A.C. Creswell: A Short Account on early Islamic

Architecture

(Scholar

Press; 1989).

[6]

E. Ashtor: A Social and Economic History of the

[7]

G. Wiet et al: History; op cit; pp. 7; 156-7; 243

etc. F.B. Artz: The Mind; op cit; p. 175-6; D.

Campbell: Arabian Medicine; op cit; etc (see also

final part, the section on Orthodoxy).

[8]

M. Erbstosser: The Crusades; op cit; p. 123

[9]

J. Harvey: The Development of Architecture

, in The Flowering of the Middle Ages; ed J. Evans (Thames and

Hudson; 1985), pp. 85-106.

[10]

F.F. Armesto: Millennium (A Touchstone Book; New

York; 1995), pp. 97-9.

[11]

Ibid.

[12]

Ibid.

[13]

Ibid.

[14]

W. Durant: The Age of Faith; op cit; pp. 316-7.

[15]

Ibid.

[16]

Ibid.

[17]

Ibid; pp. 317.

[18]

D. Talbot Rice: Islamic Art; op cit; p. 165.

[19]

Ibid; p. 165-6.

[20]

Such as:

-C. Brockelmann: History of the Islamic Peoples

(Routledge; London; 1950).

- E. Ashtor: A Social and Economic History; op

cit.

[21]

E. Atil: Mamluk art: Dictionary of Middle Ages;

op cit; Vol

8; p. 69.

[22]

Ibid; pp. 69-70.

[23]

Ibid.

[24]

Ibid.

[25]

D. Talbot Rice: Islamic Art; op cit; p. 149.

[26]

A. Chejne: Muslim

[27]

Ibid.

[28]

Ibid; p. 368.

[29]

D. Talbot Price: Islamic Art; op cit; p. 149.

[30]

G. Wiet et al: History; op cit; pp 317-8.

[31]

S.P. Scott: History; op cit;

vol 3; pp 520-2.

[32]

G. Wiet et al: History; op cit; p.317.

[33]

Ibid; p.318. |