Early Islamic Passion for Gardens

and Gardening and its

Source

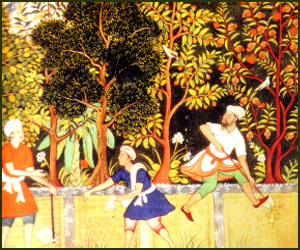

In the words of garden historians, the inhabitants of

the early Islamic world were, to a degree that is difficult to

comprehend today, ‘enchanted by greenery’.[1]

In ‘a civilisation, which thought of itself as a garden,

gardening was naturally an esteemed art,’ notes Armesto.[2]

‘In a

mountain of lush greenery,’ [says Marcais,] ‘Nature

finds its home. Here, no place

for vegetal mosaics laid on the ground as in

Scott describes how the Muslims:

‘Introduced on a diminished scale the hanging gardens of

From the far eastern parts, on the frontiers with

‘Devotion, if not mania’ for pretty flowers, was prevalent

everywhere, and in their multitude; fondness for tulips in 16th

century

Further to the West, Al-Fustat, Old Cairo

, with its multi-storey dwellings, had thousands of private gardens,

some of great splendour.[13]

‘The

New Kiosq is a palace in the midst of two gardens. In the centre

was an artificial pond of tin (or lead), round which flows a

stream in a conduit, also of tin, that is more lustrous than

polished silver…. All around this tank extended a garden with

lawns with palm trees… four hundred of them… The entire height

of those trees, from top to bottom was carved in teakwood,

encircled with gilt copper rings. And all these palms bore full

grown dates, which in almost all seasons were ever ripe and did

not decay. Round the sides of the garden also were melons… and

other kind of fruit.’[19]

Equally stunned by the eastern greenery were the

incoming crusaders (1095-1291). Dreesbach notes that the

passages from the French literature of the crusading period,

which describe the Orient, show that the things which impressed

themselves on the minds of historian, chronicler and poet were

the richness of gardens and orchards and the fertility of the

fields.[20] Thus, William of

Tyre’s History goes:

‘The

plain of Antioch are full of many rich fields for the raising of

wheat and abounding in springs and rivulets.’[21]

And on the neighbourhood of

‘There

are great number of trees bearing fruits of all kinds and

growing up to the very walls of the city and where everybody has

a garden of his own.’[22]

Crossing into North Africa

, where Islamic gardens

appeared in the 9th century,

[23]

one

learns of a multitude of gardens, surrounding and inside cities

such as

In Spain, writers speak endlessly of the gardens and

lieux de plaisance of Seville

, Cordova and Valencia

; the suburb of Valencia having so many orchards and flower gardens that

the city looked like a maiden in the midst of flowers, the scent

of which perfumed the air;[33] the city was called by

one writer ‘‘the scent bottle of al-Andalus.’[34]

Market gardens, olive groves, and fruit orchards made some areas

of Spain-notably around Cordova,

Like every science, and like every single aspect of

Islamic civilisation, behind the passion and devotion to gardens

and gardening, natural beauty and greenery, was the faith,

Islam, and its central element, the Qur’an. Thus, we read in the

Qur’an:

‘Surely

the God fearing shall be among gardens and fountains.’ (Qur’an

51/15).

‘And

those on the right hand; what of those on the right hand?

Among

thornless lote trees

And

clustered plantains,

And

spreading shade,

And

water gushing,

And

fruit in plenty

Neither

out of reach nor yet forbidden,

And

raised couches.’ (Qur’an 56/27-34)

And equally:

‘But

for him who feareth the standing before his Lord there are two

gardens.

Which

is it, of the favours of your Lord, that ye deny?

Of

spreading branches.

Which

is it, of the favours of your Lord, that ye deny?

Wherein

are two fountains flowing.

Which

is it, of the favours of your Lord, that ye deny?

Wherein

is every kind of fruit in pairs.

Which

is it, of the favours of your Lord, that ye deny?

Reclining upon couches lined with silk brocade, the fruit of

both gardens near to hand.

Which

is it, of the favours of your Lord, that ye deny?

Therein

are those of modest gaze, whom neither man no jinni will have

touched before them.

Which

is it, of the favours of your Lord, that ye deny?

(In

beauty) like the jacinth and the coral stone.

Which

is it, of the favours of your Lord, that ye deny?

Is the

reward of goodness aught save goodness?

Which

is it, of the favours of your Lord, that ye deny?

And

beside them are two other gardens.

Which

is it, of the favours of your Lord, that ye deny?

Dark

green with foliage.

Which

is it, of the favours of your Lord, that ye deny?

Wherein

are two abundant springs.

Which

is it, of the favours of your Lord, that ye deny?

Wherein

is fruit, the date palm and pomegranate

Which

is it, of the favours of your Lord, that ye deny?

Wherein

(are found) the good and the beautiful-

Which

is it, of the favours of your Lord, that ye deny?

Fair

ones, close guarded in pavilions-

Which

is it, of the favours of your Lord, that ye deny?

Whom

neither man nor jinni will have touched before them-

Which

is it, of the favours of your Lord, that ye deny?

Reclining on green cushions and fair carpets.

Which

is it, of the favours of your Lord, that ye deny?

Blessed

be the name of thy Lord, Mighty and Glorious.’

(Qur’an

The expression: ‘Gardens

underneath which rivers flow’ is

the most repeated expression in the Qur’an (thirty seven times)

for ‘the bliss of the faithful.’[43]

Picturesque as the Qura’nic descriptions of the heavenly garden

may be,’ Shimmel holds, ‘we can only imagine what it may be

like.’ Sura 57/21 specifies its extension:

‘And a

Garden the breadth whereof is as the breadth of heaven and

earth…’

and sura (77/41):

‘…Shades and fountains and such fruits as their hearts desire.’

Descriptions of the heavenly garden, which Schimmel

explains, are consistent and give an impression of greenery and

gushing fountains.[44]

Faith and greenery also predominate in the words of

poets, here the Egyptian Dhu’n-Nun (d.859):

‘O God,

I never hearken to the voices of the beasts or the rustle of the

trees, the splashing of the waters or the song of the birds, the

whistling of the winds or the rumble of the thunder, but I sense

in them as testimony to Thy Unity, and a proof of Thy

incomparableness, that Thou art the All Prevailing, the All

Knowing, the All True.’[45]

Yunus Emre, the medieval mystic of Anatolia, in a

little poem, describes

‘Sol cennetin irmaklari

Akar Allah deyu deyu…..

The

rivers all in paradise

Flow

with the word Allah, Allah,

And

every longing nightingale

He

sings and sings Allah, Allah;

The

branches of the Tuba tree

The

tongue reciting the Qur’an,

The

roses there in

Their

fragrance is Allah, Allah…’[46]

Garden historians were prompt to see such connections

between faith and the early Islamic passion for gardening.[47]

When a whole people can

anticipate the paradise of afterlife as a garden, there can be

little doubt about their enthusiasm for gardens on aesthetic

grounds and still less doubt about their high significance in

the every day life of those times, says Cowell.[48]

Ettinghausen, too, notes that:

‘If the

garden was such a ubiquitous art form in the Muslim world, being

both socially and geographically extensive, there must have been

specific reasons for this propensity…’ and first comes ‘the idea

of Paradise as a reward for the Muslim faithful,’ a garden,

descriptions of which have ‘played an important part in the

Muslim cosmography and religious belief.’[49]

Early Muslims everywhere, Watson holds, ‘made earthly

gardens that gave glimpses of the heavenly garden to come.’[50]

Every garden was meant to be a little paradise as Ettinghausen

put it ‘for the happy owner’ carefully protected from the hustle

and bustle of the city and its odours.[51]

The spread of Islam saw many gardens established, since not only

did they provide climatic relief in those parts of the world,

but they granted foretaste of the reward promised to the

faithful, as well as a less spiritual but attractive reflection

of the traditional royal-pleasure garden.[52]

And the earthly visions of Paradise have inspired the

construction of gardens; rivers flowing through paradise helping

architects to conceive the canals as they flow through the

gardens, each part of the garden being in some way a similitude

of Paradise.[53]

Literary and archaeological sources find origins of

gardens as early as the 730s, and stretching to the whole

Islamic world.[54]

In laying out and ornamenting gardens, kings and nobles, rich

and poor, theologians and laymen, all participated with equal

zeal and enthusiasm and, as a result, each villa, each palace

and each town was a delight to the eye.[55] Rulers in the days of

Islam, when not versed into scholarly passion, were equally

passionate about their gardens; they and their surrounding

elites laying out their beautiful gardens in palaces for

recreation both on river bank and in mountain valleys and on

mountain tops, supplying them with water in abundance.[56] Some such gardens had

great splendour, and their renown went beyond their territory,

such as al-Mu'tasim’s gardens at Samarra, Iraq

;[57]

the great royal parks of the Aghlabid emirs of Tunisia

, near Al-Qayrawan

, the famous garden of the Hafsid rulers, also in Tunisia;[58] and the gardens

surrounding the royal palaces at Fez and Marrakech

.[59]

In Cairo

the Mamluk sultan Qalawun

(Qala’un) introduced Syrian plants into his garden in great

variety,[60] whilst Rumarawayh, a

Tulunid ruler in the later 9th century, had in his

garden palm trees, whose trunks were covered with gold; behind

this covering were pipes which brought water up the side of the

trees and sprayed it out from various openings into pools.[61] In the

This passion for gardening extended to the population

at large, the Muslims using the art of planting to beautify

their homes and countryside.[67]

Ettinghausen notes how there were even carefully planned mini

gardens with trees, bushes, flowers and central water basins and

fountains in the courtyards of countless private homes, owned by

men of very limited means.[68]

At Fustat, in old

‘Love

of flowers was a veritable passion among the Spanish Moslems. As

they were the greatest botanists in the world, so no other

nation approached them in the perfection of their floriculture

and the ardour with which they pursued it. The profusion and

variety of blossoms of every description were marvellous and

enchanting; each had a meaning, by which tender sentiments could

be conveyed without the instrumentality of speech; they were

associated with every public ceremony and with the most prosaic

occurrences of domestic life; they dispensed their fragrance

from the priceless vase of the palace; they covered the cottage

of the labourer; they formed the daily decoration of the

luxuriant tresses of the princess and the peasant; their

garlands were the common playthings of the infant.’[71]

Amidst greenery was also found genial creativity. The

Muslims, Gothein says, liked artificial culture, different

fruits on one tree; different grapes on one vine, which they

thought specially pleasing, and they liked to have flowers of

unnatural colours, and to graft a rose upon an almond tree.[72]

In the Tulunid garden (9th century

The garden, a symbol of the promised paradise, has,

thus, become a little earthly paradise in itself. For the early Muslim,

lengthy contemplation of such beauty was enough to replenish

life and chase away its sorrows and stresses. An owner would

take delight in his garden more by sitting on a rug and cushions

in contemplation of his pavilion, than by walking through it.[80]

In front of his palace Rumarawayh, the Tulunid ruler of

Egypt

(r. 884-896), built a pool of

50x50 cubits filled with mercury on which he floated on an air

mattress to cure his insomnia; it was reported to be spectacular

by moonlight. And to enjoy his view, Rumarawayh even built a

domed kiosk in his palace overlooking the bustan (garden) and

the city.[81]

There, inside his artificial

Spanish paradise-the site of Soto de Rojas famous poem[82]

could have been chosen by an Arab-he could enjoy in solitude the

voluptuous pleasure produced by different perfumes, colours and

shapes in endlessly varied combinations: in sum, it was

a place where the refined sensuality of the Muslim

sensibility could find full and perfect expression, says Dickie.[83]

‘It is from this quiet scene of beauty found in the Arabian

court garden,’ Gothein concludes, ‘that their poetry takes its

beginning.’[84]

[1] D. Sourdel: Baghdad

: Capitale du Nouvel empire

Abbaside; Arabica ix (1962; pp. 251-65. D.

Goitein: A Mediterranean

Society; op cit; J. Sourdel Thomine:

La Civilisation de l’Islam (Paris; 1968), J.

Dickie: Nosta Sobre la jardineria arabe en la espana

Musulmane; Miscelanea de estudios arabes y hebraicos

XIV-XV (1965-6); pp 75-86. G. Marcais: Les Jardins

de l’Islam; in Melanges d’Histoire et d’archeologie

de l’occident Musulman; 2 Vols (Alger; 1957), pp

233-44;

[2]

F.F Armesto: Millennium; A Touchstone

Publication, (Simon and Shuster New York; 1995), p.35.

[3] G. Marcais: Les Jardins; op cit; p. 240.

[4]

S. P. Scott: History; op cit; vol 2;

p. 605.

[5]

A. Watson: Agricultural, op cit, p.117.

[6]

Z. Oldenbourg: The Crusades; op cit; p. 476.

[7]

D.R. Hill: A History of Engineering in Classical and

Medieval Times (Croom Helm; 1984), p. 26.

[8]

F.R. Cowell: The Garden as a Fine Art (Weidenfeld

and Nicolson; London; 1978), p. 72.

[9]

Ibid.

[10]

Ibid.

[11]

D.R. Hill: A History of Engineering; op cit; p.

26.

[12]

R. Ettinghausen: Introduction; in The Islamic Garden,

Ed by E.B. MacDougall and R. Ettinghausen (Dumbarton

Oaks; Washington; 1976), p.5.

[13]

G. Wiet:

[14]

J. Lehrman: Gardens

; Islam; in The

[15]

Al-Duri: Tarikh al-Iraq

(

[16]

Yaqut: Muaajam; op cit; vol iv; p. 787.

[17]

In R. Ettinghausen: Introduction; op cit; p. 3.

[18]

M.L. Gothein: A History of Garden Art (Hacker Art

Books; New York; 1979), pp. 146-8.

[19]

E. Herzfeld: Mitteilungen uber die Arbeiten der zweiten

Kampagne von Samarra,’ Der Islam 5 (1914); 198.

[20]

Dreesbach: Der Orient; 1901; pp. 24-36. In J.K. Wright:

The Geographical Lore of the Time of the Crusades

(Dover Publications; New York; 1925), p. 238.

[21]

Historia; IV; 10; Paulin Pari’s edit.; vol I; pp. 134-5

in J. K. Wright: The Geographical Lore; p. 239.

[22]

Historia; XVII, 3; Paulin Pari’s edit.; vol ii; p. 141

in J. K. Wright: The Geographical Lore; p.

239.

[23] J. Lehrman: Gardens

; Islam;

op cit; p. 279.

[24] Torres Balbas: La Ruinas de Belyunes o Bullones; Hesperis Tamuda v

(1957) 275-96; 275 ff; G. Marcais: les Jardins de

l’Islam; op cit.

[25]

J. Lehrman: Gardens

; op cit; p. 279.

[26]

Ibid.

[27]

Leon The African in G. Marcais: les Jardins; op cit; p.

241.

[28] J. Lehrman: Gardens

; Islam;

op cit; p. 279.

[29] In G. Marcais: Les Jardins; op cit; p. 241.

[30]

A. Solignac; p. 382; in A.M. Watson: A Medieval Green

Revolution; op cit; Note 44; p. 56.

[31]

S. Soucek:

[32]

Ibid.

[33]

S.M. Imamuddin: Muslim

[34] Al-Maqqari: Nafh al-Tib; op cit; vol I; p.67;

H. Peres: La Poesie Andaluse en Arabe

Classique au Xiem siecle (Paris; 1953), pp. 115ff.

[35]

W. Durant: The Age of Faith; op cit; p. 298.

[36]

Al-Maqqari in E. Hyams: A History of Gardens

and Gardening

(J.M. Dent and

Sons LTD; London; 1971); p. 82.

[37]

Al-Maqqari: Nafh al-Tib; op cit; pp. 211-2.

[38]

J. Harvey: Medieval Gardens

; op cit; p. 38.

[39]

Al-Maqqari: Nafh al-Tib; vol I; I; pp. 57-8.

[40]

W. Durant: The Age of Faith; op cit; p. 298.

[41]

S.P. Scott: History; op cit; vol 2;

614.

[42]

Al-Maqqari: Nafh al-Tib;

II; p. 360; n. 12.

[43]

A.Schimmel: The Celestial garden in Islam; in The

Islamic Garden, op cit; pp 13-39; at p. 15.

[44]

Ibid; p. 17.

[45]

Ibid; p. 24.

[46]

Yunus Emre Diwani; ed A. Goplinarli (

[47] G. Marcais: Les Jardins; op cit; J. Dickie: Nosta Sobre la jardineria arabe

en la espana Musulmane; Miscelanea de estudios arabes

y hebraicos XIV-XV (1965-6); pp 75-86.

[48]

F.R. Cowell: The Garden as a Fine Art (Weidenfeld

and Nicolson; London; 1978), p. 75.

[49]

R. Ettinghausen: Introduction, op cit, at p. 6.

[50]

A.M. Watson: Agricultural; op cit; p.117.

[51]

R. Ettinghausen: Introduction; op cit; p. 7.

[52]

J. Lehrman: Gardens

; Islam; op cit; p. 278.

[53]

A.Schimmel: The Celestial, op cit; p. 15.

[54]

R. Ettinghausen: Introduction; op cit; p. 3.

[55]

S.M. Imamuddin: Muslim

[56] Ibid.

[57] H. Viollet: Description du Palais de al-Mutassim a Samarra; in Memoires

de l’Academie des Inscriptions et des Belles Lettres;

XII : 1913.

[58]A. Solignac: Recherches sur les installations hydrauliques de kairaouan et

des Steppes Tunisiennes du VII au Xiem siecle, in

Annales de l’Institut des Etudes Orientales, Algiers

, X (1952); 5-273. pp 218 ff; G. Marcais: Les Jardins; op cit; p. 237.

[59] G. Marcais: Les Jardins; op

cit; p. 237.

[60]

Al-Maqrizi, Ahmad Ibn Ali.

Al-Mawaiz wa Alitibar fi dhikr al-Khitat wa-Al-athar.

Edited by Ahmed Ali al-Mulaiji. 3 Vols, (Beirut: Dar al

Urfan. 1959), II; op cit; p. 119.

[61] Ibid; 96.

[62] M. Meyerhof: Sur un traite d’agriculture compose par un sultan Yemenite du

XIV em siecle; Bulletin de l’Institut d’Egypte;

xxv (1942-3) 54-63; xxvi (1943-4); 51-64; (1942-3) p.58;

and (1943-4) pp. 52; 57.

[63]

A. Watson: Agricultural, op cit, p.118.

[64]

S.M. Imamuddin: Some Aspects of the Socio-Economic

and Cultural History of Muslim

[65]

Al-Maqqari:

Nafh al-Tib;

ii: 14-5; H.Peres: Le Palmier en Espagne

Musulmane; In Melanges Geodefroy Demombynes

(Cairo

; 1935-45), pp. 224-39.

[66]

Al-Udhri: Nusus an al-Andalus; ed. Abd al-Aziz

al-Ahwani (

[67]

S.M. Imamuddin: Some Aspects;

op cit; p. 82.

[68]

R.Ettinghausen: The Islamic; op cit; p.5.

[69] G. Marcais: Les Jardins; op cit; p. 236.

[70]

Brunschvig, quoted in G. Marcais: Les Jardins; op cit;

p. 242.

[71]

S.P. Scott: History, op cit,

vol 2;

p.651.

[72]

M.L. Gothein: A History of Garden Art (Hacker Art

Books; New York; 1979), p. 150.

[73]

Ibid.

[74]

Ibid.

[75]

Ibid.

[76]

Ibid.

[77]

Ibid; p. 151.

[78]

Ibid.

[79]

J. Lehrman: Gardens

; Islam; op cit; p. 278.

[80]

Ibid.

[81]

Doris Behrens-Abuseif: Gardens

in Islamic

[82]

Parayso cerrado para muchos, jardines abiertos para

pocos ‘Paradise closed to many, gardens open to

few.’

[83]

J. Dickie: The Islamic Garden; op cit; in The Islamic

Garden (Ed by E.B. MacDougall and R. Ettinghausen)

op cit; pp. 87-106; p. 105.

[84]

M.L. Gothein: A History of Garden Art; op cit; p.

151. |