|

Greek Vs Islamic Astronomy

The assertion that Islamic

astronomy is a mere reproduction of Greek astronomy is

groundless as this chapter will abundantly show. Briefly are

considered here

some fundamental differences between Islamic and Greek

astronomy.

First, Muslim astronomers dealt with a considerable number of

subjects Ptolemy never addressed or contemplated, or could even

address or contemplate, all subjects, which are today the realm

of modern astronomy.

The briefest set of instances will show that it is not in

Ptolemy that one finds trigonometrical calculations relating to

this subject,[1]

nor the many calculations, findings, and theories that the

hundreds of Muslim astronomers made,[2]

nor the use of observation for scientific purposes.[3]

Ptolemy’s tables did not stand in comparison with Muslim tables,

such as al-Zarqali’s for instance.[4]

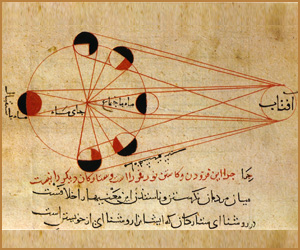

It was also the Muslims who initiated the greatest

breakthroughs in the issue of planetary theories, and not

Ptolemy or other Greek astronomers.[5]

Moreover, contrary to Ptolemy, Muslim astronomers such as

al-Sijzi (fl late 9th century) did conceive that the

earth was moving in its own axis.[6]

This is further confirmed by another astronomer of the 13th

century, Al-Harrani, who held ‘according to the geometers (or

engineers) (muhandeseens), the earth is in constant

circular motion, and what appears to be the motion of the

heavens is actually due to the motion of the earth and not the

stars.’[7]

Muslim astronomers, besides exploring issues never addressed by

Ptolemy, refuted him, and even ridiculed him.[8]

This will be made particularly obvious in the section dealing

with Andalusian astronomers.

The

second most important difference between Islamic and Greek

astronomy is that, unlike its Greek predecessor, Islamic

astronomy was not just the work of a handful of figures, in

fact, mainly a lone figure (Ptolemy), but literally that of

hundreds. Suter, early in the 20th century, listed

over 500 Muslim astronomers,[9]

a figure since augmented considerably by

Sarton[10]

and Sezgin.[11]

A recently published work by Rosenfeld and Ihsanoglu has made an

up-date of the works and accomplishments of hundreds of Muslim

astronomers whose scope was far reaching, and had considerable

influence on modern astronomy.[12]

Thirdly, Islamic astronomy was universal in its character, and

as to be seen below under Observation

, it generally involved teams of workers in specified tasks.

Illustrating this universal-team work character is the fact that

often, even members of the same family collaborated. The three

Banu Musa bothers, for instance, made observations and worked on

diverse scientific subjects in a collaborative effort.[13]

The same with Ibn Amajur, the father, who made observations

between 885 and 933, with his son Abu-l Hasan Ali and an

emancipated slave named Muflih.[14]

They were some of the greatest observers of Islam, father and

son, and Muflih, making many observations, and producing

numerous astronomical tables.[15]

There is also the mention of another member of the family, and

collaborators working with them.[16]

Fourthly, and more importantly, very early, Muslims astronomers,

like other Muslim scientists, insisted on the need not just for

observation and calculation, but also repeated verifications of

results. Briffault notes how Muslims compiled new sets of

planetary tables, and obtained more accurate values for the

obliquity of the ecliptic and procession of equinoxes, that were

checked by two independent measurements of a meridian the

estimates of the size of the earth.[17]

Al-Biruni

and Abu’l Wafa

(940-998), for instance, made in the year 997 arrangements to

observe the lunar eclipse of that year and compare notes; Abu’l

Wafa observing it in

Fifthly, instruments built by Muslim astronomers surpass

anything Greek astronomy did.[20]

Muslim astronomers, for

instance, defined their findings, and devised their astronomical

tables through observations and calculations, and using for the

first time sophisticated apparatus for such operations.[21]

Al-Battani

recommends for parallax

measurements the use of the large, or huge, quadrant and the

parallactic ruler.[22]

The following highlights further the points just made, and

dwells on the various Muslim accomplishments in the field.

[1]

See: A. Nallino:

Albateni Opus Astronomicum (Arabic text with Latin

translation), 3

vols (Milan 1899-1907 reprinted Frankfurt 1969).

G. Sarton: Introduction; op cit; vol 2, most

particularly.

[2]

H. Suter: Die

Mathematiker und Astronomen der Araber und ihre Werke

(1900; reprint APA, Oriental

Press,

[3]

A Sayili: The

Observatory

in Islam,

Turkish

Historical

Society (

B. Hetherington: A Chronicle of Pre-Telescopic

Astronomy (John Wiley and Sons; Chichester; 1996).

[4]

M. Steinschneider:

Etudes sur Zarkali;

Bulletino

Boncompagni; vol 20.

Notice sur les tables astronomiques attribuees a Pierre

III d’Aragon

(Rome, 1881).

[5]

J. North:

Astronomy and Cosmology (Fontana Press, London,

1994).

G. Saliba: Critiques of Ptolemaic astronomy in Islamic

Spain; in

Al-Qantara, Vol 20 (1999); pp 3-25.

[6]

G. Saliba: Al-Biruni

; in Religion, Learning

and Science in

the Abbasid Period;

Ed by M.J.L.Young; J.D. Latham; and R.B. Serjeant

(Cambridge University Press; 1990) pp. 405-23; p. 413.

[7]

Ahmad b. Hamdan al-Harrani: Kitab jami al-funun;

British Library; Ms Or..6299., fol. 64v.

[8]

See the following for an abridged outline of Islamic

destruction of Ptolemy’s astronomy by Al-Battani

in

P Benoit and F. Micheau: The Arab intermediary;

op cit; p. 203. by Al-Zarqali in P.K.Hitti: History

of the Arabs (MacMillan, London, 1970 ed),

p. 571.

by Al-Bitruji in A. Djebbar: Une Histoire;

op cit; p.194. by Jabir Ibn Afllah in F.Braudel:

Grammaire des Civilisations (Flammarion, 1987),

p.113. and

G. Sarton: Introduction;

op cit; Vol II;

p.18.

[9]

H. Suter: Die Mathematiker und Astronomen der Araber

(1900); op cit.

[10]

G. Sarton: Introduction; op cit.

[11]

F. Sezgin:

Geschichte des arabischen Schrifttums (vol vi for

astronomy); 1978.

[12]

B. Rosenfeld and E. Ihsanoglu: Mathematicians,

Astronomers and Other Scholars of Islamic Civilisation;

Research Centre for Islamic History, art and Culture;

[13]

D. Debagh: Banu Musa; in Dictionary of Scientific

Biography; Editor Charles C. Gillispie (Charles

Scribner's Sons, New York, 1970 ff). Vol 1; pp 443-6.

[14]

G. Sarton: Introduction; vol 1; op cit; p. 630.

[15]

E.S. Kennedy: A Survey of Islamic Astronomical Tables;

Transactions of the American Philosophical Society;

New Series; vol 46; part 2 (1956); pp. 125; 134; 135.

[16]

Ibn al-Qifti: Tarikh al-Hukama; op cit; pp.

220-1.

[17]

R. Briffault:

The Making, op. cit, p. 193.

[18]

Al-Biruni

: Tahdid Nihayat al-Amaqin li tashih Masafat

al-Masakin; Istanbul; Sulaymaniye Library;

Fatih-3386; p. 275.

[19]

A

Sayili: The Observatory

in Islam,

op cit; p.

27.

[20]

See, for instance,

A. L. Sedillot: Memoire sur les instruments astronomique

des Arabes,

Memoires de l’Academie Royale des Inscriptions et Belles

Lettres de l’Institut de France 1: 1-229 (Reprinted

Frankfurt, 1985).

[21]

See for instance:

A. L. Sedillot: Memoire; op cit;.

B. Hetherington: A Chronicle of Pre-Telescopic

Astronomy (John Wiley and Sons; Chichester; 1996).

R.P. Lorch: The Astronomical Instruments

of Jabir Ibn

Aflah and the Torquetom;

Centaurus,

(1976) vol 20; pp 11-34.

[22]

Al-Battani

: Kitab al-Zij al-Sabi; ed. A. Nallino (Roma;

1899-1907), in three vols; vol 1; p. 82. |