Muslim Geography: Foundations

Exploring Muslim geography, once more, raises the matter of what

factors were behind the sudden drive for geographical knowledge

in early Islam; amongst such factors, the role of the faith

comes to the fore again as the main and crucial factor. Islam

urged people to open their horizons and know about the wonders

of God’s creation, which acted as a fundamental stimulus for

geographical curiosity.

Journeys were also undertaken to build the records of the

Prophet’s sayings (Hadith

) or

for the purposes of administration and trade, or simply to

satisfy curiosity, to say nothing of pilgrimage.[1]

Hence, roughly, the same combinations of observance of the faith

and practical necessities that account for the rise of other

sciences and aspects of Islamic civilisation. These central

elements are considered in succession, beginning with the direct

role of the faith.

The Islamic Faith and the Rise of Islamic Geography

The

rise of Islamic geography does not owe anything to

Islam, first and foremost, regarded a journey to perform the

pilgrimage rites at Makkah

as a duty incumbent upon

every capable Muslim at least once in a lifetime.[2]

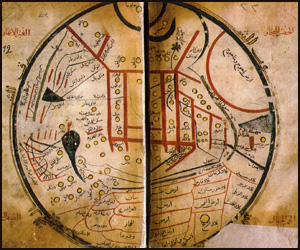

And, thus, whilst nearly all early Muslim geographers included

itineraries to Makkah, or placed it at the centre of their maps

(as will be elaborated upon further on), later geographers used

the same pilgrimage, that on particular occasions, lasted over a

decade, and even twenty five years,[3]

to write most elaborate travel and geographical narratives and

treatises. One amongst such pilgrim-scholars was Mohammed

al-Andalusi

(b. in Ceuta in 1259),

who left for pilgrimage, passing through North Africa

, to

Egypt

,

then Syria

,

and who not only wrote on Tradition

,

but also left two travelogues carrying the appropriate title of

rahalat (travels), where he describes his routes, men of

letters, natural history, etc.[4]

More famed, is the traveller Al-Tidjani, who in the year 1309,

left Tunis

to perform his

pilgrimage, and who wrote on his Rihla.[5]

In this travel, he observed everything he could, providing

information not just about the places he visited, but also about

neighbouring territories, providing geographical and historical

information of the first order, which was vastly used by

subsequent writers, whether Ibn Khaldun

, or

Amari, the latter in his history of Muslim Sicily

,

relying heavily on accounts of al-Tidjani about the island.[6]

The great al-Maqrizi (d. 1442), equally, used the occasion of

his pilgrimage to spend four years in the Hijaz, studying the

routes followed by the pilgrims from southern Arabia

and Abyssinia, and

revising the geographical dictionary of al-Himyari, and that was

years before he wrote his famed Khitat (in 1439), which

remains one of the best works on medieval Egypt.[7]

Pilgrimage

could also be combined

with study and trade, two further powerful elements in

geographical knowledge. Bulliet notes how trade and pilgrimage

could be combined without religious objection, and several years

might be spent making the pilgrimage to Makkah from some distant

location.[8]

Another travel objective was the search for religious knowledge,

particularly in the form of traditional lore (Hadith

).

Indeed, some of the sayings of the Prophet explicitly enjoined

such travels in quest of knowledge, but more important as an

inspiration was the educational stricture, which prevailed

through the 11th century, that valid learning was

dependent upon direct oral transmission.[9]

This requirement of an unbroken chain of oral transmission (isnad)

going back to the Prophet, regarded as the best possible

guarantee of authenticity in this vital area of religious

knowledge, made it necessary for the industrious scholar to

spend months or years travelling from city to city to collect

additional lore.[10]

This developed into a tradition whereby virtually every scholar

of significance travelled extensively at some point in his life[11]

and of course wrote on such travels. Remarkably, this tradition

lasted much beyond the early centuries of Islam. Al-Samani

(1113-1167), for instance, was a 12th century

exegesist and a traditionist, who became well known as a

historian, completing the history of

The

compilation of the Prophet’s sayings also influenced Islamic

geography considerably by imposing the strictest compliance with

accuracy and precision. Kimble thus points out, that it is not

surprising to find Muslim scholars, with all their consideration

for the feelings and traditions of the past, submitting their

authorities to severe critical analysis and revising them where

expedient.[16]

Al-Khwarizmi

(d. 835), for instance,

substantially improved Ptolemy’s geography in his Face of the

Earth, as regards both text and maps.[17]

Staying with religious necessity, Sayili notes how mathematical

or astronomical geography was a very important field of

application for astronomy, and religious needs supplied a strong

motivation for work in this field.[18]

Al-Biruni

thus speaks of the need

for the knowledge of geographical locations in determining the

direction of Makkah

which every Muslim has

to face during the prayers, and he also insists on other

benefits. He says:

‘I

believe that this benefit is not limited to this aspect only of

our divine services but that it extends to other things. For

whosoever determines the longitude and latitude of his country

with precision will thereby be enabled to find out the exact

time of noon and afternoon, and of the end of evening twilight

and of dawn, times which are needed not only in connection with

the prayers but also for fasting, and likewise, he will thereby

be in a position to ascertain the times of the new moon,

although the religious law restricts the determination of this

latter to direct observation because of the Tradition

in which the Prophet

(God Blessing be upon him) said: ‘We are people who do not write

and do not calculate; adding: ‘we indicate the month thus and

thus and thus,’ showing the ten fingers three times, ‘then thus

and thus and thus,’ folding the thumb at the third time.[19]

Moreover the usefulness here exceeds religious matters and

extends to worldly affairs, and what has been mentioned is also

beneficial in finding the correct direction towards one’s

destination and is therefore desirable in that it will bring

good and prevent harm.’[20]

Practical Necessities

The

second element in the rise of Islamic geography, like other

sciences, was practical necessity. Ibn Rusta (fl 903) wrote

Kitab al-A’laq al-Nafisa, the introductory pages of which

are devoted to a detailed discussion of the most essential

fundamental astronomical notions for the solution of

geographical problems such as the size and shape of the earth

and the location of places.[21]

This is followed by the study of geography of

One

of the most elaborate of these works

is Al-Muqaddasi’s (d.1000) Ahsan al-Taqasim, the

first to produce maps in natural colours.[32]

Ahsan at-Taqasim, completed around 985, after preliminary

chapters on general geographical ideas, gives the geographical

arrangement of its different parts of the Islamic world, and an

approximate estimate of the distance from one frontier to the

other.[33]

The countries that are included are Arabia

,

Iraq

and Mesopotamia, Syria

,

Egypt

,

and the Maghrib

(North Africa

),

Spain, into Transoxiana (W. Turkestan), Khurasan, North-West

Iran

(Azerbaijan, Armenia

Transcaucasia), Jibal, Khuzistan (the South-West, ancient Elam

or Susiana), Fars (Persia

),

Kirman and finally Sind (the valley of the Indus).[34]

Each chapter is generally divided into two parts, the first of

which enumerates the different localities and gives good

topographical descriptions, especially of the principal towns,

whilst the second part lists all sorts of subjects which the

author groups under the label of 'particular characteristics.[35]

It looks at towns, their people, the social and ethnic groups,

commerce, natural resources, archaeological monuments,

currencies, the political situation, a vast array of subjects,

which Al-Muqaddasi himself, defines:

‘I

thought it expedient to single out the chorography of the land

of Islam, comprising a description of deserts and seas, lakes

and rivers, famous cities, resting places and the high ways of

commerce, its exports and the staple commodities; an account of

the inhabitants of different countries; of the diversity of

languages and manners of speech; of their dialects and

complexion, their religious tenets; of their measures and

weight, their coins both large and small; with particulars of

their food and drink, their fruits and waters.. the salt lands,

the rocky wastes and sandy deserts, hills, plains and mountains,

the limestone and sandstone; the fat and lean soil, the lands of

plenty and fertility… the industrial arts and literary

avocations.’[36]

There is, thus, no subject of interest to modern geography,

Kramers says, which is not treated by al-Muqaddasi; Miquel, for

his part, praises him as the creator of ‘total geographical

science.'[37]

Devising maps of regions and countries, as will be amply

explored further on, also arose out of practical necessity.

Bagrow notes how itineraries and route maps had to be compiled

for various purposes such as diplomatic missions into distant

lands, such as to

Also

contributing to geographical knowledge was the vast extent of

the

‘Islam has already penetrated from the eastern countries of the

earth to the Western. It spreads westwards to Spain (Andalus),

eastward to the borderland of China

and to the middle of

India

,

southward to Abyssinia and the countries of Zanj (Africa, the

Malay Archipelago and Java), northward to the countries of the

Turks

and Slavs. Thus the

different people are brought together in mutual understanding,

which only God's own Art can bring to pass..¼’[39]

Bulliet notes how Islamic society was a place where long

distance travel was common, an impression supported by the

rarity of historical evidence of political barriers to travel,

even between hostile states, or by efforts of governments to

control the movements of their subjects.[40]

The measure of a prosperous and strong Islamic state, then, was

that the routes were so secure that travellers could move

wherever they wished without molestation.[41]

Trade

Long-distance trade was well established from the very beginning

of Islam, and was encouraged by religious attitudes developed

within the strongly commercial environment of Makkah.[42]

Trade with, and in direction of,

Trade with

There is a very interesting, little known, work by Jitsizo

Kuwabara, dating from 1935, which deals with the Muslim links

with

These trading contacts had dramatic consequences socially, and

also scientifically. On the first front, the Surname of P’u. P’u

is a transliteration of Abu (Abou), a common Arab name; the Sung

Shih records that in the San fo-ch’I country, a large proportion

of the people are surnamed P’u.[73]

Arab traders brought their wives with them, but a few traders

married Chinese women. A record shows that an Arab marrying a

Chinese lady of the imperial family was promoted to high

official position.[74]

Some of the Arabs also studied Chinese culture and language. The

impact on the sciences and the development of navigation was

equally dramatic. The Chinese knew comparatively early the

polarity of the magnetic needle, but it was the Arabs who

applied it to navigation, and the mariner’s compass was brought

back to

Trade was also a fundamental factor behind Islamic writing on

Korea, and a good number of Muslim geographers wrote on Korea

between the 9th and 15th century, and were

studied by Kei Won Chung and Hourani.[76]

The Muslims used the name al-Shila or al-Sila, after an early

dynasty which ruled there until 935 to refer to

Diplomacy and Politics

Diplomacy and politics, finally, also stimulated geographical

knowledge, a well known instance being that of Ibn Fadlan’s

travels to

In

the year 965, two embassies were sent by Muslim rulers of North

Africa

and Muslim Spain to the

In

the far eastern parts of Islam, Abu Dulaf (born in Yambo, near

Makkah

)

(fl early 10th century) spent his career in

Al-Biruni

,

who spent much of his working life in the court of the Sultan

Mahmud of Ghazna (11th century), accompanied him in

his expedition to

[1]

G.H. T. Kimble: Geography in the Middle Ages

(Methuen &Co Ltd; London; 1938), pp. 48-9.

[2]

R. Bulliet: Travel

and Transport;

Dictionary of the Middle Ages; op cit; vol 12;

pp. 147-8;

p. 147.

[3]

Ibn Jubayr

, for instance, wrote his narratives of travel on the

pilgrimage to Makkah

, which he undertook to expiate a sin (drinking wine).

Ibn Jubayr: Voyages, tr. with notes by M.

Gaudefroy Demombynes (Paris, 1949-65).

Ibn Battuta

also left his

hometown of Tangiers with the intention of pilgrimage to

Makkah

, which he accomplished five times, and all the

adventures in between, he relates in his work. Ibn

Battuta: Travels in Asia and Africa; trans and

selected by H.A.R. Gibb;

Routledge;

[4]

I.J. Krckovskij: Izbrannye Socinenja;. Pp. 382-3.

[5]

H. H. Abd-al-Wahab: Rihlat al-Tijani;

[6]

I.J. Krckovskij: Izbrannye Socinenja;. Pp. 383-4.

[7]

Ibid. pp. 525-6.

[8]

R. Bulliet: Travel

and Transport;

op cit; p. 147.

[9]

Ibid.

[10]

Ibid.

[11]

Ibid.

[12]

I.J. Krckovskij: Izbrannye Socinenja. op cit; pp.

319-20.

[13]

I.J. Krckovskij: Izbrannye Socinenja; 319-20. See

also S.M. Ahmad: History; op cit; p. 179.

[14]

I.J. Krckovskij: Izbrannye Socinenja; 319-20.

[15]

I.J. Krckovskij: Izbrannye Socinenja; 319-20. See

also S.M. Ahmad: History; p. 179.

[16]

G.H. T. Kimble: Geography; op cit; pp. 48-9.

[17]

This work was accompanied by a map of the world executed

by al-Khwarizmi and sixty nine other scholars at the

instigation of Al-Mamun; in G.T. Kimble: Geography;

Note 1; p. 49.

[18]

A. Sayili: The Observatory

; op cit; p. 24.

[19]

See Bukhari: Sahih; Book 30 (on fasting) section 13. and

Muslim: Sahih; Book 13; tradition 15.

[20]

Al-Biruni

: Tahdid al-Amaqin; op cit; pp. 323-4.

[21]

Ibn Rusta: Kitab al-A’laq al-nafisa; ed De Goeje

(Leyden; 1892), vol vii.

[22]

Ibid.

[23]

Texts and translations: First edition with French

translation and notes by C. Barbier de Meynard: le Livre

des routes et des provinces; Journal Asiatique,

vol 5, 1-127, 227-95, 446-532, (1865).

A better text has been published by M.J. de Goeje, with

French translation and notes: Bibliotheca

geographorum arabicorum, 6 (

[24]

G.R. Tibbetts: The Balkhi School of Geographers in

History of Cartography (Harley-Woodward ed); op cit;

pp. 108-29; at pp. 117.

[25]

Al-Ya'qubi: Les pays, tr.

G. Wiet (

[26]

G.R. Tibbetts: The Balkhi School of Geographers; op cit;

p. 117.

[27]

Carra de Vaux: Les Penseurs, op cit, p. 3.

[28]

G.R. Tibbetts: The Balkhi School of Geographers; op cit;

pp. 116-7.

[29]

Ibid; p. 117.

[30]

Al-Muqaddasi:

Ahsan at-taqasim fi Ma'rifat al-Aqalim;

M.J. de Goeje ed., Bibliotheca Geographorum

Arabicum, 2nd edition., III vols (

[31]

C. de Vaux: Les Penseurs; op cit, pp 27-8.

[32]Al-Muqaddasi:

Ahsan at-taqasim;

op cit.

[33]

D.M. Dunlop: Arab Civilisation 800-1500 A.D

(Longman Group Ltd, 1971), p. 166.

[34]

Ibid.

[35]

Ibid.

[36]

Al-Muqaddasi: Ahsan al-Taqasim; op cit; pp. 1-2.

[37]

In D.M. Dunlop: Arab Civilisation; op cit; p.

166.

[38]

L. Bagrow: History of Cartography; Revised and

Enlarged by R.A. Skelton (C. Watts and Co Ltd; London;

1964), p. 54.

[39]

In

The Book of the Demarkation of the Limits of the

Areas

In N. Ahmad, Muslim Contribution to Geography

(Lahore: M. Ashraf, 1947), p 35.

[40]

R. Bulliet: Travel

and Transport,

op cit; pp.

147-8.

[41]

Ibid.

[42]

Ibid; p. 147.

[43]

Relations des Voyages faites par les

Arabes et les Persans dans l'Inde et a la Chine,

ed. et tr.

Langles et Reinaud, 2 vols (Imprimerie Royale; Paris;

1845).

[44]

G. Sarton: Introduction; op cit; vol 1; p.636.

[45]

Edited by Reinaud (

[46]

S.M.Z. Alavi: Arab Geography (The Department of

Geography; Aligarh; 1965), p. 33.

[47]

In Carra de Vaux: Les Penseurs de l’Islam;

op cit; pp. 53-9.

[48]

S.M.Z. Alavi: Arab Geography; op cit; p. 33.

[49]

A.S.S. Nadvi: Arab Navigation

(S. M. Ashraf

Publishers; Lahore; 1966), pp. 55-8.

[50]

Ibid.

[51]

Ibid; p. 52.

[52]

J.H. Kramers: Geography and Commerce, in The Legacy

of Islam (edited by T. Arnold and A. Guillaume,) op

cit; pp 79-107; at p. 95.

[53]

Carra de Vaux: Les Penseurs; op cit; at pp. 55-6.

[54]

Ibid, p.

58.

[55]

Sulaiman: Silsilat al-Tawarikh; Ed Reinaud (

[56]

Ibid; p. 41.

[57]

Ibid; pp. 11-2.

[58]

Carra de Vaux: Les Penseurs; op cit;

pp. 57-8.

[59]

The Kitab al-buldan appears in M. J. de Goeje,

ed., Bibliotheca ceocraphorum

arabicorum,

Vll (1892);

Ed and tr into French by G Wiet: Les Pays (1937).

[60]

L.I. Conrad: Al-Yaqubi; Dictionary of the Middle

Ages; op cit; vol 12; pp. 717-8; at p. 718.

[61]

Ibid.

[62]

G. Ferrand: Relations de Voyages et textes

geographiques

Arabes, Persans and Turks

relatifs a

l’Extreme orient du VIIem au XVIIIem Siecles;

E. Leroux, Paris, 1913-4.

Extracts above are from the re-edition by F. Sezgin of

Ferrand’s work (

[63]

Kitab al-boldan auctore Ibn al-Faqih

al-Hamadhani; edited by M. J. De Goeje; Bibliotheca

geographorum arabicorum, 5 (

[64]

G. Sarton: Introduction; op cit; vol 1; p.635.

[65]

G. Ferrand: Relations de Voyages; op cit; pp. 54-66..

[66]

Ibid; p.118 ff.

[67]

Ibid;

p.130 ff.

[68]

Ibid; pp 302-4.

[69]

Jitsizo Kuwabara: To so jidai ni okeru Arab-jin no

Shina Tsuho no gaiko; kotomi So matsu no Teikyo-shihaku

Saiiki-jin Ho Ju-ko no jiseki (Piu Shou-Keng, a man

of the Western regions, who was superintendent of the

Trading Ships’ office in Chiuan-chou towards the end of

the Sung dynasty, together with a general sketch of

trade of the Arabs in China

during the T’Ang

and Sung eras) Tokyo; Iwanami; 1935. Reviewed by Shio

Sakanishi;

[70]

Ibid; P. 121.

[71]

Ibid.

[72]

Ibid; p. 120.

[73]

Ibid.

[74]

Ibid; p. 120.

[75]

Ibid.

[76]

Kei Won Chung; G.F. Hourani: Arab Geographers of Korea;

Journal of the American Oriental

Society;

vol 58; pp. 658-61.

[77]

Ibid; 658.

[78]

Ibid; 658-60.

[79]

Chosen Yuska;

[80]

Ibid.

[81]

Yi Neung Wha: History of Korean Buddhism (

[82]

W.E.D. Allen: The Poet and the Spae-wife: An Attempt to

Reconstruct Al-Ghazal's Embassy to the Vikings (1960),

in Viking Society for Northern Research,

Saga-Book, 15 (1960).

[83]

W.E.D. Allen: The Poet and the Spae-wife: pp. 1-14. See

also S.M. Ahmad: A History; op cit; p.39.

[84]

Ibid.

[85]

Ibid.

[86]

See Harris Birkeland: Nordens hidstorie I

middelalderen etter arabiskenkilder, Norske

Videnskaps-Akademi i

[87]

I.J. Krckovskij: Izbrannye Socinenja,. Op cit;

pp. 190-2;

S.M. Ahmad: History; op cit; p. 116.

[88]

I.J. Krckovskij: Izbrannye Socinenja,. Op cit;

pp. 190-2; S.M. Ahmad: History; op cit; p. 116.

[89]

G. Sarton: Introduction; op cit; vol 1; p. 637.

[90]

Ibid.

[91]

Ibid.

[92]

G. Le Bon: La Civilisation; op cit;

p.370. |