|

Institutional/Organisational Impact

Translations were

essential, but were not alone to lead to both beginning and

operations, or functioning of institutions of higher learning in

the West. A variety of other factors, also derived from Islam,

contributed to such developments. These influences have been

studied by Ribera[1]and

his followers, but refuted by Rashdall and his.[2]

Before looking at

the Islamic influences, it is first necessary to look at, and

refute, Rashdall and his followers’ argument, which insists that

Western universities were first on the scene, and as such owe

nothing to any Islamic influence.

Rashdall and his

followers’ main point is that Western universities were the

first true universities because they were set up by royal

prerogative.[3]This

is historically false. Contrary to what Rashdall and his

followers[4]

hold, no Western university, with the exception of Naples (set

up by Frederick II

in 1224) was established

by prerogative, or as a distinct institution. Haskins

,

indeed, notes, that at least five universities go back to the 12th

century: Salerno

,

Bologna, Paris, Montpellier

and Oxford.

`Nevertheless,’ he points out,

`these have not entirely emerged from the general group

of schools: the name university is scarcely known in this sense;

its distinctive organisation is scarcely recognised;

universities do not yet associate exclusively with other

universities, nor has the Papacy laid its guilding hand upon

them.’[5]There

are, for instance, no statutes for the Parisian medical

faculty before 1270.[6]

Similarly, Sarton

notes, the eighth

hundredth anniversary of the university of Bologna having been

celebrated with considerable pomp in 1888, led many people to

conclude that it must have been founded in 1088. But this is

purely arbitrary Sarton adds, as it is impossible to say when

the university was founded, for there never was a charter of

foundation for it.[7]

It was only by the middle of the 12th century that

its school of law was famous, and the university was only

completely organised towards the end of that century (12th).[8]

Likewise, Clagett explains that the use of the term "university"

(Latin

,

universitas) is somewhat misleading.[9]During

the 13thcentury it designated "an association or

guild of either masters or students or both," but it was not

limited to educational groups or learning associations, but was

used for other associations or guilds. Thus a university did nor

mean, as it does today, a group of faculties or schools.[10]

Something more in line with our use of the word today, Clagett

pursues, was the Latin term `studium generale,’ but even this

expression is also misleading, since `generale’ does not refer

so much to different faculties as to the fact that the studium

was open to all comers. The studium referred to the institution,

its place and courses, but not to the organization of its

personnel.[11]

And, again, back to Haskins, who insists, that despite

indications of considerable bodies of masters and students and

of vigorous intellectual life, there is very little evidence of

formal university organisation.[12]

It is, equally found vain by Sarton to try and fix the exact

dates of the foundation of these universities, for the simple

reason that, indeed, they were not deliberately founded.[13]

Various acts of incorporation were given to them later,

sometimes much later, when they had grown to a respectable size

and shown by their own being what a university was. And the fact

that not merely one university grew in that manner-somewhat

unconsciously, like a living thing-but many, in different

countries, proves, Sarton concludes, `that these creations

answered a definite need of the time.’[14]

And that need, he explains, was due to the vast influx of

knowledge in the 12th century, so large learning,

`that systematic methods of education became necessary. In the

meantime the growth of cities had made the application of such

methods at once more tempting and more easy. Thus our

universities appeared in the second half of the 12th

century, and not before, because there had not been sufficient

scope nor opportunity for them until that time, and they

appeared then because the need was suddenly urgent.’[15]

From

the preceding two conclusions can be derived:

First, contrary to what Rashdall and his followers hold, all

Western institutions of higher learning operated for decades, at

least, before they were officially set up.

Second, it was the influx of Islamic learning that was at the

foundation of the origin, and very existence of such

institutions.

And whilst both these

two points have been amply proved, Rashdall and his followers

cannot provide a single piece of evidence to show one single

document establishing such institutions officially at the very

start of their existence. They can neither provide one single

piece of evidence showing these universities providing any

advanced teaching prior to the translations from Islam, or

lecturing anything advanced other than what was translated from

Arabic, except in theological sciences.

To

reinforce the points just made, the first university to be

founded at a definite time, by a definite charter in Western

Christendom

was the University of

Naples, founded in 1224 by Frederick II

.[16]

Its other distinction: it was the first university in the

Western world that relied primarily on Islamic learning and

Islamic model of teaching. Lest the learning of the scholars

whom he had assembled should die with their deaths, Durant

holds,[17]Frederick

founded it in 1224, a rare example of a medieval university

established without ecclesiastical sanction.[18]

Frederick’s deep knowledge of the Muslim world, allowed him,

according to Mieli

, to

know and appreciate the Muslim precedents, which explains his

founding of Naples University.[19]

More importantly, Frederick called to its faculty scholars in

all arts and sciences, and paid them high salaries; and he

assigned subsidies to enable poor but qualified students to

attend.[20]

Frederick also established universities in Messina and Padua,

and renovated the old medical school of Salerno

`in accordance with the

advances of Arab medicine.'[21]

Naples was, thus, unique, and Rashdall and his followers, hence,

are telling a major fallacy when they attribute what is proper

and unique to Naples to other Western Christian universities,

when neither Rashdall nor his followers can show an earlier

single piece of evidence of official founding at a precise date

for any such universities. And Naples was unique because it was

the most directly inspired institution from Islamic models,

founded by an Islamic inspired ruler, its teaching based on

Islamic science

,

and its principal function being to disseminate Islamic

learning.

To

demonstrate further both the Islamic pioneering role in higher

learning, and the Islamic impact on the Christian West

, it

is important to address the issue from two distinct angles:

-First to show that institutions of higher learning were

established in Islam centuries before their counterparts in the

Christian West

.

-Second, to show in detail some models of borrowing in the

organisation of the first Western universities from their

Islamic counterparts.

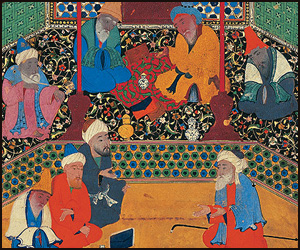

On

the first point (the pioneering aspect), in Islam, there was

some organisation of higher education as early as the beginning

of the 9th century, Watt notes, and by the end of the

11th century, university-type institutions had been

established in most of the chief cities.[22]

Earliest of all, is Bayt al-Hikma (the house of Wisdom), founded

in the 9th century by Caliph Al-Mamun, and which has

in all manners and forms the making of the earliest modern

institution of advanced learning, including scientific

equipment, a translation bureau, and an observatory. Instruction

included rhetoric, logic, metaphysics and theology, algebra,

geometry, trigonometry, physics, biology, medicine, and surgery.[23]

The institution was set up by the Caliph, himself, officially,

and was funded by the central authority. In such an academy

worked or collaborated the most eminent court scholars of the

time: The Banu Musa

Brothers

(mathematicians, and astronomers,) Al-Khwarizmi

;

al-Battani, and so on and so forth.[24]

In the same institution were recorded some of the earliest

Islamic achievements. In astronomy, for instance, there was

determined the position of the solar apogee,[25]the

inclination of the ecliptic,[26]was

calculated the earth circumference,[27]and

were made observations of

solar and lunar eclipses and planetary positions.

Then, of course, are the

university mosques; Watt pointed out (in 1972) that teaching has

been going on continuously for a thousand of years in the

university-mosque of Al-Azhar in Cairo

.[28]

And also at Al-Qarawiyyin (Fes), which dates from the middle of

the 10th century;[29]and

at Al-Qayrawan

even earlier, as some of

the medical texts mentioned above (that were translated by

Constantine the African

)

date from the 9th century.[30]The

curriculum in such places, Nakosteen points out, reminds us in

its extensive and intensive nature of curricular programs of

modern advanced systems of education, particularly on higher

levels of education.[31]

It was not unusual to find instruction in algebra, trigonometry,

geometry, chemistry, physics, astronomy, medicine, pharmacy,

history, geography etc.[32]

Some of the professors of polite literature, Draper notes, gave

lectures on Arabic classical works; others taught rhetoric or

composition, or mathematics, or astronomy.[33]

Specific instances show that astronomy and engineering were

studied at Al-Azhar,[34]

medicine also at Al-Azhar and the mosque of Ibn Tulun in Egypt

(9th

century).[35]

At the Qarrawiyyin, were dispensed courses on grammar, rhetoric,

logic, elements of mathematics and astronomy,[36]

and possibly history, geography and elements of chemistry.[37]

At Al-Qayrawan and Zaytuna in Tunisia

,

alongside the Quran and jurisprudence were taught grammar,

mathematics, astronomy and medicine.[38]And

these were no subjects of later centuries, quite the opposite.

At Al-Qayrawan, in particular, classes in medicine were

delivered by Ziad Ben Khalfun, Ishak Ben Imran and Ishak Ben

Sulayman (all scholars of the 9th century),[39]whose

works were subsequently translated by Constantine The African in

the 11th century at Salerno

.

And

whilst in the Christian West

,

the name, university, Haskins

notes, eludes search

before the 13th century, when it appears incidentally

in 1208-09 in the letters of a former student (Pope Innocent

III), where, as often in the history of institutions, the name

follows after the thing itself,[40]this

is not the case in Islam. The word `Jamia’ (university in

Arabic) appeared extremely early, and was linked with the first

mosque universities of Islam such as Al-Qarrawiyyin in Fes,

Al-Azhar in Cairo

,

Al-Qayrawan mosque, etc.[41]Jamia

derives precisely from Jamaa (mosque), the two institutions,

thus, having intricate links in curriculum and in name.[42]

And

the same mosque/university linkage observed with respect to

student organisation. The number of students at al-Azhar always

included hundreds of foreign students, many from far distant

lands; students who did not have homes in Cairo

were assigned to a

residential unit, which was endowed to care for them.[43]

Generally, the unit gave the resident students free bread, which

supplemented food given to them by their families, whilst better

off students could afford to live in lodgings near the mosque.

Every large unit also included a library, kitchen and lavatory,

and some space for furniture.[44]At

the Qarrawiyyin (Fes), students were given monetary allowances

periodically.[45]There,

students lived in residential quadrangles, which contained two

and three story buildings of varying sizes, accommodating

between sixty and a hundred and fifty students, all also

receiving a minimal assistance for food and accommodation.[46]

With

regard to the second point, the Islamic impact in relation to

organisation, is visible in all form, structure and also methods

of teaching and examination, which are seen in turn.

Ribera insists that in their structure and organisation, Western

universities were based on the Nizamiyah madrasa (college)

founded by the Seljuk minister in 1065 in Baghdad

.[47]

The students often lived in boarding houses (khan) under

supervision of their teacher and employed an inkwell as a

symbol.[48]A

chapel and a library, as well as residential arrangements for

students and teachers were a distinct feature of the madrasas,

the precursors of the residential colleges of British

universities.[49]

The Studia of medieval Europe, according to Hossein, were just

imitations of madrasas both in their name and free growth, and

that `the great Muslim madrassah was also the archetype of the

Studium General which, with the later requisite of the royal or

papal authorization, came to be known as university in Europe.'[50]

In going back to the origins, Makdisi points out, as it first

appeared in Paris, Oxford and elsewhere, the college was a

previous product of Islam; and that, in Merton College in

Oxford, `we have a watershed in the history of the college.’[51]

Merton stands as a dividing point between the college of Islam

on the one hand, and that of the United States on the other.[52]

Both

Islamic pioneering role and impact are also found in the manner

of teaching. At the madrasas, centuries before Abelard, the

dialectical method (jadal) was employed in disputations

(munazara).[53]

The different opinions were enumerated (khilaf), a consensus

(ijma) was sought in order to harmonise reason with faith. In

teaching, the dictation method was used, as teaching was

synonymous with dictation (imla).[54]

Classes were directed by a mudarris, who can be compared to a

professor, with `naib' (substitute professor,) and also a muid

who acts as a `drill master,' the latter repeating the teachings

of the professor like a `repetiteur' of Western universities.

From these institutions many of the practices observed in

Western colleges were derived, says Draper.[55]

They held commencements, at which poems were read and orations

delivered in presence of the public.[56]

Whilst going through the Azhar mosque during professorial

lectures, Le Bon notes, `it seemed a magic stick had taken me

back to our old 13th century universities. The same

confusion in the theology and literary studies, same methods,

same organisation of students gathered in corporations, and

benefiting of the same immunities and franchises.’[57]

Thus,

Gerard of Cremona

,

the first university lecturer, most probably in the first

Western university, Toledo

,[58]

was being heckled, but was not troubled, for we find him

conducting his collegium like a Muslim faqih (learned religious

person), anticipating counterarguments and sharpening his points

in a lively encounter with his students.[59]

In Paris, students sat on the floor, covered with straw, whilst

a professor lectured from a platform.

[60]

A

major step in the advance of higher learning was the

introduction of a system of examination and diplomas, and here,

again, was the primary role of the Islamic system and its

impact. It was under Roger II of Sicily

,

who was deeply influenced by Islamic antecedents and culture,

that was pioneered the foundation and establishment of medical

faculties and the granting of medical degrees. In 1140, he

enacted that everyone who desired to practice medicine must,

under pain of imprisonment and confiscation of goods, present

himself before a magistrate and obtain authorization.[61]Roger

introduced examination by experienced physicians of all

candidates for the profession of medicine and surgery,

restricting those whose learning was deficient to `the

clandestine ministrations of the shrine and the confessional.’[62]

Other rulers of Western Christendom followed his example, and

these measures ultimately led to the specialization of the study

of medicine and the granting of degrees by the medical faculties

of universities.[63]

The inception of the idea of the regularization of medical

practice by Roger of Sicily was probably related to his

`Arabist’ leanings, for the Arabs

had a system of

licensing in vogue in the centuries previously.[64]

It is necessary to remember that it was in 931, that Caliph

al-Muqtadir ordered that physicians had to have licence before

setting up practice.[65]

The beginnings of the

system of medical examinations, thus, are to be sought among the

`Arabs.’[66]Obtaining

a certificate was also the practice in even the earliest mosque

study, and as a rule, once a

student had been able to collect certificates from a number of

teachers, he was in position to seek employment in a mosque,

college, law court, government office or village school.[67]

Also

amongst others, Islam pioneered and influenced the West and the

course of university scholarship in the doctoral thesis and its

defence, and in the peer review of scholarly work based on the

concensus of peers.[68]

A characteristic of the teaching in Islamic schools of Spain was

that `dialectic tournaments' were customary among the students

and also among the teachers; this practice was introduced with

renewed vigour among the High scholastics of Medieval Europe,

through the Western Caliphate.[69]

The practice of these disputations was thus not entirely a new

idea to the Latin

West, and it is to this

custom that we owe the modern practice of demanding Theses and

Dissertations from aspirants to University Honours.[70]

And it is only in 1270 that we first find formal degrees

granted by Bologna.[71]After

having well studied his

trivium, the candidate for the Baccalaureat underwent an

examination, and had to enter into arguments upon grammar,

rhetoric, and dialectics.[72]

The title of doctor of medicine, first used by Giles of Corbeil

with reference to Salernitan graduates (when Salerno

was then under the rule

of Frederick) became the badge of honour of the most learned

physicians, and graduation ceremonies were made as impressive as

possible.[73]

More

on these matters can be found expanded upon by Makdisi.[74]

Bringing the two main sources, or traits, of Islamic influence

on the West (via learning, and models and organisation of

learning) is the 12th century Toledan experience.

Toledo

supplied the Christian

West

with learning more than

any other place did before in history through the translations

effected there. It

was also Gerard's (of Cremona) fame as a teacher and expounder

of Islamic science

that gave Toledo its

international stature and fame, says Metlitzki.[75]

Daniel (of Morley) found him lecturing to a body of students,

just like his Muslim predecessors, at the Toledo Mosque, which

shows that Toledo was the first de facto university in Christian

Spain, though it was not an official

studium generale.[76]

Daniel's eyewitness account of the proceedings is a unique

medieval document, Metlitzki observes; the effects of which,

even on the intellectual climate of medieval England

,

remain to be fully investigated.[77]And

when he left Toledo, Daniel, on his return to England did not

just take with him `a precious multitude of books,’ but, most

importantly, in order `to explain the teaching of Toledo to

Bishop John of Norwich (1175-1200),’[78]he

wrote his De philosophia.[79]

[1]

J. Ribera: Disertaciones y opusculos; 2 vols.

Madrid 1928.

[2]

H. Rashdall: The Universities

of Europe in the

Middle Ages, New edition by F.M Powicke and A.B. Emden,

3 Vols. Oxford University Press, 1936; pp 536-39

[3]

Ibid.

[4]

For instance: A.B. Cobban: The Medieval Universities

, their Organization and their Development;

Methuen; London; 1975.

[5]

C.H. Haskins

: The Renaissance

; op cit; p.65.

[6]

M McVaugh: Medical Knowledge at the time of Frederick II

, in Micrologus; Sciences at the Court of Frederick II;

op cit; pp 3-17; p.3.

[7]

G. Sarton

: Introduction; op cit; Vol II. p.351.

[8]

Ibid.

[9]

M. Clagett: The Growth; op cit; pp.79-80.

[10]

Ibid.

[11]

Ibid.

[12]

C.H. Haskins

: The Renaissance

; op cit; p.381.

[13]

G. Sarton

: Introduction, op cit; Vol II, p.285.

[14]

Ibid.

[15]

Ibid.

[16]

G. Sarton

: Introduction, vol 2; p. 575.

[17]

W. Durant: The Age of Faith; op cit; p. 720.

[18]

Ibid.

[19]

A. Mieli

: La Science Arabe; op cit; p. 228.

[20]

W. Durant: The Age of Faith; op cit; p. 720.

[21]

R.

Briffault: The Making, op cit, p. 213.

[22]

W. Montgomery Watt: The Influence; op cit; p. 12.

[23]

F.B. Artz: The

Mind, op cit; p. 151.

[24]

See: R. Briffault: The Making; op cit; pp. 187 fwd.

[25]

W. Hartner: The Role of Observations in Ancient and

Medieval Astronomy; in The Journal of History of

Astronomy

; Vol 8; 1977; pp 1-11; at p. 8.

[26]

J.L.E. Dreyer

: A History; op cit; p.246.

[27]

M. A. Kettani:

Science and Technology

in Islam: The

underlying value system, in

The Touch of

Midas; Science, Values, and Environment in Islam and the

West; Z. Sardar ed: Manchester University Press,

1984, pp 66-90.

p. 75.

[28]

W. Montgomery Watt: The Influence; op cit; p. 12.

[29]

R Landau, The Karaouine at Fes

The Muslim World

48 (April 1958): pp. 104-12.

M. Alwaye:

`Al-Azhar...in thousand years.' Majallatu'l Azhar:

(Al-Azhar Magazine, English Section 48 (July 1976): pp.

1-6.

[30]

See Entries on Al-Qayrawan, Encyclopaedia of Islam;

Brill; Leyden; first or second editions.

[31]

M. Nakosteen: History of Islamic; op cit;p.52.

[32]

Ibid.

[33]

J.W. Draper: A History; op cit; Vol II;

p.36.

[34]

M. Alwaye:

`Al-Azhar; op cit.

[35]

J. Pedersen:. `Some aspects of the history of the

madrassa' Islamic

Culture

3 (October 1929)

pp 525-37, p. 527.

[36]

R. Le Tourneau:

Fes in the Age of the Merinids, tr from French by

B.A. Clement, University of Oklahoma Press, 1961, p.

122.

[37]

Ibid.

[38]

H. Djait et al:

Histoire de la Tunisie (le Moyen Age); Societe

Tunisienne de Difusion, Tunis; p. 378.

[39]

Al-Bakri, Massalik, 24; Ibn Abi Usaybi'a, Uyun

al-anba, ed. and tr A. Nourredine and H. Jahier,

Algiers 1958, 2.9, in M. Talbi: Al-Qayrawan

; in Encyclopaedia of Islam, Vol IV, pp 829-30.

[40]

C.H. Haskins

: The Renaissance

; op cit; p.381.

[41]

See for instance:

B Dodge: Muslim Education in Medieval Times, The

Middle East

Institute,

Washington, D.C. 1962.

Rom Landau, The Karaouine at Fes, op cit.

A.H. Tazi: La

Mosque Al-Quaraouiyyine, 3 vols, edt Dar al-Kitab

Allubnani, Lebanon, 1973.

-R. Le Tourneau:

Fes avant le protectorat (Societe Maroccaine de

Librairie et d'Edition, Casablanca, 1947, pp. 453-471).

M. Alwaye: `Al-Azhar...in thousand years; op cit.

[42]

J. Waardenburg: Some institutional Aspects of Muslim

Higher Education and their relation to Islam. Nvmen:

International Review for the History of Religion 12

(April 1965) pp.96-138.

[43]

B. Dodge: Muslim Education, op cit, pp 26-7.

[44]

Ibid. pp 26-7, in particular.

[45]

J. Waardenburg: `Some institutional..' op cit,

p: 109.

[46]

B. Dodge, Muslim Education, op cit, p 27.

[47]

J. Ribera: Origen del Colegio Nidami de Baghdad

en Disetaciones

y opusculos, vol I; see A. Mieli

: La Science Arabe etc; op cit; p.145.

[48]

F. Reichmann: The Sources of Western Literacy;

Greenwood Press; London; 1980. p.207.

[49]

S.M Hossain: A Plea for a Modern Islamic University:

Resolution of the Dichotomy. in Aims and Objectives

of Islamic education: S.M. al-Naquib al-Attas edt;

Hodder and Stoughton; 1977. pp 91-103. P. 101.

[50]

Ibid. pp 101-2.

[51]

George Makdisi: On the origin and development of the

College in Islam and the West, in Islam and the

Medieval West; (Semaan ed): pp 26-49;

at. p.28.

[52]

Ibid.

[53]

F. Reichmann: The Sources. op cit;

p.207.

[54]

F. Reichmann: The Sources. op cit; p.207.

[55]

J.W. Draper: A History; op cit; Vol II; op cit; p.36.

[56]

Ibid.

[57]

G. Le Bon, La Civilisation des Arabes; op cit; p.336

[58]

D. Metlitzki: The

Matter of Araby;

op cit; p.37.

[59]

Ibid.

[60]

W.K. Ferguson: A Survey of European Civilisation,

London, George Allen and Unwin. p.277

[61]

D. Campbell: Arabian Medicine; op cit; p.119.

[62]

S.P. Scott: History; op cit;

vol 3; p. 26.

[63]

D. Campbell: Arabian mMdicine; p.119.

[64]

Ibid.

[65]

Abu al-Faraj Bar Hebraeus: Tarikh mukhtasar ad-Dual;

ed. Antun as-Salihani; Beirut, 1890; pp 281-2; in S.K

Hamarneh: Health and Sciences in Early Islam,

edited by M.A. Anees, Noor Health Foundation and Zahra

Publicaations; 1983, edt Vol 1, at p. 98.

[66]

T. Pushmann: History of Medical Education from the

most remote to the most recent times, trans and

edited by E.H. Hare (London, 1891); p. 181.

[67]

B. Dodge: Muslim Education; op cit; p. 25.

[68]

G. Makdisi: The Rise of humanism, op cit; p.350.

[69]

D. Campbell: Arabian medicine; op cit; p.58.

[70]

Ibid. p.59.

[71]

M McVaugh: Medical Knowledge at the time of Frederick II

, in Micrologus; op cit; pp 3-17:p.3.

[72]

P. Lacroix: Science and Literature; op cit; p.16.

[73]

G. Sarton

: Introduction, op cit; Vol II, p.96.

[74]

In G. Makdisi: The Rise of Humanism, op cit; especially

the last chapters.

[75]

D. Metlitzki: The

Matter of Araby;

op cit; p.37.

[76]

Ibid.

[77]

Ibid.

[78]

C.H. Haskins

: The Reception of Arabic science

in England

; English Historical Review; Vol xxx; London;

1915; pp. 56-69. pp. 67-8.

[79]

J.K. Wright: The Geographical Lore; op cit; p. 97. |