Optics

|

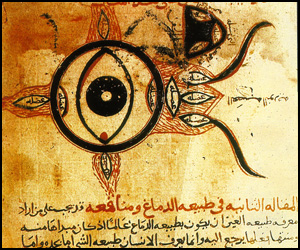

Ibn

al-Haytham (965-1039) is generally thought to be the only

Islamic contributor to optics with his Kitab al-manazir

(Book on Optics). In the more erudite works on the

subject, such as by Lindberg, one finds other Muslim scientists

involved in the subject.[1]

Rashed, too, has

made extensive studies with respect to some authors such as

al-Farisi.[2]

Djebbar makes a brief list of other authors and their works:

-Al-Kindi (801-873): Risala fi ikhtilaf al-manazir

(Treatise on Divergences in Optics).

Risala fi islah kitab Uqlidis

(Book on the Corrections of the Optics of Euclid.

-Ibn

Isa (10th c): Kitab fi l-hala wa qaws quzah

(Book on the Halo and the Rainbow).

-Ibn

Mansur (10th c): Kitab al-Manazir (Book on

Optics)

-Al-Farisi (13th c): Tanqih al-manazir

(Revision of the Book of Optics).

-Ibn

Ma’ruf (16th ): Kitab nur hadaqat al-absar

(Book on the Light of Accuity…)[3]

The

following outline is unable to go into these works and will

focus instead on pre-Islamic optics and on Ibn al-Haytham.

Pre-Islamic

(Greek) Theories of Vision

Optics remained for about thirteen centuries the battlefield of

the Greeks and their followers, the symbol of cogitation and

speculation triumphant over experimentation. The Greeks were

roughly divided into two diametrically opposed camps around the

issue of vision; those who stood by the ‘intromission' theory,

something entering the eyes representative of the object, and

those who stood by ‘emission,' vision occurring when rays

emanate from the eyes and are intercepted by visual objects.[4]

Within each half of the argument, there were more divisions.

Omar

explains that among

intromission theorists, opinion varied considerably, for example

around the manner in which the image is transmitted to the eye,

the nature of the medium, and so on.[5]

The difficulty in coming to a cohesive, precise

conclusion on optics resided with the multiplicity of the

arguments, and the fact that proponents of different arguments

were inconsistent on many accounts.[6]

Without getting bogged down in the complexities of the Greek

arguments, here is a brief outline of the issue of vision as it

stood before the Muslims.[7]

Basically, as Omar

explains, there were two

diametrically opposed Greek theories of vision. The first, the

intromission theory (Aristotle, Galen and followers), explained

vision in terms of the entry into the eye of ‘something'

representative of the object. Opposed to this was the emission

theory (Euclid and Ptolemy and followers,) which held that

vision occurs when rays emanate from the eye and are intercepted

by visual objects.[8]

Almost without exception, the Greek intromission theorists were

physicists, and so adopted a physical approach to the problem of

vision. Before Aristotle, Greek Atomists sought to apply

philosophical views, explaining vision in terms of ‘a coherent

form, a thin film of atoms encompassing the object, which leaves

the object and enters the eye.’[9]

Aristotle's theory itself is largely based on general

observations, interpreted according to his own philosophical

system. The relation between the eye and the object is not made

clearer by Aristotle's denial of emission from the object. On

the halo and the rainbow, he even adopts a theory, which is

contrary to his own.[10]

The fact is that, while the intromission theory, and its various

versions, seems physically more sound than the emission theory,

it lacks the ability to explain the manifold phenomena presented

by vision.[11]

The emission theory (Euclid and his followers,)

maintains that a ray issues from the eye and proceeds to the

object of vision where its termination constitutes the act of

vision. The idea of

radiation from the eye relies (due to its author (Euclid) on

geometrical explanations for vision. It fails to take

account of physical, physiological and psychological elements

that affect vision. Ptolemy sought to harmonise the geometric

with physical approach. He even carried out some experiments in

support of his views. The problem, as raised by both Omar

and Hill, was that his

experimentation was to support his already preconceived theory,

even manipulating experiments for that purpose,[12]

which is the exact opposite of what experimentation is

supposed to achieve.

Both

intromission and emission theories, thus, suffer from exactly

what Greek science suffers from: its reliance on cogitation and

the lack of experimental foundation.

In

explaining the passage from Greek to Islamic optics, Lindberg,

very ingeniously, subdivides Greek optical theories into five

main strands:

1)

Aristotle's description of light as the actualisation of the

potential transparency of a medium by imposition of a form on

the medium and his intromission theory of vision.

2)

Neoplatonic views on the emanation of power.

3)

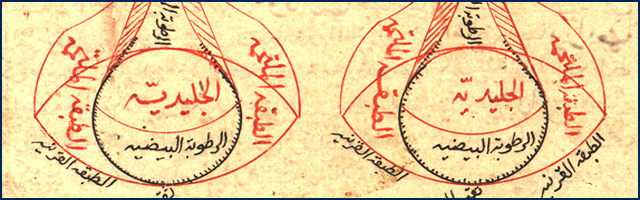

The opinion of Galen and others on the anatomy of the eye and

the physiology of sight.

4)

The intromission theory of the atomists.

5)

The geometrical tradition originated by Euclid and Ptolemy.

It

should be noted, Lindberg adds, that all of these strands,

except perhaps the second, are principally concerned with one

very fundamental question: How do we see? consequently, they

involve questions of a physiological and psychological sort as

well as of physics and mathematics.[13]

[1]

D.C. Lindberg: Studies in the History of Medieval

Optics (London, variorum; 1983).

D.C. Lindberg, Theories of Vision from Al Kindi to

Kepler (Chicago and London, 1976).

-A Catalogue of Medieval and Renaissance Optical

Manuscripts (Toronto; 1975).

[2]

I.e R. Rashed: Le Model de la Sphere transparente et

l'explication de l'arc en ciel: Ibn al-Haytham,

al-Farisi; in

Revue d'Histoire des Sciences;

Vol 23: pp 109-40.

[3]

A. Djebbar: Une Histoire, op cit; p. 268.

[4]

D.R. Hill: Islamic Science, op cit, p 70.

[5]

S.B. Omar

: Ibn al-Haytham's Optics: Bibliotheca Islamica (

[6]

See G.A. Russell: Emergence of Physiological optics, in

the Encyclopaedia (Rashed ed) op cit, pp 672-715;

pp 673-85 in particular.

[7]

D.C. Lindberg: Introduction in Optica Thesaurus:

Alhazen and Witelo; editor: H. Woolf. Johnson

(Reprint Corporation, New York, London, 1972).

D.R. Hill:

Islamic Science, op cit,

pp 70-1.

S.B. Omar

: Ibn al-Haytham's Optics; op cit; p. 17 fwd.

[8]

S.B. Omar

: Ibn al-Haytham’s Optics, op cit; p. 17.

[9]

Ibid; p. 18.

[10]

Ibid; p 19.

[11]

Ibid; p.20.

[12]

D.R. Hill: Islamic Science, op cit, p 71.

[13]

D.C. Lindberg: Introduction in

Optica

op cit;

p. xiv.

|