Islamic Libraries

According to Yaqut, when Nuh Ben Mansur offered a governorship

to al-Sahib b. Abbad (938-995), the latter declined it. He

justified his decision on the ground that it would be difficult

to transport his books, estimated at 400 camel-loads. Obviously,

he much preferred the company of his books to the appointment.[1]

For Al-Hakam II (Caliph in

‘The

well being of my children, the children of my brother and of our

wives allowed me to accept the loss of my wealth with ease. What

distressed me was the loss of my books. These were four thousand

volumes, all precious works. Their loss was the cause of life

long sorrow for me.’[4]

A

passion for books in early Islam well expressed by the words of

al-Jahiz (776-868):

‘The

book is the companion with whom you do not get bored; it is the

friend who does not tire you; it is the colleague who does not

deprive you of what you possess through his flattery… If you

study the book, it will increase your store of knowledge,

sharpen your wit, add to your power of speech, increase your

vocabulary, broaden your mind, accord you the respect of people

and confidence of kings. Moreover you can learn from books in

only a month’s time what you cannot learn from people’s mouths

in ages…. As long as you associate yourself with them (books),

you do not need anybody else and you are not forced to prefer

loneliness over bad companionship; it relieves you of your

worries regarding scarcity of wealth and material prosperity and

absence of joy and merriment in your life. In fact, the one who

keeps company with books has been bestowed with great privilege

and highest favour.’[5]

A

Muslim scholar, of the 8th century, az-Zuhri,

possessed a huge collection of books, to which he devoted

himself, and so much so, his wife lamented, ‘I would prefer

three rival co-wives to his love for books.’[6]

Thus, just as it had a

passion for gardens, early Islamic society had a passion for

books, which contrasts sharply with the generalised contempt for

reading amongst most Muslims today, a passion for books

in early Islamic society that attracted the interest of many

historians of Islam such as Quatremere and Hammer Purgastall;[7]

a passion, whose basic inspiration was the faith, and which led

to two revolutionary changes: the public library, and book

production on a large scale.

The Islamic Library: Foundation, Rise and Scope

Islam the faith was, once more, central to the demand for books.

Reichmann notes how

God

created the pen as His great gift to humanity, and all past and

future actions of humans are noted in the heavenly books, (as

evidenced by the term maktub, (it is written).[8]

There are many quotations from the Qur’an in praise of writing,

for instance, ‘writing is the tongue of the hand.’ The word

Qur’an stems from qara’a: to read, or Qur’an ‘recitation’.[9]

The writing of Islamic books was a religious commitment, the

reading of the Qur’an was a sacred duty demanded from every

believer, and to know the entire Qur’an by heart was meritorious

and highly rewarded.[10]

This accounts for Islamic civilisation becoming a book culture.[11]

A culture of the book could only result in the

institutionalisation of book collection and distribution, hence,

the library.

The

origin of the Islamic library could go as far back as to the

early Umayyad rule (661-750), when Caliph Mu’awiya (661-80)

established at Damascus

in the early period of

his reign a library called Bayt al-Hikma

(House

of Wisdom), housed in a large building, and containing a

large collection of books.[12]

His successor, Khalid Ibn Yazid followed suit, and also

established a special library that accumulated a large number of

books, including his favourite subject, chemistry.[13]

Successive caliphs, whether East or West, did the same at

different times in the history of early Islam.

Abu Yaqub, the

Almohad ruler of

Libraries

were densely spread

throughout medieval Islamic society, from one end of the realm

to the other.[17]

‘I

remained there (in Merw) three years… Were it not for what

happened after the coming of the Tartars to that land and its

devastation… I surely would not have left it till death because

of the people’s generosity, kindness, and sociability, and the

multitude of sound fundamental books there. For when I left it

there were in it ten endowed libraries, the like of which, in

numbers of books, I had never seen. Among them were two

libraries in the mosque, one of them with 12,000 volumes… and

there is the library of Sharaf al-Mulk, the accountant; and the

library of Nizam al-Mulk in his mosque; and two libraries

(belonging to the Samani faculty), and another library in

the

And

so it was through the

One

of the most famed libraries of Islam was that of

Rulers and leading figures played a crucial part in the life of

the libraries. The university of Al-Mustansiriya of

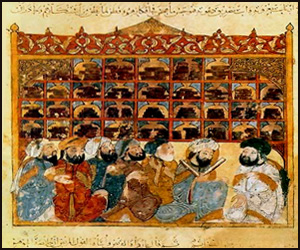

‘A complex of buildings surrounded by gardens with lakes and

waterways. The buildings were topped with domes, and comprised

an upper and a lower story with a total, according to the chief

official, of 360 rooms.... The library, which contained much

scientific literature was in the charge of a director, a

librarian and a superintendent. The books were stored in a long

arched hall, with stack rooms on all sides. Against the walls

stood book-presses, six feet high and three yards wide, made of

carved wood, with doors which closed from the top down, each

branch of knowledge having separate book cases and catalogues.

In each department, catalogues were placed on a shelf... the

rooms were furnished with carpets...'[50]

A considerable number of private libraries thrived, too,

especially amongst scholars. Amongst

the scholars of Islam,

there was none who could be found without a collection of books

of his own, Shalaby, thus, concluding, that the number of these

libraries equalled the number of learned people.[51]

This collection was an indispensable tool for the scholar, and

it included, in general, all the works that his never

interrupted studies allowed him to buy or copy.[52]

There are countless instances of such libraries.

Al-Waqidi, at his death, in the year 823, left 600 boxes of

books, each so heavy that two men were needed to carry it[53]

Al-Baiqani (1033) had so many books that it required sixty three

hampers and two trunks to transport them, whilst a 10th

century scholar, Mohammed ben al-Husain of Haditha had a

collection of rare manuscripts that was so precious that it was

kept under lock and key.[54]

The library of the

physician Ibn al-Mutran, had, according to Ibn Abi Usaybi'a more

than 3000 volumes; and three copyists worked constantly in his

service.[55]

And we hear of a private library in

Private

libraries were numberless amongst other groups, for it was a

fashion among the rich to have an ample collection of books.[60]

Among such libraries, the

library of Abu al-Mutrif (d. 1001), a Cordovan judge, was sold

at auction in the mosque for a whole year, bringing in 40,000

dinars.[61]

Al-Maqqari quotes this passage from Ibn Said who held:

‘To

such an extent did this rage for collection increase that a man

in power or holding a situation in the government considered

himself obliged to have a library of his own and would spare no

trouble or expense in collecting books merely in order that

people might say ‘such a one has a very fine library.’[62]

Muslim scholars’ bequests of books, and the establishment of

waqfs for the purpose, served to enrich the libraries

considerably. Al-Khatib al-Baghdadi (d. 1070) constituted into a

waqf all his works and writings for the benefit of Muslims. Some

such works are known to us.[63]

The Faqih al-Humaydi (d. 1095), also known as man of letters,

loved books so much that he worked at night copying them.

He also constituted his collection into a waqf

for the benefit of those engaged in scientific work.[64]

This must have been a rich collection, for he copied much and

gathered plenty of notes. Al-Mustazhari (d. 1115), a very pious

and generous figure, also constituted as a waqf for the learners

of Tradition

, a good number of books, which included the masnad of

Ibn Hanbal.[65]

Al-Katib (d. 1218), the last representative of the family of

writers of Banu Hamdan, constituted as a waqf for the benefit of

students a good part of his collection, made up of many original

works.[66]

Ibn Harit (d. 1322), a Faqih, a reader and lexicographer

constituted his book collection as well as his properties into a

waqf.[67]

The chief of physicians, Al-Muhaddab Ibn Ali al-Dawhar (d. 1230)

made of his house south of the Umayyad Mosque

in

One of the most notable traditions long held by the Muslims was

to bequeath their manuscripts and book collections, sometimes

thousands of volumes, to mosques.[69]

As Pedersen notes, because mosques were not just devoted to

worship, but were also seats of learning, it was normal that

people should give their libraries to mosques, and an entire

book collection might be transferred to a mosque as a self

contained library or dar al-kutub.[70]

Al-Jaburi reported that Naila Khatun, a wealthy widow of Turkish

origin, founded a mosque

in memory of her deceased husband, Murad Afandi. She attached to

the mosque a madrasa and a library for which she reportedly

bought many valuable books and manuscripts.[71]

In Iraq

, the Abu Hanifa mosque had an impressive library, which

benefited from the gifts of private collections, amongst which

was one by the physician, Ibn Jazla (d 493H/1099) and the writer

historian al-Zamakhshari (d 538H/1143).[72]

In Aleppo

, the largest and probably the oldest mosque library, the

Sufiya, located at the city's Grand Umayyad Mosque

, contained a large book collection of which 10 000 volumes were

reportedly bequeathed by the city's most famous ruler, Prince

Sayf al-Dawla.[73]

The famed historian, Abu’l Fida, built in the city of

Muslim Libraries: Their Public Role and their Management

Mackensen notes

that the contrast between the Christian West and medieval Islam

was not just in terms of size of book collections, but also

extended to the fact that whilst Western Christendom restricted

access to books, Islam encouraged it.[81]

The Islamic attitude, again, derives from

the Prophet’s summons:

‘The first blessing that accrues to a person occupied with the

transmission of traditions consists of the fact that he has the

opportunity to lend books to others.’[82]

This summons permeated all echelons of Islamic scholarship and

society; the scholar abided by it, and elaborated on it.

Ibn

Jammah's advised his students in his Books as the Tools of

the Scholars, written in 1273:

‘Books are needed in all useful scholarly pursuits. A student,

therefore, must in every possible manner try to get hold of

them. He must try to buy, or hire, or borrow them, since these

are the ways to get hold of them. However, the acquisition,

collection, and possession of books in great numbers should not

become the student's only claim to scholarship.... Do not bother

with copying books that you can buy. It is more important to

spend your time studying books than copying them. And do not be

content with borrowing books that you can buy or hire.... The

lending of books to others is commendable, if no harm to either

borrower or lender is involved. Some people disapprove of

borrowing books, but the other attitude is the more correct and

preferable one, since lending something to someone else is in

itself a meritorious action and, in the case of books, in

addition serves to promote knowledge.’[83]

Many libraries were founded for the sole purpose of lending

books.[84]

We even find in the waqf stipulations the basic rule for book

lending. Thus, in luga 42 of the Zahiriya Library, the

following rule stipulated by the waqf said:

‘Gifted for the profit of all Muslims and deposited at the

madrasa al-Gawziyya of

In Islam, in fact, caliphs, viziers, and scholars, were

extremely generous in supporting access to, and use of

libraries, including their own. In the Grand Palace of Ali b.

Yahya al-Munajjim (897) in

The organisation and management of Muslim libraries was quite

remarkable, and descriptions

of both public and private libraries speak of the classification

of books and their arrangement in separate cases or even in

separate rooms in the

There was accurate cataloguing of all contents to help readers,

whether the library was private or public. One single private

collection required 10 volumes,[101]

whilst in

It was the practice to appoint a librarian to take charge of the

affairs of the library,[105]

but such duty was only for the most learned amongst Muslims;

only men ‘of unusual attainment’ were allowed the privilege to

be custodians of the libraries.[106]

The Sufiya of the Grand Mosque

of Aleppo

library, for instance,

had in charge of it Muhammad al-Qasarani, an accomplished poet

and a man well versed in literature, geometry, arithmetic and

astronomy.[107]

The Nizamiya library of

Equally intensely sought after were copyists and it was the

generalised rule in Muslim libraries to employ many of them

together with calligraphists, and to employ the most illustrious

of them.[112]

Caliph al-Hakam II of

Generally,

From the point of view of their role in Muslim society and their

place in human civilisation, their organisation and functions,

their size and impact, and their innovative character,

Islamic public

libraries, Eche concludes, did not just surpass by far any

similar institution that might have existed elsewhere, but they

were only surpassed by modern libraries by around the 17th

century after mass printing made possible the distribution of

books on a grand scale.[125]

Most certainly, Islamic private libraries could be ranked on the

same level of importance.

The Rise of the Book

Industry

The

early Muslim passion for books did not just lead to the rise of

one of the greatest institutions of human civilisation, it also

led to the advent and advancement of some essential functions,

crafts and trades, which had dramatic effects on the worlds of

intellect and industry.

Muslims were great book collectors, and this stimulated a

flourishing book trade.[126]

At its foundation was the Warraq profession

(waraq being the Arabic

word for paper), which developed considerably.[127]

The Warraqeen (plural Warraq) traded mostly in paper, but

also copied rare manuscripts they managed to obtain from often

distant places, and made them available to the public at

reasonable prices.[128]

The manuscripts that the warraqs transcribed during

public dictations had little value unless they carried the

ijaza (licence), they were copies authorized by their

authors.[129]

The function of getting the ijaza and distributing the

approved manuscripts was performed by the warraqs, a process,

which was long and complicated, but which ensured that the

rights of the author were preserved and plagiarism was kept at

bay.[130]

Once the warraq made a copy of the author's work, it was read

back to him three or more times in public; each time, the author

making amendments or additions which required further readings.[131]

Only when the author was finally satisfied, did he place the

ijaza on the copies that he approved; the ijaza signifying that

he granted permission 'to transmit the work from him' in the

form as approved. If the author of a particular work was dead,

then the copy was read out by a distinguished scholar, who

charged an honorarium for his service and gave his ijaza to the

manuscript.[132]

The ijaza did not give the warraq copyright over the work; it

was simply an assurance that he passed the book in the form

determined by the author and was empowered to transmit the book

in the same form to others.

[133]

The profession of warraq also stimulated a diversity of trades,

here well outlined by

Durant. The Warraqs, he said:

‘Made ever lovelier Kurans for Seljuk, Ayyubid, or Mamluk

mosques, monasteries, dignitaries, and schools, and engraved

upon the leather or lacquer bindings designs as delicate as a

spider's web. Rich men spent small fortunes in engaging artists

to make the most beautiful books ever known. A corps of

papermakers, calligraphers, painters, and bookbinders in some

cases worked for seventeen years on one volume. Paper had to be

of the best; brushes were put together, we are told, from the

white neck hair of kittens not more than two years old; blue ink

was sometimes made from powdered lapis lazuli, and could be

worth its weight in gold; and liquid gold was not thought too

precious for some lines or letters of design or text.’[142]

Paper, a Chinese invention, was turned by the Muslims into an

industry that led to the massive production of books. The

literary necessities of a highly educated population, the

multiplication of manuscripts, the requirements of innumerable

institutions of learning, and the need to stack the shelves of

libraries, in turn stimulated the industry.[143]

The

use of paper rather than papyrus or parchment, in turn, made

books relatively cheap.[144]

Thus, whilst elsewhere

books were ‘published' only through the tedious labour of

copyists, in the Muslim world hundreds, even thousands of copies

of reference materials were made available to those wishing to

learn.[145]

All this had decisive impacts subsequently, when transmitted to

the West. The Europeans of

the Middle Ages wrote only on parchment but its high price was a

serious obstacle to the multiplication of written works.[146]

By making use of this new material, paper, and manufacturing it

on a large scale, in the words of Pedersen, the Muslims

‘accomplished a feat of crucial significance not only to the

history of the Islamic book but also to the whole world of

books.’[147]

[1]

Yaqut, ibn-' Abd Allah al-Hamawi,

Irshad al-Arib

ila Ma'rifat al-Adib, also referred to as

Mu'jam al-Udaba,

(Dictionary of Learned Men,) edit., D.S. Margoliouth

(Luzac, 1907 ff); vol II, p. 315.

[2]

R. Mackensen: Moslem Libraries

and Sectarian

propaganda, in The American Journal of Semitic

Languages (1934-5), pp 83-113 at p. 108.

[3]

S.K. Bukhsh: Studies; 49-50; in W. Durant: The Age;

op cit; p. 236.

[4]

M. Erbstosser: The Crusades; op cit; p. 136.

[5]

Al-Jahiz: Kitab al-Hayawan (the Book of Animals)

ed. F. Atawi; vol1; pp. 33-5. in A.L.A. Ibn Dohaish:

Growth and Development of Islamic Libraries

; in Der Islam, vol 66; pp.289-302. at p. 299.

[6]

Ibn Khallikan: Wafayat al-Ayan; vol iii; p. 317,

in A.L.A. Ibn Dohaish: Growth and Development; p. 292.

[7]

M. Quatremere: Memoires sur le gout des livres chez les

Orientaux; in Journal Asiatique; VI; (1830); pp.

35-78.

-H. Purgastall: Additions au memoire de M. Quatremere

sur le gout des livres chez les Orientaux; Journal

Asiatique; XI (1848), pp. 178-98.

[8]

F. Reichmann: The Sources of Western Literacy

(Greenwood Press; London; 1980), p.205.

[9]

Ibid.

[10]

Ibid.

[11]

A. Grohmann: Arabische Palaeographie;

[12]

Y. Eche: Les Bibliotheques Arabes; Institut

Francais de Damas (Damascus

; 1967), p. 11.

[13]

A.L.A. Ibn Dohaish: Growth and Development; op cit; p.

295.

[14]

G. Deverdun: Marrakech

; Editions Techniques Nord Africaines (Rabat; 1959),

p.265.

[15]

Ibid.

[16]

Ibid.

[17]

O. Pinto: ‘The

Libraries

of the Arabs

during the time of the Abbasids

,' in Islamic Culture 3 (1929), pp. 211-43.

[18]

S.K. Padover: Muslim Libraries

; in The Medieval Library; edited by J.W.

Thompson (Hafner Publishing Company; New York; 1957 ed),

pp. 347-68;

at p. 352.

[19]

A. Von Kremer: Culturgeschichte des Orients under den

Chalifen (

[20]

See G. D’Ohsson: Histoire des Mongols; op cit;

vol 3.

[21]

S.K. Padover: Muslim Libraries

; op cit;

pp. 351-2.

[22]

R. Landau:

[23]

F. Reichmann: The Sources of Western Literacy; op

cit; p.208.

[24]

G. Le

Bon: La Civilisation; op cit; p. 343.

[25]

Yaqut: Mu’jam in J. Pedersen: The Arabic Book, p.

128.

[26]

See final part under appropriate heading for the fate of

Muslim libraries.

[27]

W. Durant: The Age of Faith; op cit; p. 329.

[28]

Yaqut, Ibn Abd Allah al-Hamawi:

Jacut's Geographisches Worterbuch,

ed. F. Wustenfeld. 6 vols (Leipzig, 1866-70), vol iv; p.

509;

[29]

A. Shalaby:

History of Muslim Education

(Dar Al Kashaf;

Beirut; 1954), p

95.

[30]

Y. Eche: Les Bibliotheques; op cit; p. 299.

[31]

M. Quatremere: Memoires sur le gout des livres chez les

Orientaux; op cit.

[32]

R. Rohricht: Geschichte des konigreichs

[33]

M. Michaud: Histoire des Croisades (Paris; 1825),

II; p. 54.

[34]

Kurd Ali: Khitat al-Sham;

[35]

Al-Dahabi: Tarikh al-Islam; Aya Sofya; 4009; vol

XI; year 499 H.

[36]

Y. Eche: Les Bibliotheques Arabes; op cit; p.

118.

[37]

Al-Nuwayri BN, ar. 1578; 116 r. in Y. Eche: Les

Bibliotheques Arabes; op cit; p. 118.

[38]

Y. Eche: Les Bibliotheques Arabes; op cit; p.

118.

[39]

Ibn Al-Furat: Tarikh al-Duwal wa’l Muluk; Ms

National Library of Vienna; A.F. 117; I; p. 38.

[40]

Y. Eche: Les Bibliotheques Arabes; op cit; p.

119.

[41]

Sibt al-Jawzi in Recueil des Historiens Orientaux des

Croisades (Paris; 1884), III; 536.

[42]

Ibid; p.102.

[43]

Ibid.

[44]

Al-Makrizi: al-Khitat, op cit, II, p. 366.

[45]

J. Pedersen: The Arabic Book, op cit, p. 120.

[46]

Al-Maqqari: Nafh al-Tib, op cit II, p 180.

[47]

J. Pedersen: The Arabic Book; op cit; p.120:

[48]

G Le Bon: La Civilisation; op cit; p. 343.

[49]

J. Pedersen: The Arabic Book; op cit; p 121.

[50]

AL-Muqqadasi: Ahsan al-Taqasim; edited by de

Goeje, op cit; p. 449; Von Kremer:

Culturgeschichte

des Orients under den Chalifen;

op cit; II; pp. 483-4.

[51]

A. Shalaby: History, op cit, p. 107.

[52]

Y. Eche: Les Bibliotheques; op cit; p. 282.

[53]

E.G. Browne: Literary History of

[54]

S.K. Padover: Muslim Libraries

; op cit; pp. 351-2.

[55]

In F. Micheau: The Scientific Institutions in the

Medieval Near East, in The Encyclopaedia of the

History of Arabic Science, Ed by R. Rashed

(Routledge; London; 1996), pp 985-1007, at p. 988:

[56]

F.B. Artz: The Mind; op cit; p.153.

[57]

G. Deverdun: Marrakech

; op cit; p. 265.

[58]

Ibid.

[59]

Y. Eche: Les Bibliotheques; op cit; p. 282.

[60]

W. Durant: The Age of Faith; op cit; p. 236.

[61]

W. Gottschalk: Die Bibliotheken der Araber im Zeitalter

der Abassiden;

Zentralblatt fur Bibliothekswesen; XLVII

(1930); pp. 1-6.

[62]

P. De Gayangos:

The History of the Mohammedan Dynasties in Spain

(extracted from

Nifh Al-Tib by al-Maqqari); 2 vols (The Oriental

Translation

Fund; London, 1840-3), Vol 1; pp. 139-40.

[63]

Y. Eche: Al-Habib al-Baghdadi (

[64]

Al-Dahabi: Tadkirat al-Hufaz; Hydarabad; ND; IV;

p. 20; Al-Maqqari: Nafh al-Tibb; I; p. 382.

[65]

Muntazam; ed. Haydarabad; IX; p. 183. in Y. Eche: Les

Bibliotheques; op cit; p. 196.

[66]

Al-Dubayti: Dayl Tarikh al-Salam; Mss at the

Bibliotheque Nationale (

[67]

Al-Safadi: Al-Wafi bi’l wafayat; Ms of Ahmad III;

Istanbul; No 2920; ed. Ritter; I; p. 232.

[68]

Sibt al-Jawzi: Mir’at al-Zaman; Ms of Bibliothque

Nationale; ar. 1505; 1506; 5866; ed by J. Richard (

[69]

R. Mackensen: Background of the History of Muslim

libraries.' The American Journal of Semitic Languages

and Literatures, vol 51; Four Great Libraries

....', op cit.

[70]

J. Pedersen: The Arabic Book, op cit, p. 126.

[71]

Al-Jaburi, Maktabat al-Awqaf... op cit. p, 89, in M.

Sibai: Mosque

Libraries

, op cit, p 92.

[72]

M. Sibai: Mosque

Libraries

, op cit, p 81.

[73]

Ibid; p 71.

[74]

M. Kurd Ali: Khitat al-Sham. 6 Vols, (Damascus

: Al-Matbaa al Haditha, 1925-8), IV; p. 193.

Y. Eche: Les Bibliotheques; op cit; p. 248.

[75]

Ibn Higga: Tamarat al-awraq (Cairo

; 1339), I; p. 75.

[76]

Ibn al-Imad: Shaderat al-dahab, v: 122, in A.

Shalaby: History, op cit, p. 101.

[77]

M al-Rammah: The Ancient Library of Kairaouan and its

methods of conservation, in The Conservation

and preservation of Islamic manuscripts,

Proceedings of the Third Conference of Al-Furqan Islamic

Heritage Foundation (1995), pp 29-47, p. 32.

[78]

A al-Fasi: ‘Khizanat al Qarawiyyin wa nawadiruha,'

Majallat Mahad al-Makhtutat al-Arabiya 5 (May 1959):

3-16. p. 9.

[79]

W. Heffening: Maktaba; in Encyclopaedia of Islam,

op cit; vol VI, p. 199.

[80]

M. Sibai: Mosque

Libraries

, op cit, p 90.

[81]

R. Mackensen: Moslem Libraries

; op cit; p. 109.

[82]

In M. Sibai:

Mosque

Libraries

,

op cit; p.

105.

[83]

In F. Rosenthal: Technique and Approach of Muslim

Scholarship (Rome; Pontificum Institutum Biblicum;

1947), pp. 8-9.

[84]

Y. Eche: Les Bibliotheques Arabes; op cit; p.

384.

[85]

Ibid.

[86]

Yaqut: Muujam al-Udaba, op cit; V, p. 467.

[87]

O. Pinto: Le Biblioteche degli Arabi nell eta degli

Abbasidi; in Bibliofilia di L. Olschki; vol XXX;

p.151.

[88]

Y. Eche: Les Bibliotheques Arabes; op cit; p. 99.

[89]

R.S. Mackensen: Background; op cit.

[90]

W. Durant: The Age of Faith; op cit; p. 237.

[91]

Yaqut al-Hamawi quoted in A.L.A. Ibn Dohaish: Growth and

Development; op cit; p. 297.

[92]

Yaqut: Mu’jam; op cit; II, p. 420.

[93]

S.K. Padover: Muslim Libraries

; op cit;

p. 353.

[94]

A. Mez: Die Renaissance des Islams (Heidelberg;

1922), p. 95.

[95]

A Shalaby:

History; op cit; p. 98.

[96]

S. Khuda Bukhsh: The Renaissance of Islam; Islamic

Culture; IV (1930), p. 297.

[97]

Ibid; p. 295.

[98]

M. Sibai: Mosque

Libraries

,

op cit; p 55.

[99]

F.B. Artz: The Mind; op cit; pp.152-3.

[100]

O. Pinto: The Libraries

; op cit; p. 227.

[101]

F.B. Artz: The Mind; op cit; p.153.

[102]

Al Maqqari: Nafh

al-Tib, op cit; I, p. 186.

[103]

O. Pinto: The Libraries

; op cit; p. 229.

[104]

A. Shalaby: History; op cit, Pp 82-3.

[105]

E.L. Provencal: Nukhab Tarikhiya Jamia li Akhbar

al-Maghrib

al-Aqsa

(Paris: La Rose, 1948), pp 67-68.

[106]

R.S. Mackensen: Background, op cit; p. 24.

[107]

Y. Eche: Les Bibliotheques Arabes,

op cit p. 134.

[108]

Asnawi: Tabakat al-Safi’ya; ms of the Zahiriya;

Tarikh; 56; 18 v. and 19 r.; Al-Subki: Tabaqat

al-Safi’ya (

[109]

Yaqut: Irsad al-Arib; ed. Margoliouth; vol vii;

p.286.

[110]

S.P. Scott: History; op cit; vol 3; p.465.

[111]

R.S. Mackensen: Background; op cit; p. 24.

[112]

Y. Eche: Les Bibliotheques; op cit; p. 273.

[113]

Ibn Khaldun

: Al-Ibar wa diwan al-mubtada wa’l-habar; ed

Bullaq (1284 (H); IV; p. 146.

[114]

Ibn al-Abbar: Kitab al-Takmila (

[115]

Al-Safadi: Al-Wafi bi’l wafayat; Ms of Ahmad III;

Istanbul; No 2920; XIX; p. 118 v;..

[116]

S.K. Padover: Muslim libraries; op cit; p. 362.

[117]

Ibid.

[118]

Ibid.

[119]

S. Watts: Disease and Medicine in World History

(Routledge; 2003), p.40.

[120]

Ibid.

[121]

S. Watts: Disease and Medicine;

op cit; p.40.

[122]

Y. Eche: Les Bibliotheques; op cit; p. 274.

[123]

Ibid; p. 275.

[124]

Ibid.

[125]

Ibid; pp. 396-7.

[126]

F.B. Artz: The Mind; op cit; p.152.

[127]

M. Sibai: Mosque

Libraries

, op cit, p. 41.

[128]

Ibid.

[129]

Z. Sardar-M.W. Davies: Distorted Imagination; op

cit; p. 99.

[130]

Ibid.

[131]

Ibid.

[132]

Ibid.

[133]

Ibid.

[134]

W. Durant: The Age of Faith; op cit; p.319.

[135]

Ibid; p. 236.

[136]

G. Wiet et al: History; op cit; p.448:

[137]

Yaqut: Mu'jam

al-Udaba; op cit; Vol VI, p. 56.

[138]

S.K. Padover: Muslim Libraries

; op cit; p. 361.

[139]

Ibn Zulaq, Akhbar Sibawiy al-Misri, pp. 33, 44 MS

1461;

[140]

Al-Makrizi: al-Khitat, vol I, p. 361, Vol II p.

96.

[141]

Sayid Amir 'Ali: in A. Shalaby: History, op cit,

p. 28.

[142]

W. Durant: The Age of Faith; op cit; p.319:

[143]

S.P. Scott: History; op cit;

vol 2; p. 387. J. Pedersen: The Arabic Book;

op cit; pp. 50 sq.

[144]

F.B. Artz: The Mind; op cit; p.152.

[145]

M. Nakosteen: History, op cit, p. 37.

[146]

G Le Bon: La Civilisation; op cit; p. 391.

[147]

J. Pedersen: The Arabic Book, op cit, p. 59. |