Arts

|

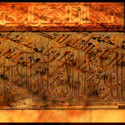

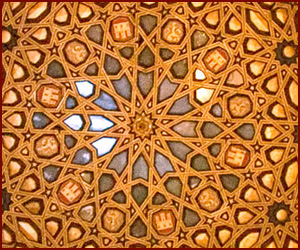

For over 1,300 years,’ Ettinghausen

says, `the worlds of Islam and of Europe have been in more or

less constant, dynamic relationship, and often tense

confrontation. But in spite of violent denigration of the Muslim

religion and its Prophet

(as seen in chapter

one), the West has had nothing but admiration for the arts of

the Near East. It manifested itself in the association of

whatever was available of this art with its most revered

institutions, whether sacred or mundane, and in artistic

borrowings of one type or another by the West from the East.’[1]

Not

everything, though, was borrowed from Islam. Far from it, in

fact. In Islamic art, there is no sanctified iconography of the

Prophet

of Islam paralleling

that of Christ, the Holy Family, and of the saints, within the

iconographic repertory of the Roman Catholic or the Greek

Orthodox Church.[2]

Besides, as Ettinghausen holds, Awn Ibn Abi-Juhayfah reported

that:

`The

Prophet

forbade men to take the

price of blood or the price of a dog, or the earnings of a

prostitute, and he cursed the tattooing woman and the woman who

had herself tattooed, the usurer, and the man who let usury be

taken from him, and he cursed the painter.'[3]

Hence the painter at the same level as usurer, and the earnings

of the prostitute. Everyone, on the other hand, knows the

elevated value of painting in Western culture.

The Islamic artistic influence on the Christian West did, however, take place, and in many aspects as the following outline will show. This influence is not, in fact, just purely artistic as most, if not all, previous studies have shown. Instead, it was crucial to the development of many early crafts and industries of Western Christendom , which aimed at reproducing Islamic objects and models. This is one of the main points that will be focused upon in this outline. Another point of focus, once more, is with regard to the patterns of influence, which repeat themselves, and are the same as other changes observed elsewhere. Before looking at these points, first it is looked at how Islamic art and aesthetics stimulated both admiration and artistic reproduction.

[1]

R. Ettinghausen: Muslim Decorative Arts

; op cit; p. 13.

[2]

R. Ettinghausen: The Character of Islamic Art; in The

Arab heritage (N.A. Faris ed); op cit; pp 251-67; at p.

256.

[3]

Ibid. p. 257.

|